With the second wave of Covid-19 wreaking havoc all over India, it may now sound absurd that Calcutta theatres seemed to have come to terms with the deadly virus until a few weeks back. February and March saw scores of state-sponsored theatre festivals.

Minerva Natyasanskriti Charcha Kendra’s week-long festival at the Minerva Theatre may have missed out on outstation teams, but made a welcome effort to prioritize recent Bengali adaptations of celebrated Hindi plays. Most of the productions — except for Mukhomukhi’s adaptation of Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug (February 24) — have been reviewed on this page. Working on Pranata Bandyopadhyay’s Bengali translation of Bharati’s psychological exploration of the after-effects of the battle of Kurukshetra, the director, Poulomi Bose, decided to play it straight and conventional. By relying heavily on verbal exchanges, Bose left the subtle subtexts unattended, thereby turning it into an old-fashioned display of oratory. Debshankar Halder’s occasional flourishes as Ashwatthama, the pivot, and a convincing act by Debnath Chattopadhyay as Jujutsu did manage to save the day. The magical moment came towards the end when Soumitra Chattopadhyay’s recorded voice — for Krishna — resonated in the dark crevices of the old theatre.

The newly formed Paschimbanga Hindi Akademi hosted Rashtriya Hindi Natya Utsav in three phases. This reviewer could not make it to the Siliguri and Asansol chapters. However, the Calcutta chapter (March 7-9) held at Sisir Mancha sprang a few major surprises.

Delhi-based Shri Ram Centre for Performing Arts Repertory visited Calcutta after a few decades and premiered Anveshak, their latest production, on the inaugural evening. Written by the veteran, Pratap Sehgal, Anveshak focuses on Aryabhatt, the fifth-century Indian mathematician-cum-astronomer. Sehgal used little available resources to script a remarkable drama that pits Aryabhatt’s prodigal talents and scientific research against the custodians of scriptures with the State maintaining a fine balance. Although Bertolt Brecht and Utpal Dutt have worked on similar themes in the past, Sehgal’s ability to explore court intrigue during the heyday of the Gupta rule and the academic environment at

Nalanda stood out. The director, Ayaz Khan, worked with a young team and collaborated well with the light designer, Souti Chakraborty, to craft a memorable opening sequence with dimly lit balls held by the actors, denoting the heliocentric universe. The 100-minute-long production suffered from the lack of experienced actors, but Saransh Dikshit, playing the protagonist, displayed maturity beyond his age. A strong supporting cast led by Aimen Khatoon, Shubhang and Hemant Kumar Rai made up for the rest.

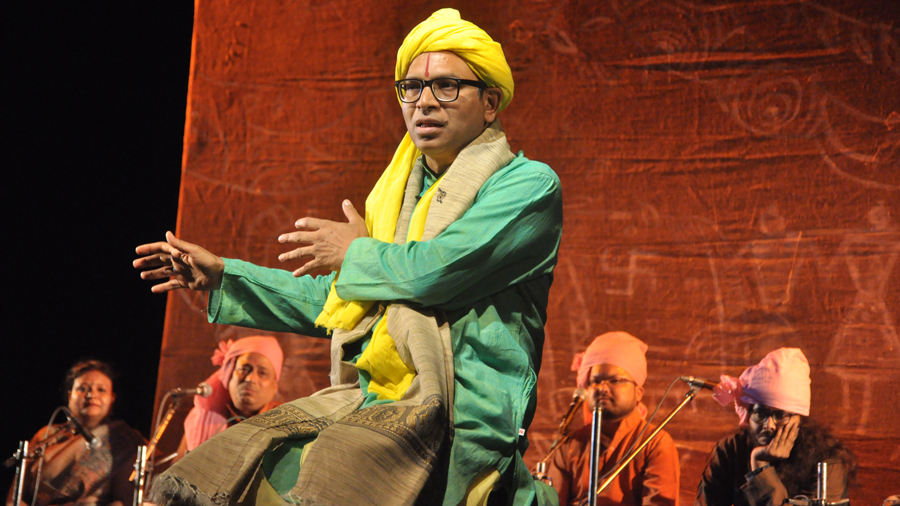

The pièce de résistance of the festival was Nugra Ka Tamasha (picture) by Kala Mandali, Delhi. Essentially a solo act, scripted, directed and enacted by Suman Kumar, this 105-minute-drama celebrated the performativity of community theatre practice. Kumar kept it simple — deceptively simple, à la parable. Working on an age-old folklore that narrates and relates to the immediate audience in the same breath, he punctuated his narration with musical interludes — a collation of songs rooted in agrarian India and played on traditional string and percussion instruments. They underscored Kumar’s easeful yet sensitive acting as he kept weaving tales within tales, bringing forth his environmental concerns towards the end. It was a masterclass in acting — understated yet supremely communicative.

The festival ended with Jabalpur-based Vivechana Rangmandal’s competent Hindi adaptation of Badal Sircar’s Ballavpur Ki Rupkatha. The director, Pragati Vivek Pandey, left the script as it is, while the seasoned actors — Vivek Pandey, Ishani Mishra and Ashutosh Dwivedi — played to their potential, ensuring a laugh riot.