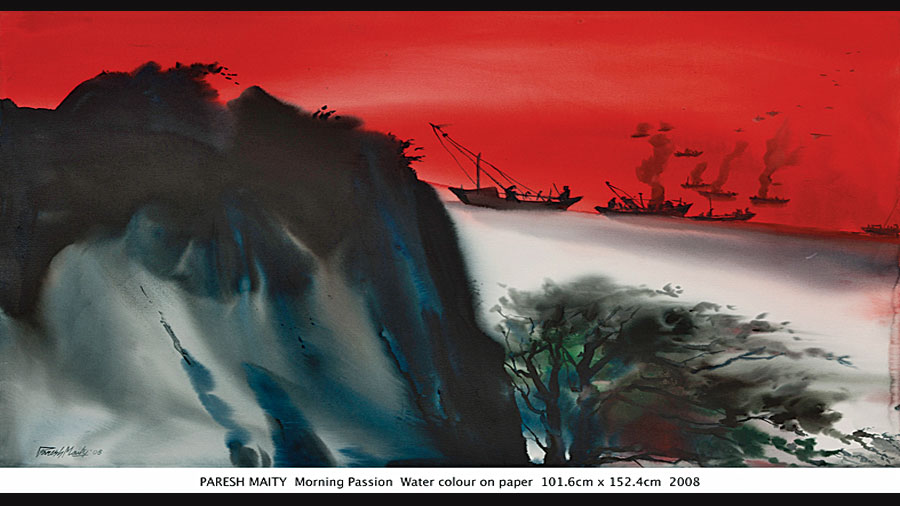

It’s a simple naturescape in watercolour on paper, but Paresh Maity’s technical ease with the treacherous medium makes it stand out. Instead of short, sketchy strokes easy to apply when the size is large — in this case, it’s 101.6 cm X 152.4 cm — the lambent red of the sky tinted with smoke comes in unbroken, unfaltering sweeps. What looms in the foreground is a mound cloaked in coal-black on top that cascades down in shades of blue-grey and slivers of white into undulations. In his other watercolour, the floating blues of the sky evoke breathing spaces.

That’s how CIMA’s Summer Show, on till the end of July, brings in the outdoors away from the lockdown confinement. Similarly with Paramjit Singh’s bristly, tangled strokes in oil, in which untended bushes and patches of rotting pink under a distant cobalt sky seem to pull the viewer into an embrace. And Shreyoshi Chatterjee, who balances the narrow verticality of her canvas with the horizontal segments of her landscape piled on top of each other, takes the eye skipping to the sky at the top. Her Kitchen Diary indicates, in humorous tones, how her play with vegetables and their peel comes from an instinctive affinity with the colours, textures and shapes of the bounty of the earth. But is the earth in turmoil in Yusuf’s canvas as its boulder formations, stippled with ink, disintegrate like fabric across a ground divided into horizontal strips that could collapse like palm leaf patachitras?

The warning is also suggested in Meera Devidayal’s canvas, Mosaic. The first image of her diptych is a flat, parched land receding into a gaseous horizon, on which construction has just started. In the second, the entire area is paved with broken tiles, perhaps the leftover pieces from the unseen buildings that cast rectangular shadows on the piazza. But then, choking the earth gives construction labourers their roti. In mixed media montages, Manish Moitra vividly portrays their toil as mechanical, dehumanizing and, therefore, in cheerless monochrome. Debraj Goswami, in a mix of jest and enquiry, brings Baij’s Santhal Family into the era of the hoisting crane and the tractor in his acrylic, One Step Forward, Two Step Back [sic]. The inference is tempting: over decades, the subaltern remains dispossessed, but for his two arms. And disembodied arms, painted with photorealist finesse, is what Sanjeev Sonpimpare arranges like the movable handles of a machine in Nation State, maybe as a reminder of the role such anonymous arms play in building the nation.

For Veer Munshi, a Kashmiri artist forced to flee his Srinagar home in 1990, the nation could well appear as a wasteland strewn with incendiary Shrapnels [sic]. A man’s head at bottom left in his large canvas convulses in bottled rage and angst, a visceral scream frozen in his throat. A phase in Kingshuk Sarkar’s adolescence was stalked by dread and anxiety in another conflict zone, Assam. That could be why violence, implicit rather than stated, often surfaces in his works, as it does again here with orange and black acrylic seeming to lash out at the canvas in hefty splashes dripping like blood.

Gourishankar Soni’s amused squint at society as a collective of disparate individuals holds the eye as does Shakila’s articulate collage. Abir Karmakar’s portrait of a man with plastic flowers is disturbingly pensive, poignant, while Arpita Singh’s Ocean Dream reflects once again her moving empathy for the utter vulnerability of older women. And if Seema Ghurayya’s inflections in tones of beige are a retreat into meditative reticence, the chatty ebullience of folk dialects — Gond and Pichhwai — remains infectious.