The team behind Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald throws an awful lot at the screen during this clotted two-hour-plus diversion, the latest instalment in the J.K. Rowling-verse. As is often the case in a Rowling production, evil is ascendant, seeping through both human and magic realms like poison gas.

Mostly, though, because Rowling builds worlds, what Grindelwald has is a great deal of story. The movie is chockablock with stuff: titular creatures (if not nearly enough), attractive people, scampering extras, eye-catching locations, tragic flashbacks, teary confessions and largely bloodless, spectacular violence. It’s an embarrassment of riches, and it’s suffocating.

This is the second movie in what promises (threatens!) to be an extended Fantastic Beasts franchise. (Rowling spun this series out of the Harry Potter cycle, so subfranchise might be more correct.) It centres on Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a “magizoologist” who studies, rescues and nurses magical critters. Unlike Harry’s tale, though, Newt’s story opens with him already of age. The new movie picks up in New York in the mid-1920s, the end point of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. With its cloche hats, Model T’s, Art Deco flourishes and a Jazz Age vibe, it is a handsomely designed change of scenery from Potter World, one that’s mostly a story delivery system.

Not much has happened since the last movie; mostly, people and parts have been shifted in preparation for the next great narrative heave forward. Once again, Newt is scurrying about while nefarious doings unfold in separate story lines. One is dominated by Gellert Grindelwald (a perfectly unmemorable Johnny Depp), an evil wizard who looks like he’s been dipped in flour (and who last appeared in the more flattering form of Colin Farrell). Grindelwald is consolidating his power and has big plans. These have become more transparent as fascism has seeped into the story, totalitarianism’s threat increasingly giving dark meaning to all the violence and ugly phrases like “pure blood.”

Rowling is a literary magpie and first-rate synthesiser, and her stated inspirations for the Harry Potter books range from classical mythology to Jane Austen. Traces of the Bible, Shakespeare, Tolkien and other Western-lit staples are sprinkled throughout that series and therefore this one, too. However intentional, they form part of a cultural database, which is as smart as it is appealing. (The influences flatter but don’t overwhelm readers, and offer different interpretive portals into the tale.) Given some of these influences, it’s no surprise that the series is touched by death; given the arc of history, it’s also no surprise that it has morphed into an apocalyptic war story.

A bleak, violent end — and the intimation of a worldwide cataclysm — looms from the very first scene of The Crimes of Grindelwald. Directed by David Yates and written by Rowling, the movie opens with a fierce, visually chaotic prison break that springs Grindelwald and sets the angry mood. The bad times rush in along with the assorted villains bringing escalating violence. By the time Newt materialises with his magical suitcase, where he often keeps his roaring, scuttling menagerie (mostly, sometimes) contained, the movie already seems like a series finale. It’s so freighted with foreboding that even the would-be whimsy feels leaden.

The darkness makes a startling contrast to the first movie, which mostly involved a lot of narrative place setting, including all the fun beastly introductions. Most of the characters are back, including Tina (Katherine Waterston), a law-and-order type called an Auror and Newt’s limp romantic foil. One of the disappointments of the Fantastic Beasts movies has been the casting, which has little of the wit and powerhouse talent that shored up the Harry Potter series. Redmayne can be a sensitive presence, but when he isn’t well directed his fluttering and darting looks quickly settle into ingratiating shtick. If Newt has any depth, a mewling, quivering Redmayne seems unlikely to tap it.

That the contents of Newt’s suitcase are consistently more interesting than he is remains a problem, too. Rowling keeps trying to make him and the mysterious Credence (Ezra Miller) the narrative’s twinned centre. Yet your attention keeps returning, almost longingly, to the movie’s funnier, more charming supporting players, notably Queenie (a delightful Alison Sudol) and Jacob (the equally appealing Dan Fogler). They don’t share Newt’s pedigree or Credence’s ominous threat; they’re side dishes. But they have the charming idiosyncrasies and human frailties of Rowling’s best creations, and they prove to be the ones you care most about.

On the page, Rowling is a master storyteller, creating worlds so richly populated and densely textured that you can easily summon them up in your mind without ever having watched a single adaptation of her work. What occasionally trips her up is plot structure — the arrangement of all her attractive, whirling parts. Steve Kloves, who wrote all but one of the Harry Potter movies, was gifted at giving cinematic shape to Rowling’s increasingly long novels, with all their detours and savoury details. Here, however, Rowling has surrendered to her maximalist tendencies and so cluttered up the story that you spend far too much time trying to untangle who did what to whom and why.

