“Kantha art is exclusively a woman’s art form. Bengali women express their desires or colourful dreams by wielding with their deft fingers a needle and thread like a skilled artist’s delicate brushstrokes and presenting variegated designs on a kantha.” So wrote Shila Basak in Banglar Nakshi Kantha. Perhaps this was the idea at the back of Meera Mukherjee’s mind when she engaged the women of Elachi village near Narendrapur, where she cast her bronze sculptures using the indigenous lost-wax process with the help of artisans, to create colourful kanthas under her supervision. This would enable them to generate income by selling their creations. They could save the extra cash in their bank accounts as the first step towards self-reliance. Some of these kanthas created through collaborative effort were displayed alongside the drawings and sculptures by Adip Dutta, who from his teens had been mentored by Meera Mukherjee, in an exhibition titled Adip Dutta & Meera Mukherjee: Nestled (January 22-March 31) organized at Experimenter in collaboration with the Seagull Foundation for the Arts.

Mukherjee in her resolve to get the community involved asked the women’s offspring to do drawings based on which designs were created for the needlework. Mukherjee chose the cloth and the colour of the threads as well. The designs were delightfully childlike, the way Paul Klee was childlike in some drawings. The scenes of everyday life in a Bengal village are simple but the layout is far too sophisticated to be child’s play. The women were allowed to use their imagination through the medium of the running stitch, but under Mukherjee’s guidance. Many of the kanthas were signed. The names Asura and Idan were legible enough. Notwithstanding the exhibition title, Mukherjee was the brains behind the enterprise, but the needlework testifies to the women’s talent.

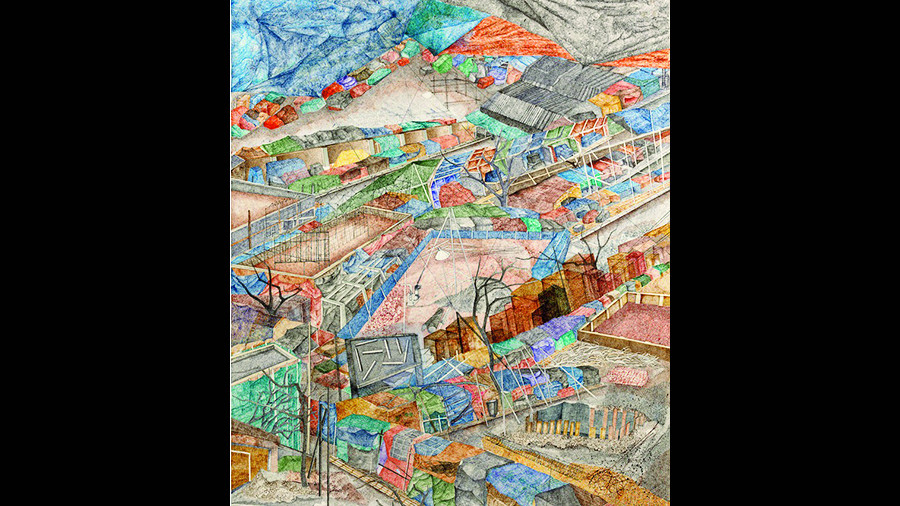

An artwork by Meera Mukherjee. Courtesy of the artist, The Seagull Foundation for the Arts and Experimenter

Adip Dutta has struck out on his own as an artist, but because of the strong bonding that he shared with Meera Mukherjee this was a homecoming of sorts. Mukherjee’s mother and child sculpture suggests that. The two juxtaposed sections have commonalities and divergences. The solitude of Dutta’s drawings is the obverse of the joie de vivre of the kanthas. As in the latter, Dutta eschewed perspectival drawing. Like the kanthas they appear flattened. The dashes, dots and small lines repeated all over the drawings to define volume correspond to the running stitches of the kanthas. After hours, entire stretches of desolate pavements — dug up, pockmarked and cratered — appropriated by hawkers are lined with neat bundles of their stock-in-trade covered with plastic sheets. They are stacked on the pavement or on the benches used to set up shop. Dutta maps this topography of desolation through his minutely observed drawings.

The pavements are barricaded with rails, sections of which have disappeared leaving behind huge gaps. In the foreground is a forlorn tree with its outstretched branches. Dutta has cast an entire tree trunk in bronze and displayed it in the pit amidst the gallery. It is quite as dead as the rest of the scene. In the larger drawings, Dutta created a veritable maze of shops and rails, and, for a change, he has coloured separate sections with softest shades of peach, brown, ultramarine and turquoise that one could associate with Mughal miniatures. The contrasting shades add to the nightwatch drama.