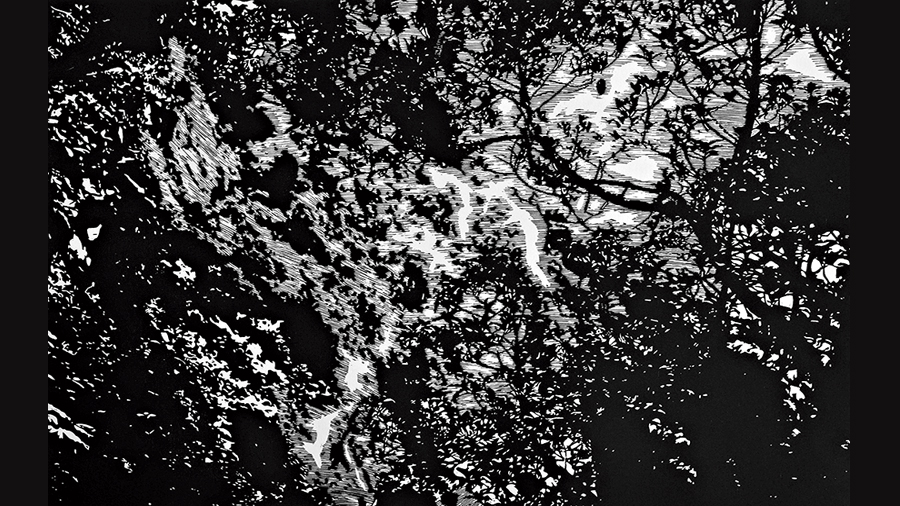

If one scrutinizes Chandan Bez Baruah’s exquisite yet — unlikely as it may seem — politically charged woodcut prints of the seemingly pristine landscape of the northeastern regions of India and reads between lines, as it were, one can easily detect the unmistakable signs of human habitation and depredation even amidst the lushest of vegetation. For beautiful as nature is in these relatively unspoiled jungles and mountains, the latter also bear the unmistakable imprint of this vast region’s troubled and bloody history of sectarian strife, violence and uprisings against subjugation in the past — a trend that continues till our present volatile times.

Unfashionable as landscapes are today, Bez Baruah’s acute political sensibility and awareness of the tumultuous history of the land where he was born and raised, turns nature into a witness of events triggered by human agency. Bez Baruah’s considerable skills as a woodblock printmaker and in creating matrices are steeped in tradition. Yet his sensibility and aesthetics are so alive to the life around him and his personal experiences that he has pushed this medium forward and established its contemporaneity. Bez Baruah’s works of 2019-20 were presented in an exhibition tellingly named If A Tree Falls (Somewhere in the North-East) at Gallery Latitude 28 in New Delhi from January 22 to March 10. It was curated by Waswo X. Waswo. Bez Baruah was born in 1979 in Nagaon, a city in Assam, but it was in Guwahati that he developed a communion with nature and the jungles of the region. He was trained in printmaking at the Government Art College, Guwahati and thereafter at Visva-Bharati. He has travelled extensively through these forested areas and photographed them as well with his digital camera. He uses the digital prints of these images as the opening gambit of his woodcuts, using middle density fibreboard when he worked in Delhi and gamari in Assam, where he is based now. While Bez Baruah uses digital photography as his reference point, the matrix is created by carving an image into the surface of the block of wood entirely by hand with the help of gouges. While these infinitely detailed prints look photorealist, in reality these are landscapes observed through the filter of Bez Baruah’s perception that is moulded by his intimate knowledge of the region’s past and of the lives of its inhabitants.

In traditional landscapes and in Indian miniature paintings the wealth of verdure and the rolling hills as in the wood engravings of Eric Ravillious symbolize harmony. The canopy of leaves are in perfect symmetry. But in Bez Baruah, the bamboo groves, grassy land, eroded hillsides where perhaps the folk gods reside, have been trampled upon and felled or cleared to make way for roads or for agriculture. Landscape becomes a metaphor for the havoc wreaked by man. There are what look like black holes amidst the riot of greenery glimmering in the sun — as if they were the core of darkness that has eaten into this bounty. The striated sky looks calm and serene in most prints, but clouds occasionally denote turbulence — Bez Baruah’s moods colour his perception of nature.

In some prints the hutments and pathways cutting through the wilderness are clearly delineated. But in most, the broken tendrils of vines, the crushed branches are subtle indicators of incursion.