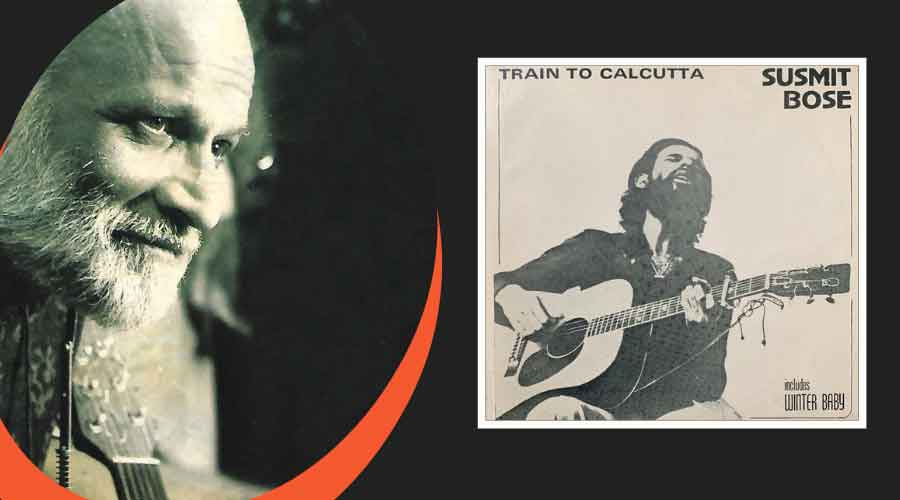

Out shopping for a record sometime in the 1980s, a boy spotted this white album with a picture of a man with long hair and beard, his head turned back ever so slightly as he is seated with guitar in hand. Susmit Bose, it said in large bold font. What? Bangalee singing ingraji gaan? Worth a listen, for sure. But then, he had gone to Harry’s Music on Chowringhee for Beatles, a rare commodity at record stores in Calcutta those days. There was Rock ‘n’ Roll Music, a double album, and he couldn’t resist buying it. He promised himself he’d be back next month, his monthly dole from a generous parent willing, and check out Susmit Bose.

He did. But Susmit Bose was not around. The last copy of the record - he couldn’t remember the title - was gone.

True story.

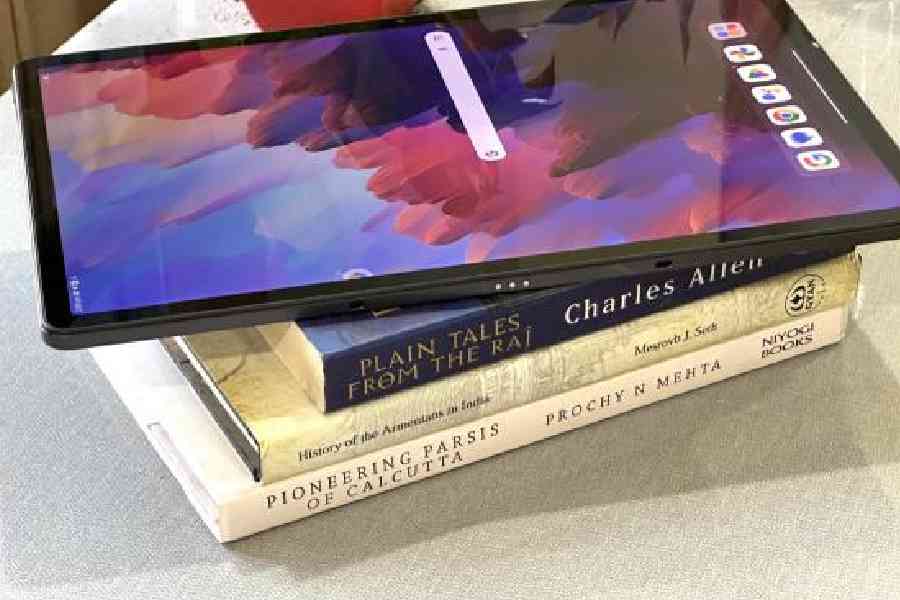

Now, four decades later, thanks to the efforts of an enterprising filmmaker and songwriter who tracked down one of Calcutta’s most diligent record collectors, a digital version of Train to Calcutta, one of the first LPs of English songs by a desi (1978), has been made available on streaming platforms. Then and Now - a double album that also features a collection of Bose’s later songs - was released on November 1, to commemorate the singer’s 70th birthday.

