An obvious fact sometimes bears repetition. Were it not for man-made objects marking time and geographic space, there would have been no past to recover, no community ethos to pass on, no history to reconstruct. The title of a recent show at Nature Morte, Delhi, Markers of Time and Space, reminds viewers of how objects and images transcend their immediate functional role to become clues and cultural signifiers over time.

Few signifiers are as aggressively loaded with trenchant messages as flags are. Or iconic architecture, for that matter, if it symbolizes authority, religious identity or nationhood. That could be why Ayesha Singh sets about upturning hallowed shibboleths with wry irony. Her Flag (Wrapped) is in a no-nonsense grey that would be mournful were it not for the steely sheen to the fabric column referencing industrial construction. In one fold is the printed image of a pillar, rife with metaphorical echoes around the concept of power and its pretensions to permanence displayed in triumphalist monuments. This one comes from Rashtrapati Bhavan, apparently, once the seat of imperial might, and hints at stubborn institutional continuity under catchy — populist — changes that remain cosmetic.

Is that why a bust of Gandhi by Thukral and Tagra has its face turned to the wall? As though Gandhi were disowning the azadi that meandered in directions contrary to his own aspirations for his people, who are left to squabble over his shadow? Or is Gandhi now a cliché and needs to be retired? In any case, Gandhi would have approved of Benitha Perciyal’s tableau, Let Them Own Their Land (picture, bottom), which recalls a forgotten slogan from the 1950s: whoever tills the land must own it. Simultaneously, a diachronic perspective acknowledges agriculture as a crucial marker of civilization for it was the first step towards settled community life, leisure and culture. As it happens, her other work, Why God Won’t Go Away, can be readily read as a burial ritual suggesting incipient metaphysical thought in early man. Interestingly, her use of frankincense and myrrh, apart from other unusual material, invests the lowly soil toiler with a secular divinity.

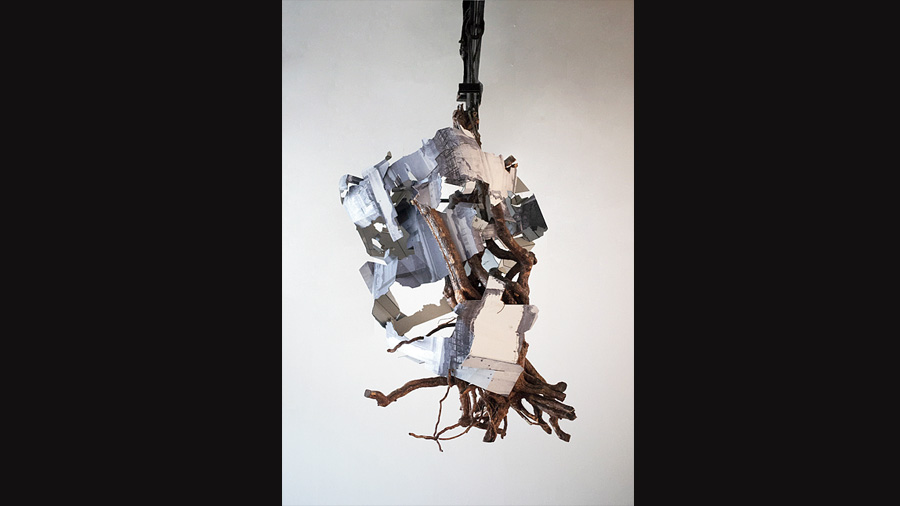

Municipal Demolition 1 by Asim Waqif. Nature Morte, Delhi

Unusual material has increasingly entered contemporary art vocabulary. Like dental plaster that Jitish Kallat moulds for his Antidote with its fruit bat, sleeping upside down, comfortably swaddled in its own wings. Could the work be an extension of the artist’s Infinite Episode? But the unloved outcast of the animal world also brings echoes of the forbidden penance of Shambuk, the Shudra, who lost his head to Ram’s intemperate sword. Ghungroos, although not entirely new as material, is re-invented by Vibha Galhotra to approximate, at least in online viewing, a slithering, treacherous, alluvial bank. Cow-dung, too, is a material of choice for some, notably Subodh Gupta. But in the case of Bijoy Jain, it’s the spry geometry of his bamboo construction that catches the eye.

Suhasini Kejriwal brings Nature centre stage through cactus forms. In Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Emergent III, however, Nature seems to be threatened: her bronze tree could be cringing in fear, with leaves wrapped around the trunk. If M. Pravat’s Granular Structure brings to mind dish antennae, L.N. Tallur’s sickle — the peasant’s tool — interrogates, with its very shape, the violence of its blade. But, as Asim Waqif reveals in Municipal Demolition 1 (picture, top), mauled debris, alluding to violence, destruction and urban waste, can indeed turn into captivating visuals, somewhat like Cornelia Parker’s Cold, Dark Matter. Finally, Anita Dube’s imagination takes flight in a work of elegant, abbreviated levitation: a string of capriciously tangled knots that’s as light as A Bird on a Wire.