Trained in Santiniketan by masters such as Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee, A. Ramachandran’s mastery of draughtsmanship is demonstrated in his exhibition, A Lifetime of Lines (July 21-August 13), organized by Vadhera Art Gallery, Delhi. The influence of Indian classical art and Nandalal Bose is clearly visible in this exhibition, which bears testimony to the artist’s wide range of interests from figurative to portraiture and extending to satire. Ramachandran (born 1935) is from Kerala, and although his robust drawings of voluptuous Bhil women — often in poses typical of women depicted in ancient Indian visual arts — and lotus ponds may be largely decorative, his disturbing drawings of headless human figures and caricature-like depictions of corrupt and corpulent Indian politicians from the 1970s bear evidence of his strong political awareness. He makes no bones about expressing his opinion on fascism and State power in his deft sketch of the hand being crushed by a hatted jackboot and the black predatory owl.

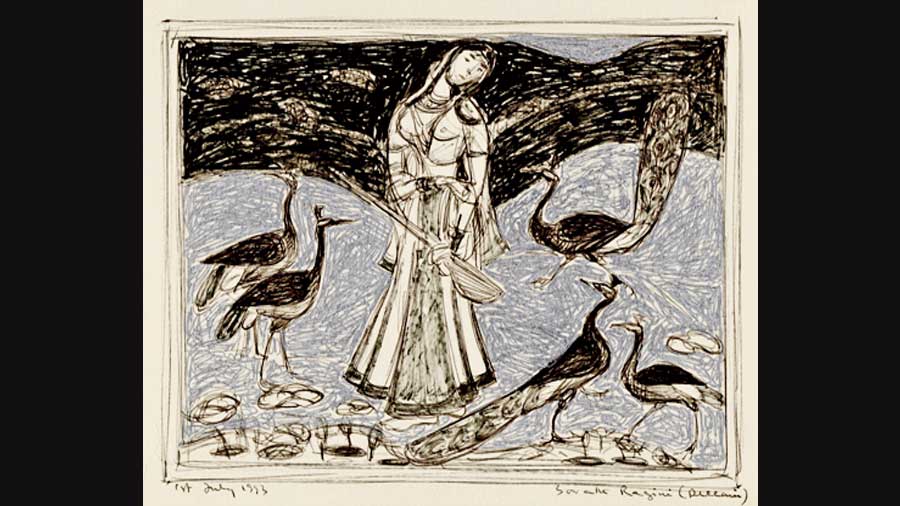

Ramachandran has the tremendous ability to laugh at himself. He does not hesitate to project himself as a mythical, anthropomorphic creature with a mask-like moustachioed visage wearing a halo of unruly locks. Many of these works on paper were preliminary drawings for his paintings executed on an epic scale. These drawings teem with animal life (picture, left). The tiniest insects are as keenly observed as the hefty, snorting bulls, street dogs and comical pelicans and smaller avian forms. Even when Ramachandran’s drawings are sketchy and swiftly executed, they are animated by a rhythm that one discovers in classical Indian art.

Running parallelly at the same gallery was a group show titled, Call Me by Your Name, conceptualized by the art collector, Udit Bhambri, featuring eight leading Indian contemporary artists. The concept note could well be summed up as “Love in the times of Corona”, although the exhibition is meant to explore more complex relationships than romantic feelings at a juncture when social distancing has become the norm, or is expected to be so.

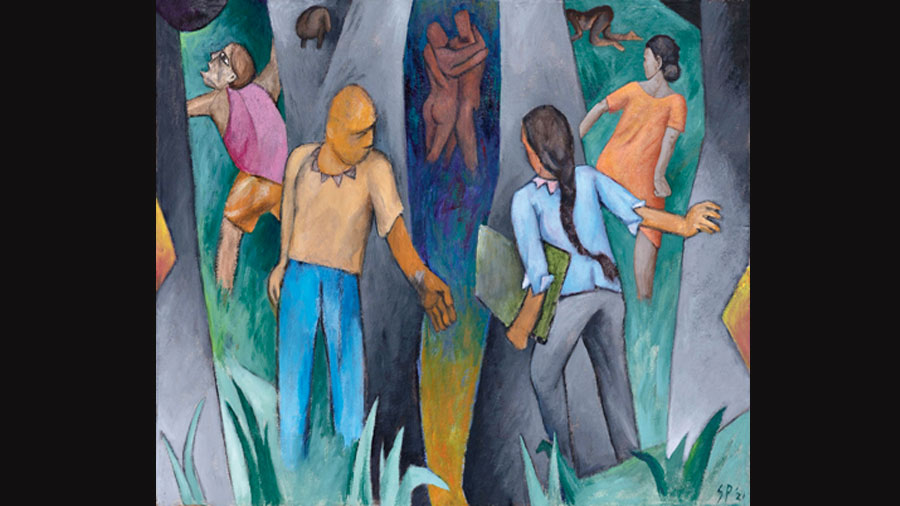

Forest by Sudhir Patwardhan. Vadehra Art Gallery

Sudhir Patwardhan’s stark pastel drawings and paintings (picture, right) make the issue of alienation obvious enough through its depictions of couples who are close to each other yet separated by some invisible barrier. Arpita Singh achieves that in a rather strange way through her watercolour of two little birds reminiscent of a painting of a night heron in the Dara Shikoh album meant for his wife.

Even more curious is Atul Dodiya’s enigmatic image of copulation that becomes a tangle of limbs. The couple is faceless and the watercolour is grey on grey, yet it is clearly modelled on ancient Indian erotic miniature paintings or even religious art where physical union is used as a metaphor for spiritual bonding. Of Anju Dodiya’s two paintings, Tree Lover makes oblique references to the Daphne, the Naiad nymph of Greek mythology who metamorphoses into a laurel tree on being pursued by the god, Apollo, as well as Chipko, the famed forest conservation movement.

The relationship between man and nature is examined in N.S. Harsha’s quaint painting of a pumpkin creeper with a farmer couple as marginalia. Sunil Gupta’s two black-and-white photographs shot in 1983 effortlessly capture the poignance of those times before the abolition of Section 377 of the IPC. Gieve Patel explores the longing of the deprived and Shilpa Gupta several degrees of separation.