True story.

Bose, a Dilliwallah who went to school at Springdales, has, perhaps aptly, moved to Calcutta now. The beard is tightly cropped grey, the long hair almost non-existent. Yet the spirit of the troubadour remains. Joyously so. A Bob Dylan acolyte, who became one after becoming friends with Pete Seeger, Bose spends his time these days singing at open prisons of Rajasthan, foregrounding a reformist idea being spearheaded by a non-profit. He has a captive audience of thousands when he sings Hum Honge Kamiyab in jails. The prisoners sing along, and those witness to such moments, believe both Pete and Woodie Guthrie would smilingly approve.

Winter Baby was an early hit, its stark portrayal of a season coming alive in words that paint rather than tell: “Morning dew, the season’s dreams are gone away. What do they do they do not know.” The title track, about a boy on a train, is as real as it gets. Unencumbered by social messaging, it simply wants to tell a story. A guitar and a runaway boy. That’s the way it was that day, that’s the way it is today, and that’s the way it will be for ages for those who make their own road. As the years passed, Bose’s songs seem to come alive, embracing myriad strands, multiple hues. They acquire a firmer structure, the themes coalescing into definite ideas. Like in the smartly strummed and happily angst-ridden Walking Talking Contradiction. Or the purposeful Wipe Out the Jargon where he chides - ever so gently - the “restlessly confused and selfishly amused” today generation. Bose is now ready, allowing his creative branches to spread out. Hence, a piano opens and makes away for jagged guitar chords in Dear Sir. “Would you treat your mother, your sister, or your daughter, the way you treat women around?” he asks. A saxophone floats in unexpected. The solo clutches your heart.

Usha Uthup, the queen of Fever in a Kanjeevaram, calls Bose a friend for life: “he is iconic, a true pioneer of the kind of music he sings. His music is so inclusive, something we need in today’s world.” Nondon Bagchi, the now elusive and reticent elder statesman of progressive rock and culinary ruminations, believes Bose is that rarity we must hold on to: “Susmit has been around for five decades and still has a strong contact with his music. He deserves a lot of respect for surviving without giving up and without making his way by other means.”

Indeed, Bose comes across as earnest, down-to-earth and lively, someone who doesn’t take himself so seriously. At times, he’s self-effacing to a fault. In a lively conversation over Zoom with The Telegraph Online, he talks of running away from home, a la Bob Dylan; his original dream of being ‘Pandit Susmit Bose’, the time spent as a hotel crooner, the turbulent 70s of Leila Khaled, Marianne Faithful and Pratidwandi, All-India Radio’s mega cross-cultural hit with We Shall Overcome, and of course Mahatma Gandhi and that Train to Calcutta that got him to us. Excerpts:

Train to Calcutta is out after about four decades. What made you decide on the reissue?

When I came to Calcutta, I found there was a lot of interest in Train to Calcutta, my first album. Then, Jaimin Rajani (singer/songwriter and filmmaker) and a few others got together and talked about it. Jaimin suggested we bring out a double album and perhaps relaunch it. Because I am not in the mainstream, and because some of my music is commissioned by the development sector (Oxfam, Ford Foundation, Action Aid) these are distributed among activist groups and the development sector. And it doesn’t get out into the market. There are a lot of songs that people haven’t really heard. So, we decided on making a compilation, a second record of my later songs, the first record being Train to Calcutta. It was wonderful how Kalyan Roy had as-new-as a mint recording of Train to Calcutta which we took from him. We combined this and the rest is what is happening now.

I loved the songs, the feel and texture. They are heartfelt. What goes on in your head when you hear your old songs?

My songs are not fiction. Each song comes from stories, from people or a newspaper article or something on television that I see. I am also like a journalist, a music journalist. I just interpret what is happening and put it into words. Like, there was this incident when I was travelling somewhere and this young man came running to me and said, ‘how come Mr Bose, you write about social change and there isn’t a single song about farmers?” I said, ‘Well, I don’t have a story’. So, he was quite amazed. That was the time when there were a lot of farmers committing suicide. So, I ended up writing, The Son of the Soil. That is how the music comes.

The song Train to Calcutta is about this boy. His story remains unfinished. I am curious to know what happened to him.