Its pedigree and behind-the-scenes talent ensure that The Crimes of Grindelwald is scattered with minor pleasures, mostly ornamental — the brassy filigree that summons up old worlds, the stray elf that reminds you of adventures past. There’s also the Zouwu, a charming monster with a catlike face and a long body that whips around like a Chinese New Year dragon, upstaging everyone who shares the screen with it. Yet, by the time Rowling has gathered all her story lines together and a somnolent Zoe Kravitz, as the slinky Leta Lestrange, is guiding you through another digression, the movie has loosened its grip on you. That tightens only when the story tantalisingly shifts to Hogwarts, where Dumbledore, fond memories and the promise of better stories await.

The team behind Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald throws an awful lot at the screen during this clotted two-hour-plus diversion, the latest instalment in the J.K. Rowling-verse. As is often the case in a Rowling production, evil is ascendant, seeping through both human and magic realms like poison gas.

Mostly, though, because Rowling builds worlds, what Grindelwald has is a great deal of story. The movie is chockablock with stuff: titular creatures (if not nearly enough), attractive people, scampering extras, eye-catching locations, tragic flashbacks, teary confessions and largely bloodless, spectacular violence. It’s an embarrassment of riches, and it’s suffocating.

This is the second movie in what promises (threatens!) to be an extended Fantastic Beasts franchise. (Rowling spun this series out of the Harry Potter cycle, so subfranchise might be more correct.) It centres on Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a “magizoologist” who studies, rescues and nurses magical critters. Unlike Harry’s tale, though, Newt’s story opens with him already of age. The new movie picks up in New York in the mid-1920s, the end point of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. With its cloche hats, Model T’s, Art Deco flourishes and a Jazz Age vibe, it is a handsomely designed change of scenery from Potter World, one that’s mostly a story delivery system.

Not much has happened since the last movie; mostly, people and parts have been shifted in preparation for the next great narrative heave forward. Once again, Newt is scurrying about while nefarious doings unfold in separate story lines. One is dominated by Gellert Grindelwald (a perfectly unmemorable Johnny Depp), an evil wizard who looks like he’s been dipped in flour (and who last appeared in the more flattering form of Colin Farrell). Grindelwald is consolidating his power and has big plans. These have become more transparent as fascism has seeped into the story, totalitarianism’s threat increasingly giving dark meaning to all the violence and ugly phrases like “pure blood.”

Rowling is a literary magpie and first-rate synthesiser, and her stated inspirations for the Harry Potter books range from classical mythology to Jane Austen. Traces of the Bible, Shakespeare, Tolkien and other Western-lit staples are sprinkled throughout that series and therefore this one, too. However intentional, they form part of a cultural database, which is as smart as it is appealing. (The influences flatter but don’t overwhelm readers, and offer different interpretive portals into the tale.) Given some of these influences, it’s no surprise that the series is touched by death; given the arc of history, it’s also no surprise that it has morphed into an apocalyptic war story.

A bleak, violent end — and the intimation of a worldwide cataclysm — looms from the very first scene of The Crimes of Grindelwald. Directed by David Yates and written by Rowling, the movie opens with a fierce, visually chaotic prison break that springs Grindelwald and sets the angry mood. The bad times rush in along with the assorted villains bringing escalating violence. By the time Newt materialises with his magical suitcase, where he often keeps his roaring, scuttling menagerie (mostly, sometimes) contained, the movie already seems like a series finale. It’s so freighted with foreboding that even the would-be whimsy feels leaden.

The darkness makes a startling contrast to the first movie, which mostly involved a lot of narrative place setting, including all the fun beastly introductions. Most of the characters are back, including Tina (Katherine Waterston), a law-and-order type called an Auror and Newt’s limp romantic foil. One of the disappointments of the Fantastic Beasts movies has been the casting, which has little of the wit and powerhouse talent that shored up the Harry Potter series. Redmayne can be a sensitive presence, but when he isn’t well directed his fluttering and darting looks quickly settle into ingratiating shtick. If Newt has any depth, a mewling, quivering Redmayne seems unlikely to tap it.

