Medieval monastic revulsion for sensuous pleasures led the Benedictine monk, St Anselm, to pronounce gardens as dangerous. Because, well, roses pleased the senses of sight and smell. Yet, to be cast out of the Garden of Eden was the ultimate punishment: the perils beyond an oasis retrieved from the wild by human intervention were truly frightening. By positing Gardens as Thought Form: Lexicons for Revolution, Experimenter gallery (Gariahat) in its recent show of three artists interrogates assumptions of order and beauty through the intriguing and provocative conceit of the garden: the conformism it manifests, the manicured prettiness it embodies and the transgressions that subvert an idyll to repurpose its metaphorical implications.

In the video by the Afghan artist, Aziz Hazara, a small boy perches on the shoulder of a pre-adolescent and plays a war game, imitating the gestures and sounds of an auto-loading gun. Toy guns are legitimate gifts for boys just as dolls are for girls in a socialization process of neat binary order that confirms socially-sanctioned roles. Hence, its title, Rehearsal. But wait. Rehearsal for what, really? For boys being toughened as future killers, no namby-pamby compunctions? An endless wave of violence in Afghanistan makes assault rifles available, visible and aspirational objects for boys who should, ideally, be in or have just stepped out of kindergarten, a significant thought form

devised by Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852). But Afghanistan’s children were robbed of their Eden of childhood more than 40 years ago and remain exiled from it.

His pair of photographs, Chalk Drawings, brings to mind hopscotch, a game of lithe leaps dictated by demarcating lines of chalk. Lines that become as charged as mines in children’s imagination and cannot be stepped upon. Such Lakshman rekhas — whether physical or just verbal and notional — can induce in people total psychological compliance with regimented alignment and approved conduct. To anticipate and nip possible acts of recalcitrance: like plucking the fruit forbidden by no less an authority than god himself.

But what’s forbidden is irresistible to young rebels. In Locations in the Garden of Love by the Pakistani artist, Bani Abidi, the camera glides across parks, a zoo and Jinnah’s mausoleum in Karachi to weave a wry sub-text of ambience, defined as much by the structures as by the visitors and their behaviour. The voiceover of the minders — gatekeepers, park rangers, security guards — superimposed as text on the visual, tells you how these guardians of rules must often contend with deviant, out-of-alignment behaviour.

Like that of two children clambering up instead of sweeping down a slide, as all obedient kids should. But a rebuke to the naughty boy earns the keeper an instant retribution from the girl with him. Yet the bruised victim concedes a grudging admiration for this gesture of fierce loyalty. At the zoo, turtles gifted by the Sultan of Brunei bother the guard, for they openly engage in “doing inappropriate things” for all to see, including, scandalously, an old, devoted couple who visit regularly. But the worst offenders are young couples who use iconic locations like a national monument for frivolous purposes. The white marble of Jinnah’s austere, no-nonsense mausoleum, symbolizing the nation’s reverence for its founder, must denote in its whiteness the purity the land of the pure had sought in the name itself: Pakistan. But is the nation as indestructible as the stone?

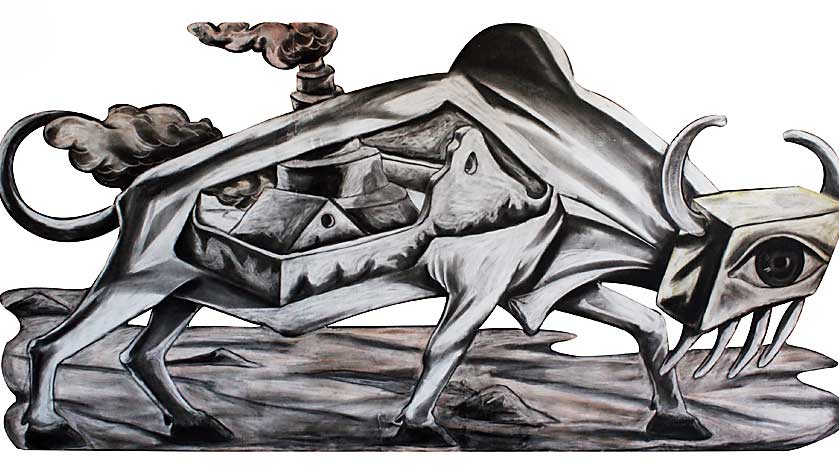

Land, of course, is eminently destructible. Prabhakar Pachpute’s stark, distressing imagery of ashen topographies, dehumanized labour and an emaciated animal, mouth stuffed with tools (picture), warns, once more, that mining is an endgame: options of renewal get gradually erased as its serialized obituary to gardens unfolds.