For their post-lockdown comeback, Kasba Arghya has produced Nag Nagini Katha, a play based on snake myths and narratives sourced from various civilizations and eras. The human fascination with snakes is primordial; unsurprisingly, ancient myths across cultures are thoroughly snake-infested. Although the actual reptile evokes fear and repulsion in most, snakes in human imagination have been associated with a host of ideas, including rebirth, fertility, healing, sexual energy and spiritual awakening. Nag Nagini Katha chooses to focus on snake narratives built around notions of gender divide and exploration/suppression of female sexual agency and desire.

Given the avowed predilection of the director, Manish Mitra, the performative idiom of Nag Nagini Katha is rooted in Indian theatrical traditions spanning classical as well as folk forms. Mitra is an illustrious name among those attempting to keep alive the practice of Indian theatre by creatively infusing into the body of such theatrical works elements of contemporary global theatre. Thus, exhibiting a snake-like flexibility and shape-shifting ability that the creature is fabled for, Nag Nagini Katha slithers onto the proscenium stage to drape itself in a modern light design, and then raises its impressive Indian hood by completely eschewing the structure of European plays. Episodes, rather than scenes and acts, are the structural units here, and these move along a serpentine trajectory, where the aesthetics of performance and narrative remain privileged over chronological linearity. The play thus glides fluidly from Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay to medieval Cambodia and Karnataka to finally reach ancient Greece via a Biblical detour.

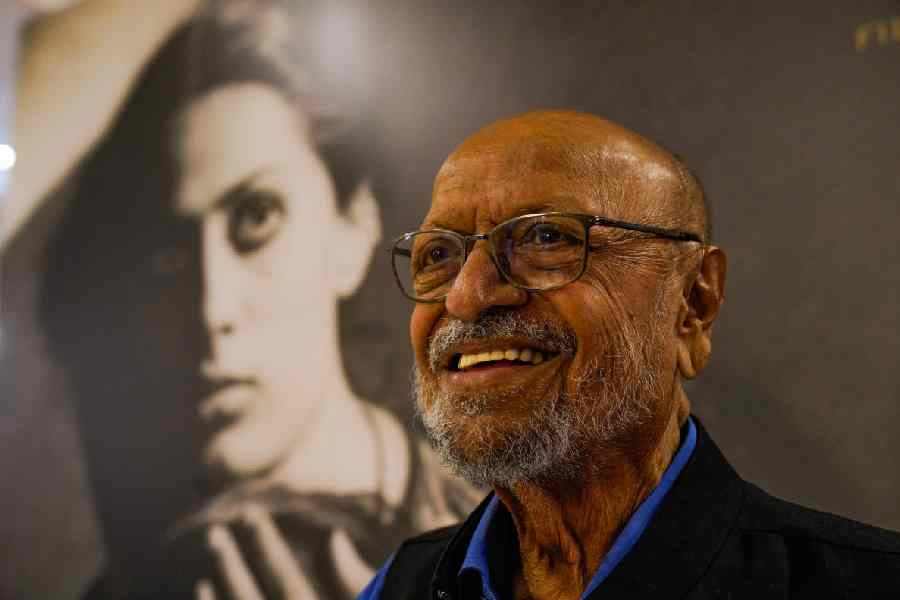

Music in Nag Nagini Katha, as in most Manish Mitra plays, becomes an ambient soundscape cradling the entire performance, fixing its emotive timbre and marking out the dimensions of performance. However, the post-interval musical piece, while falling pleasingly on the ear, seems thematically disjointed. Mitra may wish to revisit some compositions burdened with the weight of mainly static choric figures. While the seasoned Tapas Chatterjee excels in the Khnora/Bibi episode, the find of the play is the young Aishik Roy Chowdhury, whose explosive performance — packed with raw power and lit up with scintillating expressiveness to give life to his director’s vision — speaks volumes of his talent and training.