That the contents of Newt’s suitcase are consistently more interesting than he is remains a problem, too. Rowling keeps trying to make him and the mysterious Credence (Ezra Miller) the narrative’s twinned centre. Yet your attention keeps returning, almost longingly, to the movie’s funnier, more charming supporting players, notably Queenie (a delightful Alison Sudol) and Jacob (the equally appealing Dan Fogler). They don’t share Newt’s pedigree or Credence’s ominous threat; they’re side dishes. But they have the charming idiosyncrasies and human frailties of Rowling’s best creations, and they prove to be the ones you care most about.

On the page, Rowling is a master storyteller, creating worlds so richly populated and densely textured that you can easily summon them up in your mind without ever having watched a single adaptation of her work. What occasionally trips her up is plot structure — the arrangement of all her attractive, whirling parts. Steve Kloves, who wrote all but one of the Harry Potter movies, was gifted at giving cinematic shape to Rowling’s increasingly long novels, with all their detours and savoury details. Here, however, Rowling has surrendered to her maximalist tendencies and so cluttered up the story that you spend far too much time trying to untangle who did what to whom and why.

Its pedigree and behind-the-scenes talent ensure that The Crimes of Grindelwald is scattered with minor pleasures, mostly ornamental — the brassy filigree that summons up old worlds, the stray elf that reminds you of adventures past. There’s also the Zouwu, a charming monster with a catlike face and a long body that whips around like a Chinese New Year dragon, upstaging everyone who shares the screen with it. Yet, by the time Rowling has gathered all her story lines together and a somnolent Zoe Kravitz, as the slinky Leta Lestrange, is guiding you through another digression, the movie has loosened its grip on you. That tightens only when the story tantalisingly shifts to Hogwarts, where Dumbledore, fond memories and the promise of better stories await.

The team behind Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald throws an awful lot at the screen during this clotted two-hour-plus diversion, the latest instalment in the J.K. Rowling-verse. As is often the case in a Rowling production, evil is ascendant, seeping through both human and magic realms like poison gas.

Mostly, though, because Rowling builds worlds, what Grindelwald has is a great deal of story. The movie is chockablock with stuff: titular creatures (if not nearly enough), attractive people, scampering extras, eye-catching locations, tragic flashbacks, teary confessions and largely bloodless, spectacular violence. It’s an embarrassment of riches, and it’s suffocating.

This is the second movie in what promises (threatens!) to be an extended Fantastic Beasts franchise. (Rowling spun this series out of the Harry Potter cycle, so subfranchise might be more correct.) It centres on Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a “magizoologist” who studies, rescues and nurses magical critters. Unlike Harry’s tale, though, Newt’s story opens with him already of age. The new movie picks up in New York in the mid-1920s, the end point of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. With its cloche hats, Model T’s, Art Deco flourishes and a Jazz Age vibe, it is a handsomely designed change of scenery from Potter World, one that’s mostly a story delivery system.

Not much has happened since the last movie; mostly, people and parts have been shifted in preparation for the next great narrative heave forward. Once again, Newt is scurrying about while nefarious doings unfold in separate story lines. One is dominated by Gellert Grindelwald (a perfectly unmemorable Johnny Depp), an evil wizard who looks like he’s been dipped in flour (and who last appeared in the more flattering form of Colin Farrell). Grindelwald is consolidating his power and has big plans. These have become more transparent as fascism has seeped into the story, totalitarianism’s threat increasingly giving dark meaning to all the violence and ugly phrases like “pure blood.”

Rowling is a literary magpie and first-rate synthesiser, and her stated inspirations for the Harry Potter books range from classical mythology to Jane Austen. Traces of the Bible, Shakespeare, Tolkien and other Western-lit staples are sprinkled throughout that series and therefore this one, too. However intentional, they form part of a cultural database, which is as smart as it is appealing. (The influences flatter but don’t overwhelm readers, and offer different interpretive portals into the tale.) Given some of these influences, it’s no surprise that the series is touched by death; given the arc of history, it’s also no surprise that it has morphed into an apocalyptic war story.

A bleak, violent end — and the intimation of a worldwide cataclysm — looms from the very first scene of The Crimes of Grindelwald. Directed by David Yates and written by Rowling, the movie opens with a fierce, visually chaotic prison break that springs Grindelwald and sets the angry mood. The bad times rush in along with the assorted villains bringing escalating violence. By the time Newt materialises with his magical suitcase, where he often keeps his roaring, scuttling menagerie (mostly, sometimes) contained, the movie already seems like a series finale. It’s so freighted with foreboding that even the would-be whimsy feels leaden.

