For a man who’s left a huge body of work behind — which, in turn, generated a massive amount of print — Rabindranath Tagore remains elusively complex. Most educated speakers of the language aren’t unfamiliar with his thoughts, often dressed in baffling symbolism. Yet, when it comes to his art, they sense it’s a seductive quicksand pulling the viewer into an unexplored, rather phantasmagoric unknown.

When the National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, began an online tour of its collection of Tagore’s art on his birth anniversary in May, another curious phenomenon was underscored. Tagore’s writing, barring a few popular pieces, hasn’t really travelled well beyond Bengali-speakers. But his art continues to be rediscovered in other regions for its timeless vitality.

Here was a man who, despite the drawing lessons of his youth, lacked proper grammar. But then, did diligent training ever spark divine fire? Tagorephiles have often mulled over an apparent contradiction between some of his writing and the unsettling shades of darkness his mangled distortions hint at, sometimes sharpened by a macabre humour. Was he baring some tortured angst the savant hesitated to reveal to a society of puny people fixated on a “gurudev”, a role he partly acquiesced in? The mental state that gave rise to one of his last poems, where he despairs of an answer — meleni uttor — had, in fact, laid dark subterranean layers in several of his masterpieces. Having seen death up close, is it any wonder that an elegiac tone would haunt not just some of his writing but also his art?

The art scholar, Partha Mitter, notes, “There were two distinct sources of his modernism: Art Nouveau and Jugendstil graphics and primitive masks and totemic objects.” Although radically non-conformist in his thinking, Tagore wasn’t a proclaimed rebel, sensitive as he was to social censure. Was he then taking the liberty to unleash, in his “primitivist painting” untamed images as a “ludic expression of his inner subjectivity” to get around the stifling burden of iconhood?

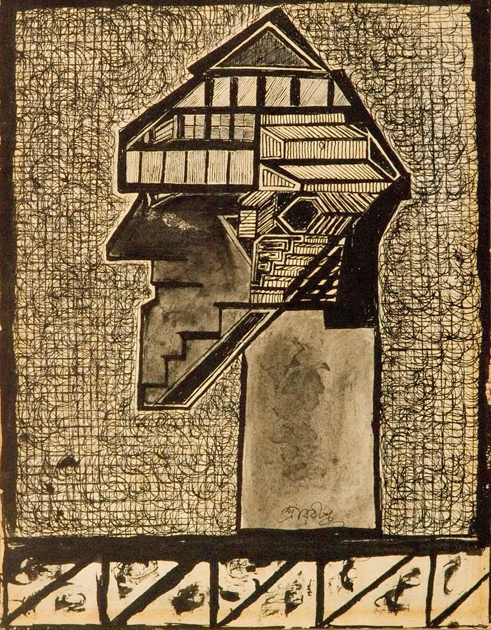

Artwork by Tagore from the NGMA exhibition. NGMA

The timeline NGMA follows links his literary output to the milestones of his life. Dated between 1928 and 1940, the handsome collection is mostly in ink on paper though watercolour in thin layers and quick daubs is also included. Tagore’s mysterious women get talked about the most. But many of the gaunt heads and the sharp, angular contortions in his drawings and paintings are so stark, the forms so beguilingly surreal, the blacks and other dark inks so ubiquitous, they hold a magnetic fascination for the viewer. Of course, the scratchiness of the nib of his pen on his manuscripts had readily yielded bizarre, rectilinear shapes that weren’t as smooth-flowing as those made by a brush. But it’s amply clear that battering the lyrical and the dainty — that’s so much a signature of the Bengal School and sometimes embroiders his poetry — was a matter of choice.

A watercolour head, misshapen as though refracted, a semi-Cubist profile with chiselled lines, fantastic birds and beasts with geometric contours and a staccato rhythm, figures of flowing, calligraphic lines reveal, on one level, a caricatural brevity in exploring subliminal veins of the imagination. On another, there’s the uneasy stillness of Seven Figures, the creeping menace in Fox in the Forest, the bleak, brooding landscapes in pastel and ink. Where is the exhilarating, sensuous wonder of “Akash bhara”? The defiant, uplifting humanism of “Tai tomar anondo”? What takes over is an edgy, irreverent play that may plunge to a gnawing disquiet that renders reassuring certitudes puerile: here is an intimation that the enchantment of life lies in its irreducible enigma beyond easy reckoners of the good, bad and ugly.