He was without a ticket and was yanked off the train. Yes, it is an unfinished story. I don’t know what happened to this boy. I think it was Mughalsarai station. A cop was called, and he came with his lattha and all… And this little boy had no fear in him. He was like glass. He was pushed hard from the train on to the platform; but thankfully, they did not hit him, which was something that I was dreading, and I was ready to pick on it. He fell on the platform. And he sat there, and the train moved on. I can’t explain this to you, in those days children uncannily became my focus. Winter Baby (1971) is about child abuse, A Train to Calcutta is about a runaway child, that entire album has lots of songs about children.

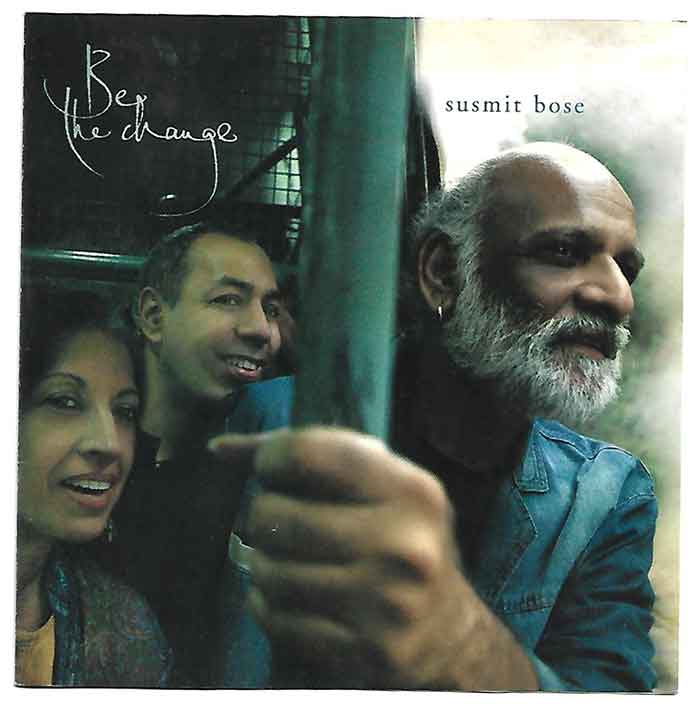

Be The Change

But why don’t you have a copy of your album?

I don’t have any of my work. I only have stuff from 2005 onwards. What used to happen was that people would come and ask and I would sign it and give it. Finally, I wasn’t left with any.

How has the Susmit Bose of the 1970s changed in 2020?

I don’t think I have changed. All the songs in Train to Calcutta were written when I was 16 or 17. And I was telling somebody that now when I listen to this, I find it quite trite… it’s like amateurish (laughs). But yes, the songs have a lot of emotion. As you rightly said, plain and simple. Not simplistic, but simple songs which didn’t make an effort to get across. So, now perhaps when I write, I write with a sense of conviction; that OK, I need to get this across. The only change perhaps is that I am slightly more mature in terms of writing lyrics. And I kind of picked up my skill from people like Dylan, Pete Seeger, Woodie Guthrie. Keeping the songs simple, not making an effort to hit hard, but the words just come out and hit you somehow; you know, it’s like a conversation.

You describe yourself as a journalist. One of the things we are told in journalism is that we need to be a bit cynical and not believe anything and everything we hear, especially from the authorities. So, are you cynical?

No, not at all. In fact, if you listen to my songs, you will find that I always end in a note of hope. There will always be hope in life. Because there are many, many more good people than there are bad. A lot of good things happen which we miss out on in our everyday life. And because the bad things are so gory, and they come so strongly on us, that we kind of tend to magnify. As a rule, I don’t watch violence. I don’t have a television set. I don’t listen to negatives.

I have one of your albums, Be the Change. I was struck by the relevance of the songs even today.

When I was a little boy in school, I remember that every school diary had the last few pages blank. So, each year I would on one page write the lyrics of Vaishnava Jana To. And on another page write the words of Where the Mind is Without Fear. These words were deep within me, I soaked them in. And I wanted to sing these songs at some point of time. So, in 2000 I thought to myself about the relevance of Gandhi today. I wanted to talk to young people who would listen to angrezi gaana. And tell them about ‘be the change’, tell them about Vaishnava Jana To.

What was your childhood like?