The darkness makes a startling contrast to the first movie, which mostly involved a lot of narrative place setting, including all the fun beastly introductions. Most of the characters are back, including Tina (Katherine Waterston), a law-and-order type called an Auror and Newt’s limp romantic foil. One of the disappointments of the Fantastic Beasts movies has been the casting, which has little of the wit and powerhouse talent that shored up the Harry Potter series. Redmayne can be a sensitive presence, but when he isn’t well directed his fluttering and darting looks quickly settle into ingratiating shtick. If Newt has any depth, a mewling, quivering Redmayne seems unlikely to tap it.

That the contents of Newt’s suitcase are consistently more interesting than he is remains a problem, too. Rowling keeps trying to make him and the mysterious Credence (Ezra Miller) the narrative’s twinned centre. Yet your attention keeps returning, almost longingly, to the movie’s funnier, more charming supporting players, notably Queenie (a delightful Alison Sudol) and Jacob (the equally appealing Dan Fogler). They don’t share Newt’s pedigree or Credence’s ominous threat; they’re side dishes. But they have the charming idiosyncrasies and human frailties of Rowling’s best creations, and they prove to be the ones you care most about.

On the page, Rowling is a master storyteller, creating worlds so richly populated and densely textured that you can easily summon them up in your mind without ever having watched a single adaptation of her work. What occasionally trips her up is plot structure — the arrangement of all her attractive, whirling parts. Steve Kloves, who wrote all but one of the Harry Potter movies, was gifted at giving cinematic shape to Rowling’s increasingly long novels, with all their detours and savoury details. Here, however, Rowling has surrendered to her maximalist tendencies and so cluttered up the story that you spend far too much time trying to untangle who did what to whom and why.

Its pedigree and behind-the-scenes talent ensure that The Crimes of Grindelwald is scattered with minor pleasures, mostly ornamental — the brassy filigree that summons up old worlds, the stray elf that reminds you of adventures past. There’s also the Zouwu, a charming monster with a catlike face and a long body that whips around like a Chinese New Year dragon, upstaging everyone who shares the screen with it. Yet, by the time Rowling has gathered all her story lines together and a somnolent Zoe Kravitz, as the slinky Leta Lestrange, is guiding you through another digression, the movie has loosened its grip on you. That tightens only when the story tantalisingly shifts to Hogwarts, where Dumbledore, fond memories and the promise of better stories await.

The team behind Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald throws an awful lot at the screen during this clotted two-hour-plus diversion, the latest instalment in the J.K. Rowling-verse. As is often the case in a Rowling production, evil is ascendant, seeping through both human and magic realms like poison gas.

Mostly, though, because Rowling builds worlds, what Grindelwald has is a great deal of story. The movie is chockablock with stuff: titular creatures (if not nearly enough), attractive people, scampering extras, eye-catching locations, tragic flashbacks, teary confessions and largely bloodless, spectacular violence. It’s an embarrassment of riches, and it’s suffocating.

This is the second movie in what promises (threatens!) to be an extended Fantastic Beasts franchise. (Rowling spun this series out of the Harry Potter cycle, so subfranchise might be more correct.) It centres on Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a “magizoologist” who studies, rescues and nurses magical critters. Unlike Harry’s tale, though, Newt’s story opens with him already of age. The new movie picks up in New York in the mid-1920s, the end point of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. With its cloche hats, Model T’s, Art Deco flourishes and a Jazz Age vibe, it is a handsomely designed change of scenery from Potter World, one that’s mostly a story delivery system.

Not much has happened since the last movie; mostly, people and parts have been shifted in preparation for the next great narrative heave forward. Once again, Newt is scurrying about while nefarious doings unfold in separate story lines. One is dominated by Gellert Grindelwald (a perfectly unmemorable Johnny Depp), an evil wizard who looks like he’s been dipped in flour (and who last appeared in the more flattering form of Colin Farrell). Grindelwald is consolidating his power and has big plans. These have become more transparent as fascism has seeped into the story, totalitarianism’s threat increasingly giving dark meaning to all the violence and ugly phrases like “pure blood.”

