Indigenous Indian art is a broad term that has come to include various traditions like those of Gond, Madhubani, Warli to name just a few. While each of these practices is unique, what ties them together is that they are rarely considered ‘fine art’; instead, they are relegated to the margins as craft or functional art. Emami Art’s recent show, Karu — the Bengali word for craft — celebrates these very traditions, highlighting how folk art practices have kept up with the times while conserving long-established techniques.

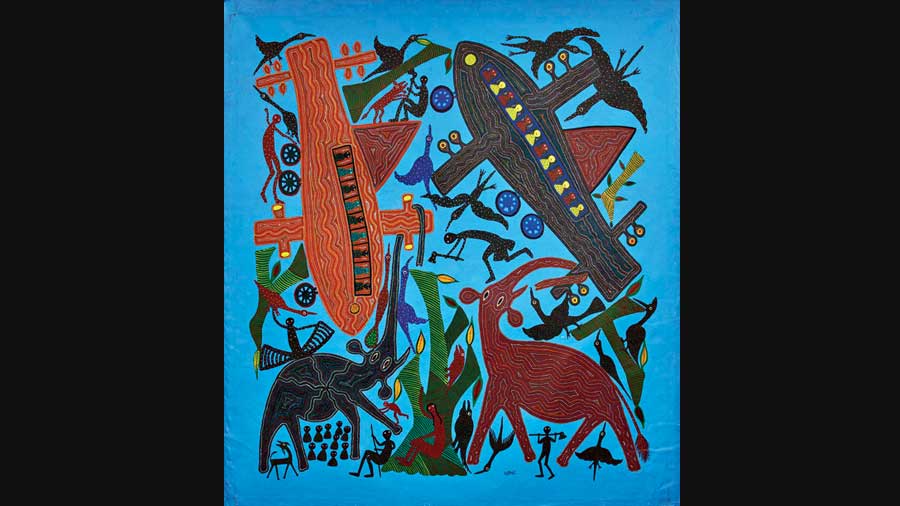

Karu brings together six widely-recognized artists — Bhuri Bai, she received the Padma Shri this year, Akshaya Kumar Bariki, Kalyanmal Sahu, Mohan Prajapati, Nand Kishor Sharma and Ram Soni — who show that tradition is not a static entity but something that, while being connected to the present, continues to evolve. Take, for instance, Bhuri Bai’s intricate, pointillist works (picture): the bus and the aeroplane may have replaced the bullock cart, and her characters may be dressed in formal shirts, but the spirits and mythical creatures that roam through her works echo the Bhil fables of yore. Mohan Prajapati combines the delicacy of style of Mughal and Rajasthani miniatures with a contemporary playfulness of themes and the exquisite sanjhi paper cutting by Ram Soni infuses an environmental treatise into myths. As fine and detailed as this papercutting are the quilt or kantha embroideries done by the skilled women artisans of Bengal, depicting mythical and everyday scenes — unfortunately, the women artists are not named online unlike their more famous counterparts in the show.

The large patachitras by Akshaya Kumar Bariki and the tales of Krishna depicted in the pichwai paintings by Kalyanmal Sahu are dazzling in terms of both complexity and their striking use of colour.