This is a refreshing antidote to tortuous conceits and involved correlatives that often clog contemporary art expressions. Paula Sengupta’s online show, The Porcelain Rose, presented by Gallery Espace, seeks to retrieve the childlike wonder that turns the mundane into the magical. The traditions of Aesop and the Panchatantra, or even those of modern fables from the likes of Saint-Exupéry and Richard Bach, don’t stale, enriching the supple imagination of both children and unjaded, non-adult adults, sparking fantasies in which anything is possible. Even the peaceful co-existence of predator and prey. In fact, the title itself reminds you of The Little Prince. Perhaps all things of doomed beauty can be given the very same name, The Porcelain Rose.

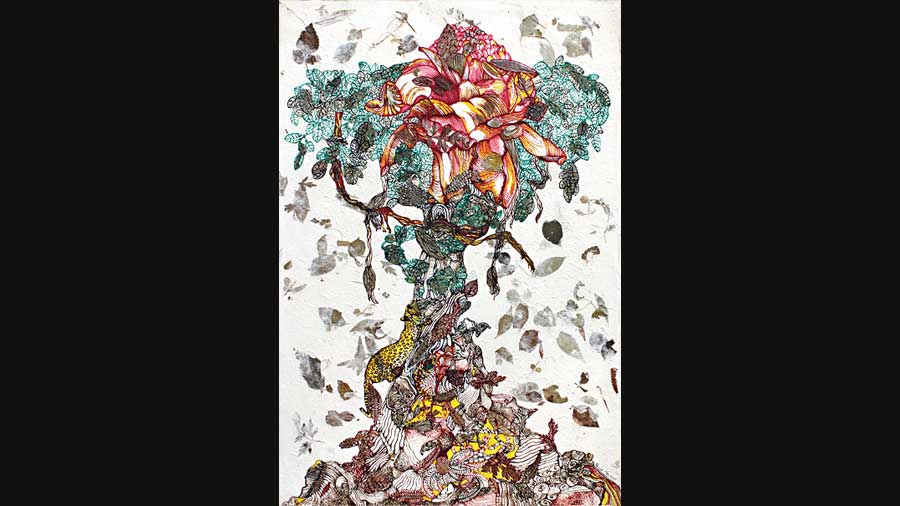

It’s in this fertile innocence of illogic that Sengupta’s allegory of talking animals and idyllic co-existence blooms. Brisk, sprightly, free-flowing lines conjure up colourful images of giraffes and trees, peacocks and tigers, zebras and lions in ink on flora-embedded rice paper, bringing the material into the message, in a simple animation of stilted movements, brought to life with delightful forest sounds and, fleetingly, a voiceover. Photos from Sikkim, Kanha and the Serengeti Plains are included, perhaps for their metaphorical resonance of beauty doomed.

A visit to Tanzania’s Ngorongoro crater in early 2020 made the artist feel blessed by its Edenic microcosm of harmony because it seemed that “all animals live in perfect consonance”. Yet her first animation short, Sunehra’s Folly, squints impishly at haywire material aspirations that unhinge Nature’s pristine design. When Sunehra, the giraffe, borrows alien plumage — of the peahen — not only does he invite ridicule as Sukumar Ray’s Kimbhut did, compromising his own identity, he also sets off a shrill alarm in the entire forest of Sundar Jaal. Just as the human animal’s reckless destruction of Nature’s design releases multiple, irreversible, boomerang chain reactions. Sengupta’s anguish at how the Dockwood Tree of Buddhist lore degenerates into the Tree of Desire tells you that the myth of suicidal lemmings is the reality of Hobbesian individualism.