Rowling is a literary magpie and first-rate synthesiser, and her stated inspirations for the Harry Potter books range from classical mythology to Jane Austen. Traces of the Bible, Shakespeare, Tolkien and other Western-lit staples are sprinkled throughout that series and therefore this one, too. However intentional, they form part of a cultural database, which is as smart as it is appealing. (The influences flatter but don’t overwhelm readers, and offer different interpretive portals into the tale.) Given some of these influences, it’s no surprise that the series is touched by death; given the arc of history, it’s also no surprise that it has morphed into an apocalyptic war story.

A bleak, violent end — and the intimation of a worldwide cataclysm — looms from the very first scene of The Crimes of Grindelwald. Directed by David Yates and written by Rowling, the movie opens with a fierce, visually chaotic prison break that springs Grindelwald and sets the angry mood. The bad times rush in along with the assorted villains bringing escalating violence. By the time Newt materialises with his magical suitcase, where he often keeps his roaring, scuttling menagerie (mostly, sometimes) contained, the movie already seems like a series finale. It’s so freighted with foreboding that even the would-be whimsy feels leaden.

The darkness makes a startling contrast to the first movie, which mostly involved a lot of narrative place setting, including all the fun beastly introductions. Most of the characters are back, including Tina (Katherine Waterston), a law-and-order type called an Auror and Newt’s limp romantic foil. One of the disappointments of the Fantastic Beasts movies has been the casting, which has little of the wit and powerhouse talent that shored up the Harry Potter series. Redmayne can be a sensitive presence, but when he isn’t well directed his fluttering and darting looks quickly settle into ingratiating shtick. If Newt has any depth, a mewling, quivering Redmayne seems unlikely to tap it.

That the contents of Newt’s suitcase are consistently more interesting than he is remains a problem, too. Rowling keeps trying to make him and the mysterious Credence (Ezra Miller) the narrative’s twinned centre. Yet your attention keeps returning, almost longingly, to the movie’s funnier, more charming supporting players, notably Queenie (a delightful Alison Sudol) and Jacob (the equally appealing Dan Fogler). They don’t share Newt’s pedigree or Credence’s ominous threat; they’re side dishes. But they have the charming idiosyncrasies and human frailties of Rowling’s best creations, and they prove to be the ones you care most about.

On the page, Rowling is a master storyteller, creating worlds so richly populated and densely textured that you can easily summon them up in your mind without ever having watched a single adaptation of her work. What occasionally trips her up is plot structure — the arrangement of all her attractive, whirling parts. Steve Kloves, who wrote all but one of the Harry Potter movies, was gifted at giving cinematic shape to Rowling’s increasingly long novels, with all their detours and savoury details. Here, however, Rowling has surrendered to her maximalist tendencies and so cluttered up the story that you spend far too much time trying to untangle who did what to whom and why.

Its pedigree and behind-the-scenes talent ensure that The Crimes of Grindelwald is scattered with minor pleasures, mostly ornamental — the brassy filigree that summons up old worlds, the stray elf that reminds you of adventures past. There’s also the Zouwu, a charming monster with a catlike face and a long body that whips around like a Chinese New Year dragon, upstaging everyone who shares the screen with it. Yet, by the time Rowling has gathered all her story lines together and a somnolent Zoe Kravitz, as the slinky Leta Lestrange, is guiding you through another digression, the movie has loosened its grip on you. That tightens only when the story tantalisingly shifts to Hogwarts, where Dumbledore, fond memories and the promise of better stories await.

The team behind Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald throws an awful lot at the screen during this clotted two-hour-plus diversion, the latest instalment in the J.K. Rowling-verse. As is often the case in a Rowling production, evil is ascendant, seeping through both human and magic realms like poison gas.

Mostly, though, because Rowling builds worlds, what Grindelwald has is a great deal of story. The movie is chockablock with stuff: titular creatures (if not nearly enough), attractive people, scampering extras, eye-catching locations, tragic flashbacks, teary confessions and largely bloodless, spectacular violence. It’s an embarrassment of riches, and it’s suffocating.

This is the second movie in what promises (threatens!) to be an extended Fantastic Beasts franchise. (Rowling spun this series out of the Harry Potter cycle, so subfranchise might be more correct.) It centres on Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), a “magizoologist” who studies, rescues and nurses magical critters. Unlike Harry’s tale, though, Newt’s story opens with him already of age. The new movie picks up in New York in the mid-1920s, the end point of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. With its cloche hats, Model T’s, Art Deco flourishes and a Jazz Age vibe, it is a handsomely designed change of scenery from Potter World, one that’s mostly a story delivery system.

