Between the Harlem Renaissance (1918-1930s) and Rosa Parks’s historic defiance in a Montgomery bus in 1955, there rose the voice of colonized Africans in Paris —Aimé Césaire, Léopold Senghor, (the first president of Senegal) and Léon-Gontran Damas — who invented a term for a new Black consciousness: Negritude. Its unapologetic affirmation of identity shakes off white people and white-centrism from Black reckoning to assert a politico-cultural paradigm as relevant now as in the days of European colonialism.

That’s why a travelling exhibition of African-American artists from Historical Black Colleges and Universities, curated by the artist and educator, Peggy Blood, was titled Negritude, and hosted by Emami Art. It reminded viewers how white-centric modern art history was for the greater part of the last century. Although things have been changing, the mix of pain, protest and pride written into Black cultural expressions endures.

About 30 works or so by some 26 important African-American artists, both dead and living, were on view, with tributes figuring prominently as a theme. Like Ricky Calloway’s pop-art tribute to the Pioneers of the Harlem Renaissance. But its celebratory tone pales next to the brutal irony in the dark visual anthem of his oeuvre which you see on the internet. Another expected tribute goes to Martin Luther King from Clarence Talley.

Cleve Webber remembers a Black dancer, Gregory Hines, with quick acrylic smudges lending to the lanky, stretched-out figure’s speed and buoyancy. This particular work and Terrance Robinson’s mixed media guitar from his Jazz Homage series proclaim the Black genius for music and rhythmic movement that’s acknowledged world-wide. But Philip Dotson’s Influence of the Life of Emmitt Louis Till — an unremarkable oil, in fact — has a chilling effect when you uncover a forgotten fact from a murky skein of incidents, accusations and prejudices of long ago: the lynching of 14-year-old Till in 1955 in Mississippi.

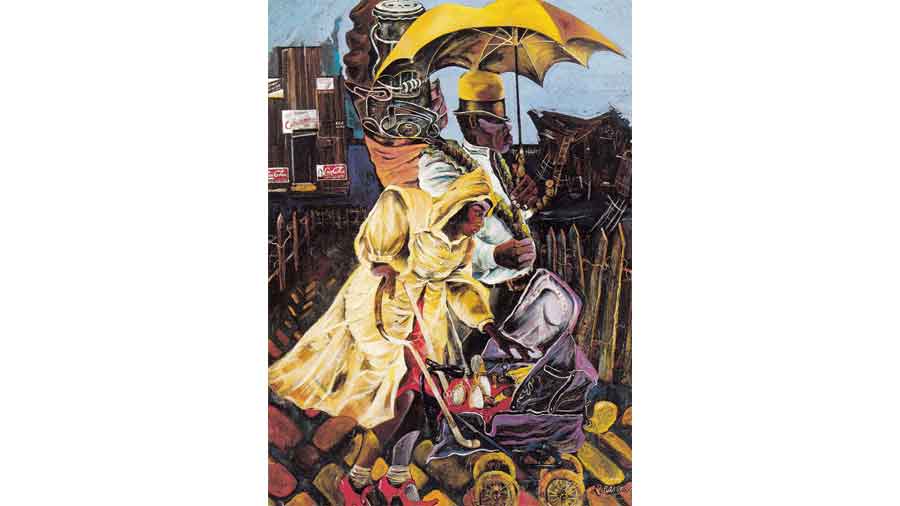

But hope does dawn in Freedom Morning by Claude Clark (1915-2001); only, it seems naïve against the embattled resilience of a couple by Lee Ransaw who seem to be Heading North (picture). Migrating with their belongings, in other words. Does the digital print refer to the socio-economic divide between the North, with free labour in industry, and the South, dependent on slave labour in plantations? Meanwhile, sympathetic evangelists, unmindful of harm to their bodies, were hyperactive in saving Black souls from perdition. Johnnie Maberry’s two mixed media canvases with blurred, textured paint script an unconscious sub-text:the religious side of slavery which buried their African identity under Christian names and white-ordained lifestyles.

Two abstract landscapes are included, but neither is happy. Garden by Louis Delsarte (1944 – 2020) is a seething jostle of acrylic colours fractured by quaking white lines. Peggy Blood’s oil, Passing Through, captures an unstable land exploding into viscous splashes of chrome and greys. Her digital print, Asimah, is disturbing in its suggestions of cringing withdrawal. The stoical resignation in a young face in the digital print of a monochrome litho by the American- Mexican artist, Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), is no less disturbing. In the mocking style of Benny Andrews (1930-2006) in Diva there’s an understated vulnerability, also reflected in Dennis Winston’s monochrome woodcut print, Going Home, in which a daily routine becomes a gesture of forbearance. Noticeable works also come from Tracie Lee Hawkins, Varnette Honeywood (1950-2010), Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) and Alma Woodsey Thomas (1891-1978).

Finally, there’s Women’s Trek, a digital print by the well-known illustrator and artist, Al Hollingsworth (1928-2000). As it traces an endless line of comically tall, thin women, attenuated by an extreme, perplexing anxiety as they traverse through a surreal, unknown universe, the thought arises: is this, then,what life is really about?