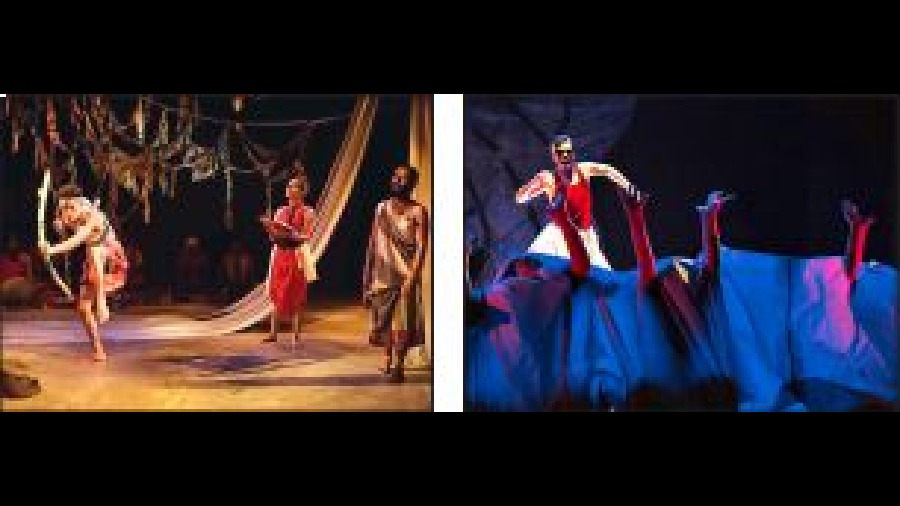

Bhumisuta Das of Gobardanga Naksha, previously identified in these columns as a young theatre director to look out for, has come up with an engaging interpretation of Chitrangada (picture, left). Deliberately postmodern, Das’s retelling is irreverent and playful, more invested in raising questions than supplying answers. It relentlessly critiques the Chitrangada myth even while performing it. Arjun is stripped of his machismo and, in keeping with the mock-epic nature of the performance, relegated to the shadows. Das teases out distinct aspects of Chitrangada’s character and has four actors playing the split selves in a sardonic commentary on the absurd societal expectation that women should embody several qualities. Plurality underpins the conceptual framework of the performance that ropes in multiple languages and ethnicities.

Chitrangada accommodates various performance registers, ranging from folk-musical storytelling genres to extremely demanding indigenous physical theatre that involves aerial, rope acrobatics. The absence of any directorial intervention to blend the divergent styles of performance into a uniform ‘design’ is praiseworthy as it gives Chitrangada a patchwork texture. The thread of profanity-infused slapstick holds everything together — this deployment of the comic, bordering on the ridiculous, is as good as postmodernist theatre gets. Among the performers, all rock-solid in their roles, Parikshit Gogoi stands out with his subtle tonal variations and fluid movements as does Gobardanga Naksha’s homegrown talent, Titly Chakraborty, who is maturing into a fine performer.

Retellings are a trend these days, as is evidenced by Ashokenagar Nattyamukh’s production, Mr. Right (picture, right), directed by Avi Chakraborty. A Mohit Chattopadhyay classic, Mr. Right is an absurdist fantasy about Rajat (Sumit Kumar Roy) whose right hand begins to act independent of his intent after an accident. Although billed as a ‘deconstruction’ of Chattopadhyay’s drama, the performance does not seek to extract, at the level of meaning, irreconcilable dissonance and discordance, which is generally the aim of a deconstructive reading. Rather, Mr. Right closely adheres to the written text, with Chakraborty attempting to create — he mostly succeeds — a performance design seldom attempted for this text. He has been ably supported by his stage, music and light designers, Debasis Dutta, Tamal Mukhopadhyay and Subhankar Dey, respectively. The deliberate exaggerations, brought about through many-hued lights, surreal ambient sound and heightened non-realistic acting, are elements that accentuate the vital aspect of fantasy in Mr. Right.

This parable about a part revolting against the whole can be interpreted as an individual suffering from a special kind of dissociative identity disorder or as a society that remains severely splintered — Mr. Right chooses to emphasise the first option. Thus, Rajat becomes the unwavering focus of the play and Sumit Roy delivers a power-packed performance. While the sequence with a pair of scissors showcases Roy’s abundant skill in acting with his body, the scene in which Rajat launches into a long, angst-ridden speech addressed to his wayward hand is proof of Roy’s ability to create poetic magic with words.