Not much has happened since the last movie; mostly, people and parts have been shifted in preparation for the next great narrative heave forward. Once again, Newt is scurrying about while nefarious doings unfold in separate story lines. One is dominated by Gellert Grindelwald (a perfectly unmemorable Johnny Depp), an evil wizard who looks like he’s been dipped in flour (and who last appeared in the more flattering form of Colin Farrell). Grindelwald is consolidating his power and has big plans. These have become more transparent as fascism has seeped into the story, totalitarianism’s threat increasingly giving dark meaning to all the violence and ugly phrases like “pure blood.”

Rowling is a literary magpie and first-rate synthesiser, and her stated inspirations for the Harry Potter books range from classical mythology to Jane Austen. Traces of the Bible, Shakespeare, Tolkien and other Western-lit staples are sprinkled throughout that series and therefore this one, too. However intentional, they form part of a cultural database, which is as smart as it is appealing. (The influences flatter but don’t overwhelm readers, and offer different interpretive portals into the tale.) Given some of these influences, it’s no surprise that the series is touched by death; given the arc of history, it’s also no surprise that it has morphed into an apocalyptic war story.

A bleak, violent end — and the intimation of a worldwide cataclysm — looms from the very first scene of The Crimes of Grindelwald. Directed by David Yates and written by Rowling, the movie opens with a fierce, visually chaotic prison break that springs Grindelwald and sets the angry mood. The bad times rush in along with the assorted villains bringing escalating violence. By the time Newt materialises with his magical suitcase, where he often keeps his roaring, scuttling menagerie (mostly, sometimes) contained, the movie already seems like a series finale. It’s so freighted with foreboding that even the would-be whimsy feels leaden.

The darkness makes a startling contrast to the first movie, which mostly involved a lot of narrative place setting, including all the fun beastly introductions. Most of the characters are back, including Tina (Katherine Waterston), a law-and-order type called an Auror and Newt’s limp romantic foil. One of the disappointments of the Fantastic Beasts movies has been the casting, which has little of the wit and powerhouse talent that shored up the Harry Potter series. Redmayne can be a sensitive presence, but when he isn’t well directed his fluttering and darting looks quickly settle into ingratiating shtick. If Newt has any depth, a mewling, quivering Redmayne seems unlikely to tap it.

That the contents of Newt’s suitcase are consistently more interesting than he is remains a problem, too. Rowling keeps trying to make him and the mysterious Credence (Ezra Miller) the narrative’s twinned centre. Yet your attention keeps returning, almost longingly, to the movie’s funnier, more charming supporting players, notably Queenie (a delightful Alison Sudol) and Jacob (the equally appealing Dan Fogler). They don’t share Newt’s pedigree or Credence’s ominous threat; they’re side dishes. But they have the charming idiosyncrasies and human frailties of Rowling’s best creations, and they prove to be the ones you care most about.

On the page, Rowling is a master storyteller, creating worlds so richly populated and densely textured that you can easily summon them up in your mind without ever having watched a single adaptation of her work. What occasionally trips her up is plot structure — the arrangement of all her attractive, whirling parts. Steve Kloves, who wrote all but one of the Harry Potter movies, was gifted at giving cinematic shape to Rowling’s increasingly long novels, with all their detours and savoury details. Here, however, Rowling has surrendered to her maximalist tendencies and so cluttered up the story that you spend far too much time trying to untangle who did what to whom and why.

Its pedigree and behind-the-scenes talent ensure that The Crimes of Grindelwald is scattered with minor pleasures, mostly ornamental — the brassy filigree that summons up old worlds, the stray elf that reminds you of adventures past. There’s also the Zouwu, a charming monster with a catlike face and a long body that whips around like a Chinese New Year dragon, upstaging everyone who shares the screen with it. Yet, by the time Rowling has gathered all her story lines together and a somnolent Zoe Kravitz, as the slinky Leta Lestrange, is guiding you through another digression, the movie has loosened its grip on you. That tightens only when the story tantalisingly shifts to Hogwarts, where Dumbledore, fond memories and the promise of better stories await.