When I was young, and because my father was into Indian classical music, I grew up fantasizing myself as ‘Pandit Susmit Bose’, wanting to sing khayal and thumri on stage. But (in) those days, music was not really a proper thing to do for somebody coming from a so-called educated background. So, my father always kept me away from learning music, although great artistes, the likes of Ravi Shankar and many others, would tell him to teach me since I had ‘such a lot of interest’. When they used to jam, I used to sit outside the door and listen. And when the door opened, I used to run away.

I was a radical, and every now and then, my father would throw me out of the house. And I would sleep in a railway station or a park, only to be woken up at night by a policeman and pushed around. And after three or four weeks, I would go back home.

How did you get into western music?

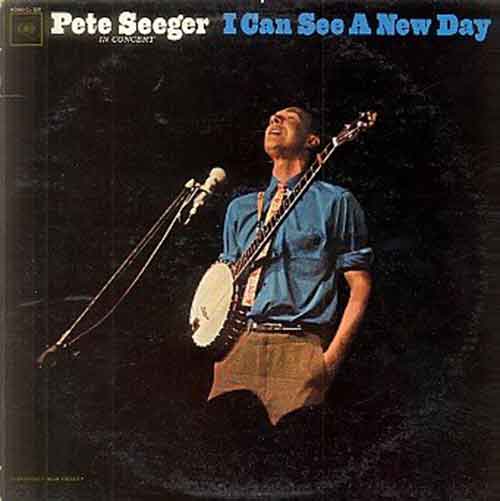

I belong to a school called Springdales in Delhi. Every year, we had our annual day and we used to put on a ballet with a social message. These were wonderfully done. In one of the ballets, we were doing Man Through the Ages, or something like that. And all of a sudden I heard a song on the PA. ‘I can see a new day, a new day, soon to be, when the storm clouds are all passed and the sun shines on a world that is free.’ My hair stood on end, and I ran to the booth and asked who was singing. The music teacher, who was very fond of me, handed me an album. The cover had a picture of a man with his head thrown back, singing. Just one man with the banjo. The song was, I Can See A New Day. And that man was Pete Seeger. So, I followed Pete Seeger because I had no clue about western music other than some pop songs of Cliff Richard and something like that _ you see I was so steeped in this dream of mine to be an Indian classical musician. But on that day, I gave up that thought of being an Indian classical musician. The audacity of me, I was 14 or 15 then, was that I told myself that I am going to write that kind of song, and that’s what I am going to do.

Then Dylan happened?

It was through Pete Seeger that I discovered Bob Dylan. In the 60s, when Dylan came on, everybody was making a statement _ through arts, painting or poetry, a song or whatever. I heard Dylan singing A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall. And I said, ‘wow, move over Pete Seeger, give way to Bob Dylan’. So, Bob Dylan came in and just to make a statement I wrote a song called, I am a Walking, Talking Contradiction. It was about all of us in college, and we were a bunch of contradictions. We wanted to do so many things. It was dichotomous times, there was a man on the moon, the Vietnam War was happening, there was the Naxalite movement, Leila Khaled (of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) hijacked an airplane (twice, 1969, 1970), Marianne Faithful exposed herself to promote women’s lib, people coming to India to attain nirvana as if to buy a piece of chocolate, there was transcendental meditation… And there was that dialogue of Dhritiman (Chatterjee) in Ray’s Pratidwandi where he was asked which was the most significant event of the times, the Vietnam war or man on the moon.

You started off singing in Delhi?

When I took to singing professionally, I was actually a pop singer because in India I just didn’t get a stage to sing the songs that I actually sing. Because the record Winter Baby (an EP) did so well that in 1971, I was thrown onto the night club circuit where I couldn’t sing these songs. I was just crooning, singing somebody else’s songs and making money which was just not my idea. But it worked. I was young and there was a lot of adulation, lots of media covering me and people running after me. There was a lot of money coming in. So somehow, I got swayed… I used to sing in hotels… in Delhi, Calcutta and Bombay. Then after 10 years, I went to England and came back and I sang at a hotel, wanting to sing folk. I went on like a troubadour with just one guitar and every night I got booed. That year, another hotel invited me to perform and I did that rock ’n’ roll stuff; you know, I was in a satin shirt and velvet trousers with my hair blown up, throwing the microphone, making digs at people, walking up to a woman and saying ‘you look lovely tonight.’ But people lapped it up. And I said that’s the end of the story of me singing in night clubs. This is not for me. So, I took a hiatus and gave up that kind of singing.

Your father was in the All India Radio.

