It’s an arresting installation, like a scene right out of a new-wave film of the 1970s, rife with unstated menace. From a faux mud wall facade, made with jute, plaster, sticks and newspaper, hangs the frame of a hurricane lantern that looks charred. On shelves are arranged the skeletal remains of a few more blackened objects: pots and pans, locks, kerosene lamp holders, baskets. Elsewhere, on another faux mud surface, more things are lined up: kettle, kerosene container, a mug, a clock, and so forth, intricately webbed with tentacles of frozen soot.

These everyday household objects immediately evoke village life with its fragile precariousness. It seems as though they were burnt by a ravenous fire and then retrieved from the cinders, perhaps in an attempt to redeem the daily routine torn by some violent disruption. Retrieving blackened shells suggests a kind of gesture: to preserve belongings not for their utility but to perpetuate their metaphoric significance as testament and memorial. Because, of course, the disruption, the violence aren’t over. They simmer in the stubborn riff of spooky shadows that cling like cobwebs to the surface behind and dance with the light to anchor Time and tragedy in collective memory.

No wonder their creator, the CIMA Awards winner of 2019, Prashant Shashikant Patil, whose solo show is on at the gallery till March 13, has been described by Ushmita Sahu in her catalogue essay as a choreographer of shadows. He creates with light a haunting, immersive theatre of ragged, sentient penumbrae that take up the refrain of the still, coal-black objects to hint at the uneasy ellipses and ampersands, the prelude and epilogue around them. They shrink or grow into looming monsters, stand still or quiver, shift and intersect according to the play of light. But, clearly, this stalking aftermath refuses erasure or burial, invested with the kind of timeless relevance that brings to mind Light Sentence, by the Palestinian artist, Mona Hatoum, disturbing for its socio-political implications.

Where Patil differs is in his creative strategy. Instead of wire, which is firm for scaffolding as well as malleable for shaping, he adopts a technique of elegant, inspired simplicity. He uses the hot glue gun to both sketch ridged lines on acrylic sheets or paper — in black, white, beige, yellow and magenta — and construct objects. In other words, he wields the tool to draw 3D relief images or patterns on flat surfaces and also assembles sculptures with it, summoning up shadows as the interpreter of his imagery to evoke a range of resonances. If some works have a dark undertow, there are also those that are chatty, wryly nostalgic, reflective.

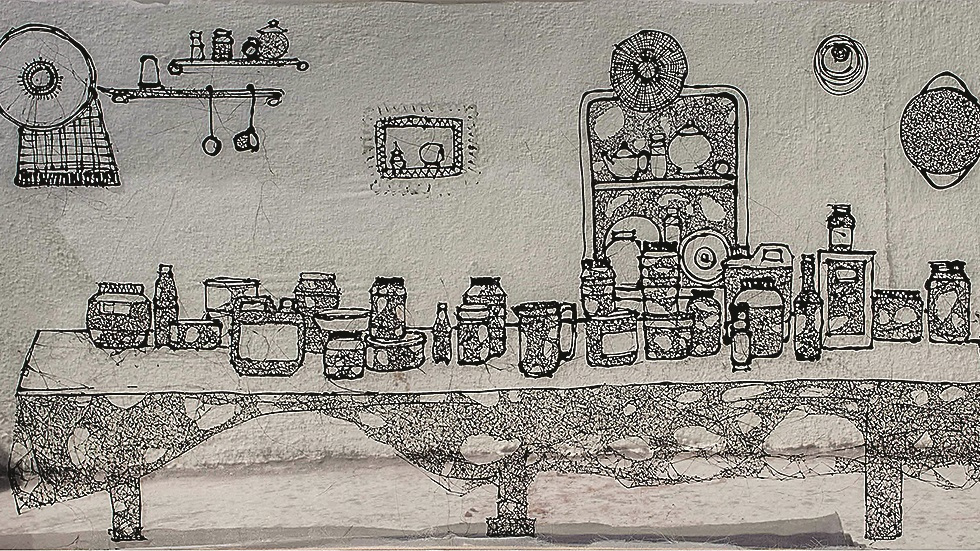

Like a careful cartographer this artist from Koregaon, Maharashtra, weaves a mesh of scribbles to map ambience and yearning as memory is revisited on transparent acrylic sheets or screen printing cloth. Tapestries of lines and tears, outlined forms and the counterpoint of negative space lend a beckoning seduction to his tableaux with charpoys and jharoos, earthen ovens and woks, bottles and tattered fabric. There’s a comforting familiarity in the image of a child lying on a charpoy; an infectious intimacy imbues another with a cupboard and a table full of jars and bottles; a third captures boots propped up on the window: home may be physically distant for the artist who passed out from Visva Bharati, but endures in his reveries.

The finale is reserved for one corner. A carpet of filigreed black lines laid on a glass table top with a grinding stone in the middle casts its commodious shadow on the floor that’s like a worn, antique rug. It echoes the indefinable durability that die-hard romantics long for in Indian village life.