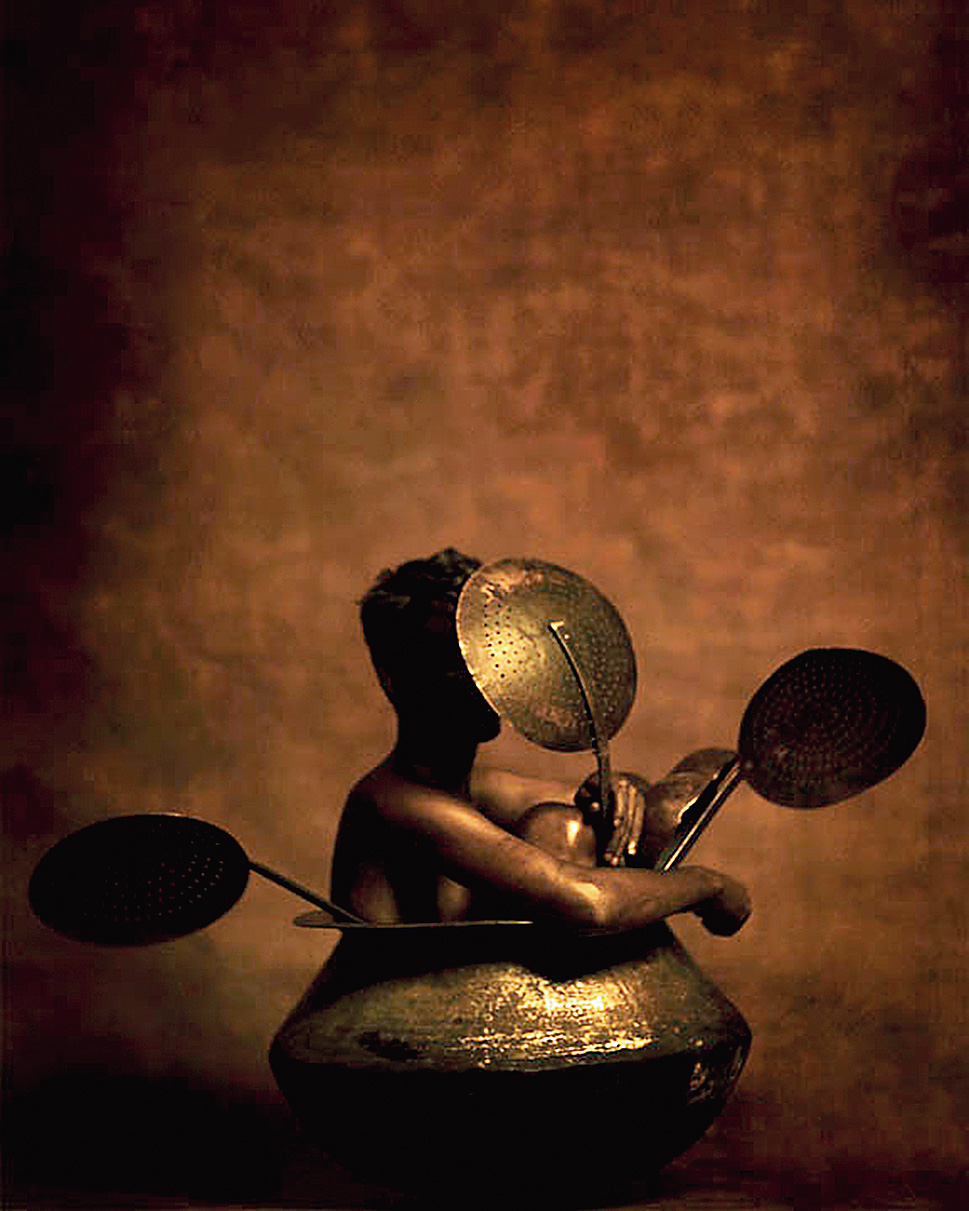

For scenographer Swarup Dutta, questions on identity were a natural reaction to his socio-political being, with about 20 years in the arts, be it fashion, design, scenography or teaching. Therefore, the nomenclature of his first solo exhibition expressing this interrogation of identities titled ‘Kaw’ is no surprise — he is a Bengali artist living and working in Calcutta and seeking answers to questions like ki? (what), ke? (who), keno? (why), kokhon? (when), kothay? (where) and ki bhabey? (how), which all begin with the Bengali letter ‘kaw’.

When we entered the quaint gallery space of Akar Prakar at Hindustan Park earlier this week, Swarup was busy setting up the images, meting out framing advice to his volunteers. “It’s a little crazy now with only days to go for the November 16 opening but I am excited,” he said before taking us through his works. A chat...

