Those who chanced upon Abhishek Hazra’s four-film installation that was on at Experimenter (Gariahat) in October would have needed to keep their thinking caps and search engines ready and raring. To field, fathom and filter the shower of references, ideas and metaphors — including a few googlies — thrown at them with deadpan mirth. Not with earnest application, brows furrowed, but with free-spirited smirks that match Hazra’s cerebral wit and underground banter, peppered with concerns anchored to a background score as astutely devised as the sharp, often enigmatic text and the blitzkrieg of visuals, wired with teasing suggestions.

Bengali literature and political philosophy, the problematic measurement of labour in Grundrisse and the termination of all measurement in the heat death of the universe, old-fashioned catch phrases like dialectical materialism (here, diamat) and new-age buzz terms like post-colonialism (here, PoCo), imperial pageantry and the Naked Fakir’s dispossessed land, country ballads and a seductive musical passage from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, with hectic, galloping drums and a raucous voice: Repetition and Reticence takes you leaping breathlessly from excerpt to idea, from image to allusion, from sense to sensation, spurning linearity, but emerging with gestural logic.

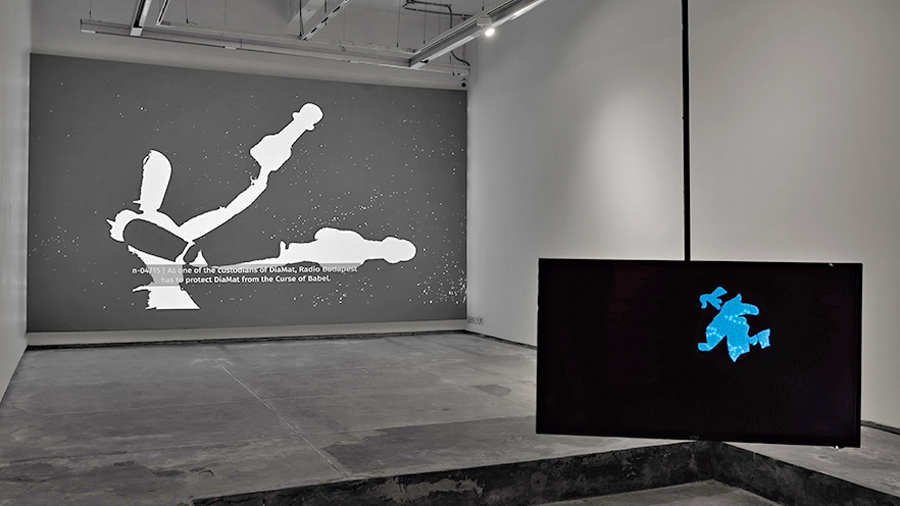

As tensile, blue, Mattissean cutouts slip and skip out from a fluid black with patterns fluttering across, he fires a polemical salvo about Meghnad Saha, held up as a symbol of class/caste marginalization. Like Ambedkar. Hazra focuses on how the scientist chose a mythological name deemed heinous in dominant majoritarian beliefs, but heroically defiant to rebellious sceptics. Which is what Michael Dutt was in celebrating in his kavya, a tragic rakshash protagonist who took on a god. Its subversive intent is hallowed where its lines seem to appear like street graffiti, but across the sky.

The “Deltaic Renaissance” gets stinging sidewinders for its inability or unwillingness to upturn the “graded verticality” of society. It burdened Saha with birth-inflicted handicaps that would even have, says the artist archly, throttled Shakespeare had this son of a glover been born in Bengal. But then, ironically, would the Left-leaning non-believer, Saha, have found any spark in Bengal comrades after 1979? After all, can one differentiate between the imperialist violence unleashed on the Odessa Steps and the Marxist violence unleashed on Marichjhanpi settlers?

The “marriage” of an electron and a positron in the third film — visualized as flickering grids, graphs and shapes — is solemnized to the strains of the shehnai. Since such a union leads to the “beauty” of annihilation — so complete is their self-destroying oneness in each other — he concludes that it’s both suitable and a grotesque puzzle. No wonder this marriage invites a comparison: the one between hammers — to drive home a point? — and the “verbose Bengali institution of adda”.

Then comes a reference to Hungary, 1956, when the radio station was a flashpoint in the rebellion. Hence, in 1957, Radio Budapest, now “a custodian of Diamat”, switches to the “automated translation” of its messages into languages like Bengali to ensure their “uncorrupted propagation” because human translators were seen to be “infected” with the “curse of Babel” — obviously pluralism — that could trigger “self-contradictory disasters like 1956”! As stimulating is Hazra’s performance while he narrates how he rediscovered, through Meghnad Saha’s calibrated understanding of Thermodynamics, the “Scientific Marx”.

Leaping to the Poona Pact, he terms Gandhi’s fast “moral blackmail dressed as atonement”. Tagore, visiting Yerwada prison, sang “Jiban jakhon sukae jae” for Gandhi. The song is sung here by three voices in disharmony. As a chastening finale, a dirge. Not on Gandhi but the slain epic hero, Indrajit. And that brings us back to the beginning. To Meghnad: the repetition of a leitmotif; interspersed with the ellipses of reticence.