A title is an anchor, but also a limiting tether. So Cima chooses to call its current show, on till January 30, Untitled. It traces how, from vintage modernism to the fizz of contemporary colloquialism, concerns recur through stylistic shifts that five generations of Indian artists have negotiated.

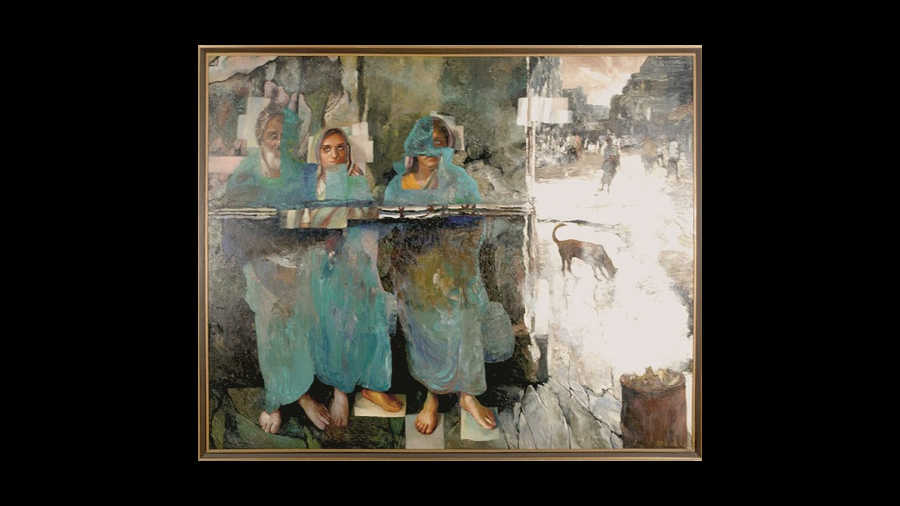

If Jamini Roy’s post-Impressionism approaches the landscape with Wordsworthian romanticism, Paramjit Singh’s dense brushwork makes it an immersive experience. Gaunt, famished, existing on the margins, Somnath Hore’s figures in his etchings appear as non-beings in their abdication of agency, dissolving, in Massacre, into smears the colour of dried blood; the marginalized remain fearful and mute in Jalil’s Family (picture) by Bikash Bhattacharjee. However, their descendants return in Prashant Patil’s series with a combative resilience. And through the lens of Soham Gupta their insouciant defiance resists victimhood as they wrest an orbit for themselves in the underbelly of the city.

Because, as Manish Moitra’s disparate monochrome images suggest, their robust stoicism pulls them through crises that would fell the pettifogging middle classes. That’s why, even where Nature might suddenly turn into the furious Eumenides — as in the Sunderbans — people mull strategies, in Arko Datto’s video, to counter the perennial threat that haunts them: Where Do We Go When The Final Wave Hits? That makes its purple skies, tense trees and black waters ominous rather than epiphanic. The precarious life of subalterns thus lends to Harendra Kushwaha’s worn, torn, Nepali paper rug a metaphoric reach. It’s not just the reference to destitution and homeless drift; implicit in his A Piece of Nothing is the ubiquitous violence — gender, caste, class, political — that stalks the helpless. Like the unnamed, unseen menace in Shakila’s collage. Or in Chittrovanu Majumdar’s brusque slashes of dripping paint that capture a headless figure with a raised arm.

This ubiquitous violence remains imperceptible for it doesn’t take on an epic scale like the Mahabharata carnage that Ganesh Pyne depicts. But Gopal Ghose sanitizes Calcutta Killings into a deceptively colourful image, gore eliminated. And Jogen Chowdhury’s forensic detachment scrubs strident horror off violence, turning the raw gashes on a dead man into pretty patterns, as Husain and Rameshwar Broota — the latter very precise in deleting the man from his arms — hint at the cold anonymity marking State violence.

Expectedly, urban angst simmers in several artists. Palaniappan’s whiplash lines seem rootless in their aimless rush; the disorientation of the individual in his imploding universe comes across as a painful, muffled understatement in Sumitro Basak’s Shattered; and the city is overbearing, claustrophobic, colourless in Sanjeev Sonpimpare’s canvas. But it’s Jaya Ganguly who turns the Baconesque disintegration of selfhood and identity into a cathartic, almost metaphysical allegory.

In spite of the persistence of despair, the quirky poetry of impromptu play shines through in Shreyasi Chatterjee’s series, Kitchen Diary, in which vegetables and fruits, their flesh and colour, structure and peel, are assembled with an elfin whimsy into quaint, comical forms. A similar sense of gauche delight is echoed not just in tribal art — represented here by the Gond artists, Ram Singh Urveti and Narmada Tekam — but also in Ram Kumar’s child-like Durga, while the irreverence of Anupam Basu’s video turns Hanu-man

into a Puja marquee display with winking lights.

Sailoz Mookherjea’s sensitive brush and Hansa Kumar’s fine weave of lines, dashes and stipples invite a lingering gaze. But it’s Jitish Kallat’s suite of 68 prints that keeps the visitor rooted with its captivating montage of subtle, hesitant inflections of tone and texture, blurry images and undulating, dissolving contours, with little scars and rips unsettling serene vistas. Did Onomatopoeia/The Scar Park [sic] arise from a complex of inchoate, indefinable feelings in search of an elegant reticence?