When a simple image, neither loud nor logorrhoeic, can plug into disturbing references at once, it becomes the pick of the show, in this case Constellations, seen at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity till March 13. Chandra Bhattacharjee’ s painting of a deer, stunned by a low-wattage light at night in a forest, suggests unseen but ubiquitous perils and immanent violence in its stealthy depths. Its diffused sepia-greys evoke shifting shadows and muted lights as it perspicaciously links mythology, the environment and unforeseen contingencies through this symbol of the vulnerable prey. Its companion image, that of a bare-bodied hunter with a flaming torch, is no less a victim in a wider ecosystem.

That category — of a vulnerable victim — includes migrant labourers, whose long march across the country became a testament to the brutal apathy of authority towards the vulnerable in serial tragedies last year. Arindam Chatterjee’s sulphurous landscape through which they trudge in his Second Home-coming has no finite borders of time and space: the ambience spills over into a world that’s grimly dystopic. Watercolour, infused with charcoal, percolates the air with a sooty miasma. And, as in Bhattacharjee’s work, possible perpetrators appear as condemned as their trapped, skeletal prey.

What Jogen Chowdhury exhibited — eight of which could be called mixed media drawings — were done between 2019 and 2021 and reaffirm his vocabulary but extend it as well with interesting variations. Heavy, brusque lines stride about chaotically, looping into letters at times, to erect two vertical structures in Untitled IX, locked in a confrontational exchange. In VII and VIII the lines that bloat into slithering smudges are tangled to form denser, darker, heaving tapestries in I & II. Another senior, Shuvaprasanna, revives in this 2021 suite what was always his forte: exacting brushwork, seen here in his portraits of two watchful crow couples and horizontal cityscapes of ramshackle, charcoal-matted rectangles jostling to breathe.

Arunima Chowdhury registers a change of mood in her paintings of women who have a benign, inviting, wholesome femininity about them. Their identity is well-integrated; their sense of self at perfect ease with their social role. The narrative around them has a comforting serenity because these home-makers and mothers embody a certain domestic beatitude, no anxiety or conflict. One set with easy-flowing lines and full bodies, that quote Kalighat pat and Jamini Roy in passing, is characterized by an earthy, almost lethargic composure. The three women in the other, with reverie in their eyes, have been given a touch of feral grace.

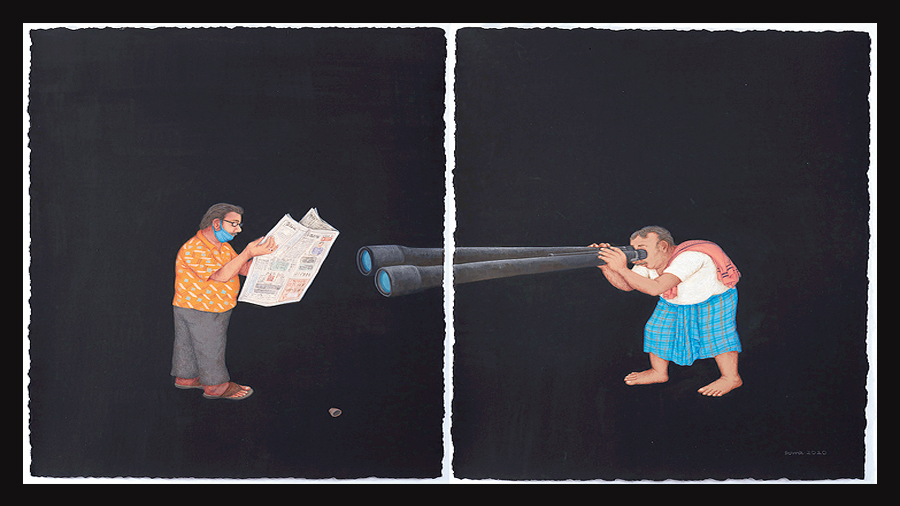

Soma Das, on the other hand, casts wry glances around, to lend a perky, caricatural Bengaliness to the people she portrays, their social profile clearly defined (picture). Her humour isn’t without heart, though, as The Last Woman in the Queue, Unaccustomed Occupation and Street Food Stall VIII and IX show, indicating the daily dare that the stoical, resilient aam aurat must risk, especially now. Elsewhere, the Covid-19 protocol of distancing and washing is turned into telling tableaux of farce.

Anjan Modak doesn’t let sentimental sighs sag his sympathy for the subaltern either, particularly the migrant labourer who distracts himself with kirtan as he burns his bones while, echoing a Sukanta Bhattacharjee metaphor, his tool becomes a wedge of melon: in the realm of hunger everything is utterly prosaic. The work that summarizes a migrant couple’s irony is The Ephemeral Shelter. They build homes for others, but drift homeless themselves, lying down wrapped in the unfinished wall of a building as though they were filling in a kathi roll. Tamal Bhattachrya, aloof from social concerns, explores expressive nuances of earthenware and stoneware, partly inspired by folkish dialect.