“About 25,000 unarmed people. Forty launches hemmed them in and then the police pounced on them. People were dying, butchered like livestock... On this island, 20 miles in length and eight miles in width, on one side the police were advancing mowing down people with their bullets, and the survivors and those fearing for their lives were trying to escape in the opposite direction leaving behind the dead… Police were not only killing but were also involved in large-scale rape. Rape is an extremely effective tool. So there were strict instructions from the current administration — it has to be done. People have to be terrorized. If possible, one by many... that was the only way Marichjhapi could be gradually liberated.”

These lines from Manoranjan Byapari’s short story, “The Undead”, confront us with the full horror of the Left Front government’s massacre in 1979 of low caste refugees — mostly Namasudras — from Bangladesh whose crime was seeking refuge at Marichjhapi in the Sunderbans instead of being relegated to the hostile terrain of Dandakaranya. The Left Front government had promised to resettle these hapless people but instead it unleashed Communist Party of India (Marxist) cadres and the police, who carried out carnage with mindless brutality.

Soumya Sankar Bose’s anodyne and occasionally lurid photographs displayed in the exhibition, Where the Birds Never Sing (2017-2020), presented by Experimenter, Ballygunge Place, carry no trace of this annihilation of all human values, although, if the press note is to be believed, he had set out to do so by “Employing re-enacted memories, in-depth research, interviews and oral histories of survivors...” Bose’s stylized, theatrical and rather pretty pictures — the fruits of a “long-term project” — betray little or no comprehension of the unparalleled scale and savagery of unbridled State violence witnessed in Marichjhapi. Questions can be raised about the location of the exhibition. Is a white cube with its associations of exclusivity the right place for holding an exhibition on one of the many bloodbaths that the then government got away with? It needed the work of several dedicated researchers to break the silence and salvage it from transforming into an administrative detail. Bose’s fanciful work does not add anything to the valuable information already gathered.

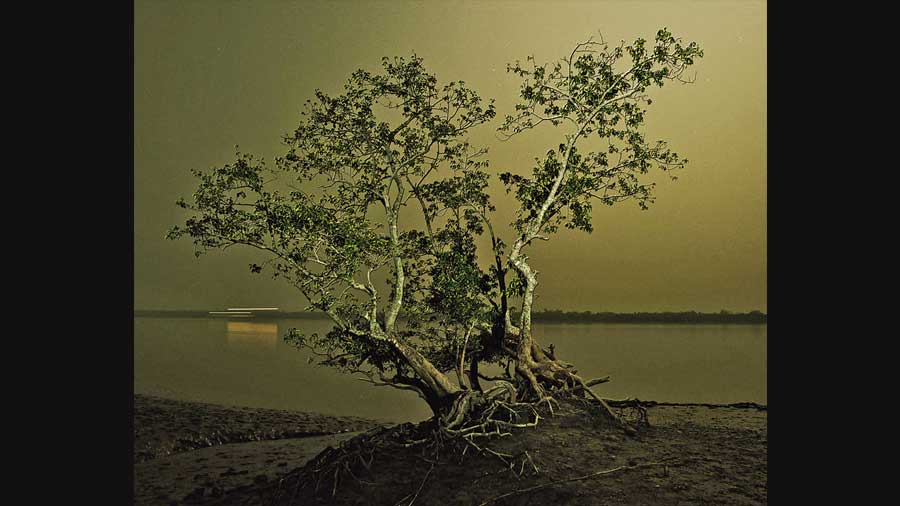

In Bose’s exhibition there is this series of images that capture the serenity and beauty of the isolated island of Marichjhapi with waves crashing on the shore. Caught in half light, they carry no hint of bloodshed, unless one takes into account a mysterious object floating in water. Bose has used a flash to illuminate trees and foliage but they throw no new light on this area of darkness. One tree is bathed in red light? Was Bose, in keeping with Macbeth, “Making the green one red”?

Bose has in the past successfully used the tableau vivant for his black-and-white photographs of fading jatra artistes. He has attempted that in his Marichjhapi project too with pretty appalling results. What is that woman doing on top of a tree like one of those spirits from Parashuram’s Bhusundir Mathe? Why was the man caught with his pants down? Was it a bout of diarrhea that humans become susceptible to in the Sunderbans and which killed many Marichjhapi survivors? Even the pistol and machete are sans menace. No trace of wanton violence.