For scenographer Swarup Dutta, questions on identity were a natural reaction to his socio-political being, with about 20 years in the arts, be it fashion, design, scenography or teaching. Therefore, the nomenclature of his first solo exhibition expressing this interrogation of identities titled ‘Kaw’ is no surprise — he is a Bengali artist living and working in Calcutta and seeking answers to questions like ki? (what), ke? (who), keno? (why), kokhon? (when), kothay? (where) and ki bhabey? (how), which all begin with the Bengali letter ‘kaw’.

When we entered the quaint gallery space of Akar Prakar at Hindustan Park earlier this week, Swarup was busy setting up the images, meting out framing advice to his volunteers. “It’s a little crazy now with only days to go for the November 16 opening but I am excited,” he said before taking us through his works. A chat...

For scenographer Swarup Dutta, questions on identity were a natural reaction to his socio-political being, with about 20 years in the arts, be it fashion, design, scenography or teaching. Therefore, the nomenclature of his first solo exhibition expressing this interrogation of identities titled ‘Kaw’ is no surprise — he is a Bengali artist living and working in Calcutta and seeking answers to questions like ki? (what), ke? (who), keno? (why), kokhon? (when), kothay? (where) and ki bhabey? (how), which all begin with the Bengali letter ‘kaw’.

When we entered the quaint gallery space of Akar Prakar at Hindustan Park earlier this week, Swarup was busy setting up the images, meting out framing advice to his volunteers. “It’s a little crazy now with only days to go for the November 16 opening but I am excited,” he said before taking us through his works. A chat...

For scenographer Swarup Dutta, questions on identity were a natural reaction to his socio-political being, with about 20 years in the arts, be it fashion, design, scenography or teaching. Therefore, the nomenclature of his first solo exhibition expressing this interrogation of identities titled ‘Kaw’ is no surprise — he is a Bengali artist living and working in Calcutta and seeking answers to questions like ki? (what), ke? (who), keno? (why), kokhon? (when), kothay? (where) and ki bhabey? (how), which all begin with the Bengali letter ‘kaw’.

When we entered the quaint gallery space of Akar Prakar at Hindustan Park earlier this week, Swarup was busy setting up the images, meting out framing advice to his volunteers. “It’s a little crazy now with only days to go for the November 16 opening but I am excited,” he said before taking us through his works. A chat...

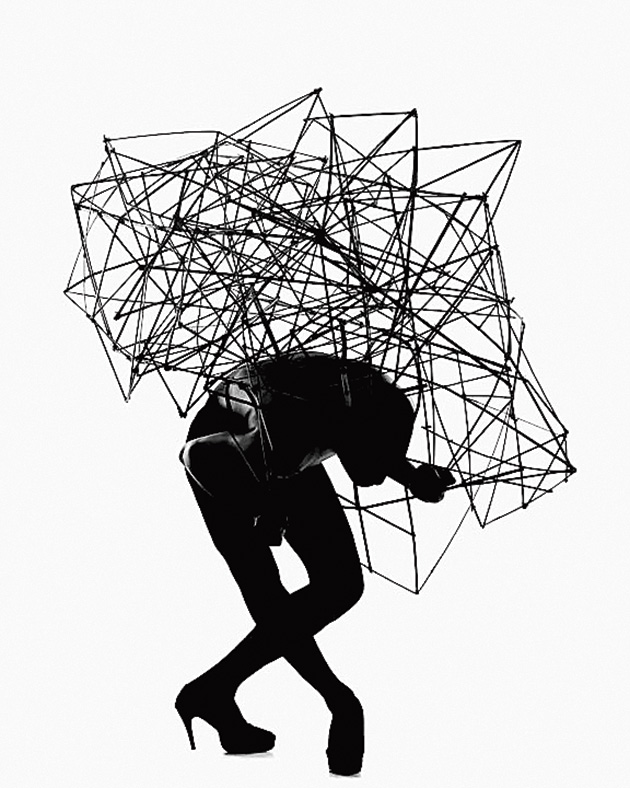

The Armour of Weaknesses has 40 images comprising silhouette-photography that resemble “charcoal sketches”. Swarup Dutta

Art on the streets: Swarup sent out a few of his models in the garb of the subjects of his exhibition on the roads on November 10, just to see how pedestrians would react. The response ranged from curiosity to wonder to amusement to a selfie opportunity. Swarup Dutta