Chittaprosad is the poster boy of protest. The deprived and the downtrodden find their voice in his extensive artwork, from his heartrending visual reportage of the devastating 1943 famine that took a heavy toll of human lives to his cartoons of despots and money-grubbers and his later visions of a life of paradisiac bliss in unspoilt backwaters. So, is it surprising that the relevance of the online exhibition, People’s Artist — Chittaprosad: In Solidarity, In Solitude (October 10-November 15), has increased manifold today? A time when the Opposition — fragmented and crushed though it is — is up in arms against the Bharatiya Janata Party government’s use of brute force to splinter the country along sectarian lines and to push through various legislations aimed at destabilizing the country’s democratic spirit and set-up. When the hard-won rights and interests of Indian farmers and workers are being sold out to crony capitalists. When Delhi is besieged by angry Punjabi farmers protesting against the new farm bills that promote corporate interests at agriculture’s expense. When dissent is equated with treason. And when the exodus of biblical proportions of millions of migrant labourers is still a living reality.

This is one in a series of exhibitions being jointly organized by Victoria Memorial Hall and the Delhi Art Gallery, which has already mounted the panoply of Bengal art titled Ghare Baire in the Currency Building, under the jurisdiction of the Archaeological Survey of India. It still remains a mystery why and how a commercial art gallery, namely, the Delhi Art Gallery, which, of late, goes by its acronym, DAG, and which has taken upon itself the task of creating various museums to showcase the gallery’s vast collection, was chosen to highlight Bengal art in the Currency Building. The latter was earlier designated to house the long-awaited Bengal chapter of the National Gallery of Modern Art.

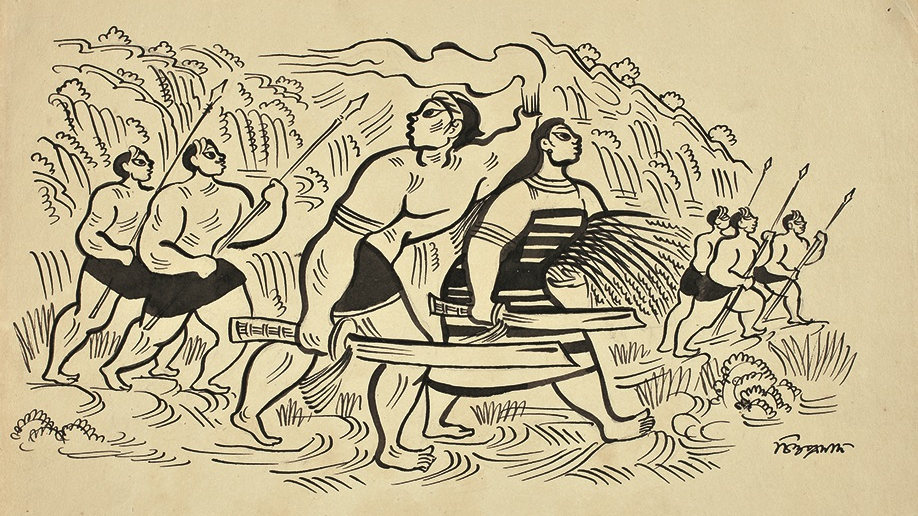

The Victoria Memorial Hall and the Delhi Art Gallery have also roped in the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences to organize various webinars on Chittaprosad’s art and the works he created as a member of the Communist party, initially creating posters and drawings. The artist, who never received any formal training, is still remembered for wielding his art like a weapon to buttress the struggle of workers, farmers and the oppressed. The party had assigned him to cover the famine. Little wonder that most copies of Chittaprosad’s eyewitness account — both visual and textual — published in Hungry Bengal were burnt by the British government, which banned the publication. The irony of an organization under a government that is no less tyrannical promoting the very political art of Chittaprosad cannot be lost on viewers. It is a case of the devil citing the Scripture for his purpose. But the biggest irony is that the works of artists such as Chittaprosad and Käthe Kollwitz, with whom the former has much in common, have become marketable commodities. A diehard socialist and pacifist who later leaned towards Communism, Kollwitz conjured up the horrors of wars, hunger and peasant uprisings through her agonizing images of women who had lost their husbands and sons, orphaned children and other visions of suffering and death seen through compassionate eyes. Yet both artists have fallen victim to the very capitalist forces they fought all their lives. But isn’t that the logic of the market?