The then director-general of AIR P.C. Chatterjee, aka, Tiny Chatterjee, who knew me because of my father, called me and said, ‘Your father has been with AIR for 30 years. How come his son ignores it’ So, I told him that I didn’t ignore it, but that I wasn’t given a chance. He then asked me if I could be a ‘regular artiste’ for Delhi B, which was a western kind of a channel, and whether I would agree to an audition. I said, ‘Who will audition me?’ There was this Mrs Kaur, who was then the producer of Delhi B, but she said no, ‘I can’t audition Susmit Bose!’ After that Chatterjee issued a written note and made me an A-grade artiste. So, I was at the level of people like Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan. I was getting money as an A-grade artiste and I was recording.

Pete Seeger: A New Day Now

How did you get involved in the production of We Shall Overcome?

Chatterjee asked me to bring out We Shall Overcome. So, I sang with poet Girija Shankar Mathur. (And) we translated about two-three verses in Hindi. And Anil Biswas, who was the chief producer of music, and whom I knew and called Kaka, asked me how I wanted to do this. I told him that I did not want to have a Bombay kind of sound and too much music on the song. So, he asked me to play guitar and sing the English song and arranged vocalists who would sing the Hindi version. It worked. It was fantastic. Then, Chatterjee asked every radio station all over India to do it in their language. Then there was a South Indian version, Marathi version and a Bengali version which Ruma Guha Thakurta did. We also had this huge concert at Vigyan Bhavan of We Shall Overcome in all the different languages of India. I was leading the Delhi radio choir, Rumadi was of course there, as were a number of brilliant people from across the country. And it got very famous. And I don’t know why people attribute that success story of We Shall Overcome to me. I didn’t do anything. But I took the glory. It was just the song, which has such a lot of power.

Just the very idea of having the song performed in all our languages is so wonderful.

During the Emergency, there were a lot of these underground groups where I was invited to sing We Shall Overcome. They were called basement singing. And during any kind of social activity, it was always Hum Honge Kamiyab.

You spent a lot of time with Pete Seeger. Was it during his Hudson River project?

Yes, I did. But more through letter writing. And he was a prolific letter writer. I couldn’t keep up with the old man. If I wrote one letter, I would get three from him in response. And every time, he would send me something in it, a leaf, a flower. We got along very well. We met up finally to do a sort of impromptu concert at the Hudson River. That was a little dump yard which he wanted to clear and make it into a park for people from all walks of life and their children to come and play. But the government did not allow him to pursue it because after McCarthy, everybody was a little scared of Pete Seeger. Anyway, he got a group of young people and they all worked on that place, and they built a park. I was in Canada then, and his wife, Toshi, called me and told me that Pete wanted me to come to Beacon for the inauguration of the park. He told everybody that he had a friend from India, and that we would do a song together. I suggested This land is Your Land. So, the old man was singing, ‘From California to New York island…’ and I was saying, ‘From the Gulf of Cambay to the Brahmaputra…’ And he stopped the song, and said, ‘Those are new lyrics.’ And I said, ‘yes, those are new lyrics that should have been there. Woodie did not write it just for here!’. And Pete looked at me for a long time, and asked, ‘you have more lyrics coming in?’ And I said, ‘you continue...’ And so, he got on his banjo again, tang-ta-tang-ta-tang… It was quite an exotic thing with my Hindi singing. It was wonderful. It was so much fun. And the crowd was ecstatic, cheering along. And Pete never forgot that day. Pete loved Calcutta. He also mentioned Kabir Suman and how he knew him well too. He was dying to get back to Calcutta.

Thank you, Susmit Bose, for talking to us. And congratulations on the album.

Post script: Susmit Bose says he stopped listening to Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger intently from the time he started writing his own songs, so immersed as he was in living his audacious dream. Jaimin Rajani, the producer of Then and Now, talks of how their mutual love for the “Dylan gharana” of music helped them connect despite the difference in age. “When I first heard some tracks from Train to Calcutta, I instantly fell for the simplicity of the lyrics, melodies and the inventiveness. I wanted to listen to the entire album and release it digitally to prevent it from getting lost forever,” says Jaimin, who has scripted If Not For You, a documentary on Calcutta’s love affair with Bob Dylan.

So, it’s here. Train to Calcutta is chugging again; dusted, oiled up for another fresh run. Hop on. Enjoy the ride.

Susmit Bose with Jaimin Rajani, Nondon Bagchi and Usha Uthup