Brisk, nervy jabs of digital brushes conjure up two identical trees on either side of a screen as a child’s voice recites, mechanically, that a certain tree grows in Hindustan. A raucous chorus repeats the line. Soon the multi-channel audio turns it into a shrill cacophony as the trees are replaced by grey clouds. Srinagar-born, Melbourne-based Moonis Ahmad Shah lampoons what he describes as the “taxonomical arrangement of landscapes in the context of Indo-Pak territorial politics”. Such classroom drills could well be a tool to instill a xenophobic pride in separateness negating shared geographic and cultural moorings.

Shah’s video, Material for a Love Letter, was part of In Search of New Names, Experimenter Gallery’s Learning Lab initiative for which 18 applicants, nine each from India and Pakistan, were guided by the Berlin-based Pakistani artist, Bani Abidi, and the Delhi-based film-maker, Priya Sen. The participants, paired for collaborative creative exercises, interacted virtually as they forged enduring ties. Reassuringly, common citizens on both sides — those not brainwashed by official narratives, that is — refuse to abdicate their responsibility of allaying each other’s mistrust through conversations, even as the midnight twins, confirmed in their cold conflict, prefer verbal skirmishes to dialogue.

Yet, for refugees from Pakistan, nostalgia persists. Her nani’s stories about her ancestral home in Multan inspire Pune’s Payal Arya to breathe visual life into Asif Farukhi’s poem, “Samundar ki Chori”, by focusing, via footage sourced from Marvi Mazhar and Alexander Iskander, on fragile reclaimed land in Karachi. While Lahore’s Sundas Shaukat revels in her virtual visit to a Bangalore park via Shruti Chamaria’s video, the latter visits Lahore through the lens of the tour guide, Imran Ali.

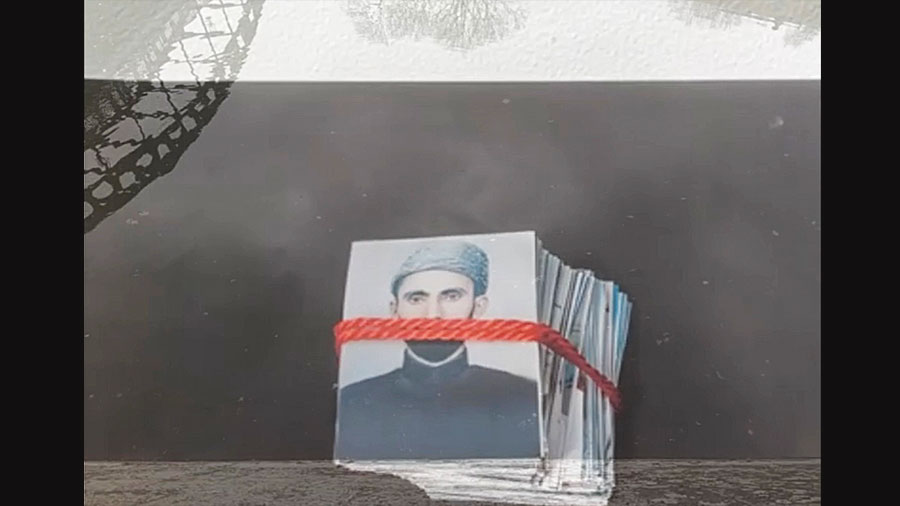

In Prime Real Estate, Assam’s Tahireh Lal splits the screen into a diptych. One half tracks, in staccato rhythm, an exclusive neighbourhood in Karachi to show how the elite in Pakistan lives behind a security wall that her partner, Sarah Kazmi, briefed her on. The other half looks at another wall, one near Lal’s residence: mistrust erects multiple borders within borders. In the video shot by Lahore-based Nida Mahboob and directed by Bombay’s Shilpi Gulati (picture), the camera glides over the Berlin locality the former is living in now, and pauses before a mosaic of a face that looks like George Floyd. It’s captioned, Made to Feel. Made to feel breathless, Black, poor, ignored, unheard, cornered. That, therefore, is also the apt title of the video. As it happens, Mahboob has been compiling documents on how a community in Pakistan has been made to feel alien in their own homeland: the Ahmadiyyas. Dr Abdus Salam’s grave, for example, initially bore the epitaph, the first Muslim Nobel Laureate. Later, the word Muslim was blanked out.

In fact, the othering of some recurs as a motif. Pune’s Aditi Kulkarni learns from her collaborator, Feroza Hakeem, how fear stalks her people, the Shiite Hazaras, in their hometown, Quetta. Hakeem’s camera, following Kulkarni’s direction, pans over the tops of grey, graceless buildings crammed at the foot of grey, treeless hills under the sweep of an uncluttered sky. The stark beauty of Nature is the backdrop to ugly discrimination. Hakeem, photographed by a family member, speaks of their disturbing experiences sitting on an alincha, a traditional mattress used by the community. Has the safety that one’s homeland assures shrunk to the tiny rectangular space of the weave? Baroda’s Pritish Bali reminds us, in Monument to Colonial Amnesia, of a damning othering from history, when Bengal’s poor became dispensable baggage to the British who simply let lakhs perish in the famine of 1943.

Yes, atavistic prejudices seem to have a long reach. Even during a catastrophe.