Morning has broken. Bob Dylan has spoken. Like he was you and me, a brooding 79-year-old who thinks of today’s world pretty much the same way all sane, regular people do. Horror-struck, shaken, surprised, pensive, resigned, angry, sad, reflective or at times engulfed by this plain, staring-at-the-sunset blankness. He writes. He sings and helms a great band. We know. Why, he even loves the Eagles, the Rolling Stones and some early Miles, although improvisation is not really his thing! We didn’t know.

He has a new album out, the first one of original songs since the 2012 Tempest. May be that’s why he’s talking again. But only to long-time friends and acquaintances, that too at intervals running into multiples of years. His most recent conversations, with Rice University professor of history Douglas Brinkley, excerpts of which were published in The New York Times the other day, reveal a man in pain, depressed even, clearly and utterly traumatised by the unfolding events in his home country and the world. He said it “sickened him no end” to see how George Floyd was tortured to death. “It was beyond ugly. Let’s hope that justice comes swift for the Floyd family and for the nation.” The pandemic, he believes, must be allowed to run its course; for “it’s a forerunner of something else to come… Extreme arrogance can have some disastrous penalties.”

You’ve “gotta serve somebody”, he had sung about such arrogance. Will he write a new song for the many George Floyds of the world? Why, he has written about them before. In the avatar of the protest singer in the ‘60s and ’70s, he sang with pent-up rage about the travesty of justice, racial hatred and token incarceration.

Sometimes I think this whole world is one big prison yard.

Some of us are prisoners.

The rest of us are guards. (George Jackson)

How can the life of such a man

Be in the palm of some fool's hand?

To see him obviously framed

Couldn't help but make me feel ashamed to live in a land

Where justice is a game (Hurricane)

Oh, but you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears

Bury the rag deep in your face

For now's the time for your tears (The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll)

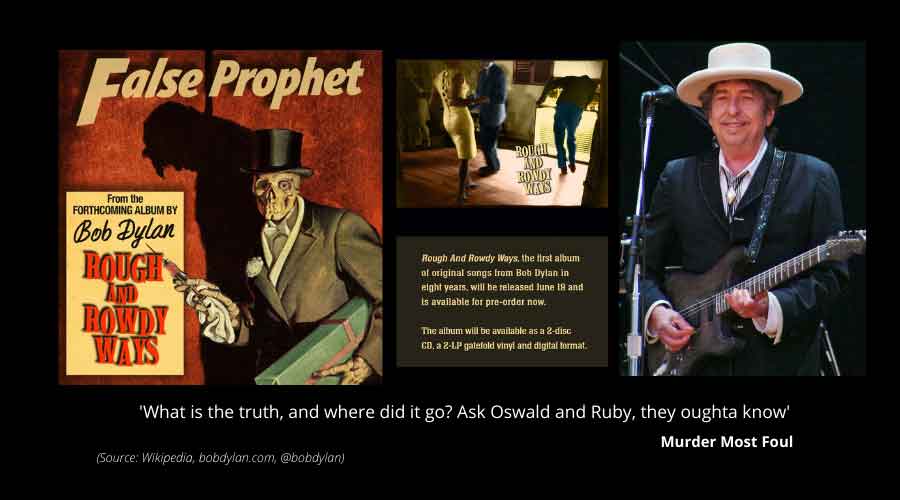

Today, Robert Allen Zimmerman, aka Bob Dylan, finds himself back to where it all started. Murder Most Foul, a 17-minute ballad about the Kennedy assassination is no nostalgia indulgence, he says. It speaks to him in the present moment. Just as the old songs do. That’s because, he says, he “sleeps with life and death in the same bed (I Contain Multitudes)”. Well, you and I are doing the same thing, right? With locked down mind spaces, navigating a quotidian existence with fear and foreboding. Somewhere, sometimes kindness and empathy raise their hands, like a tentative schoolboy unsure of the answer to the question his teacher has just asked him, only to be smothered down and locked in tight.

Dylan resurrects Anne Frank, Rolling Stones and Indiana Jones, all in one song. A young girl of unbridled courage, a rock n’ roll band that’s been playing since eternity and a fictional adventure junkie made real by the symphonic sublimity of John Williams music. “Her story means a lot. It’s profound. And hard to articulate or paraphrase, especially in modern culture,” he says about Frank, the diarist of the Holocaust who died when she was 15. He says he likes the Stones Angie and Wild Horses — what’s not to like? — and the lead man of the movie made real by its score. “The names themselves are not solitary. It’s the combination of them that adds up to something more than their singular parts. To go too much into detail is irrelevant. The song is like a painting; you can’t see it all at once if you’re standing too close. The individual pieces are just part of a whole.”

Like many of us, technology and AI-infused robots on the shop floor worry him. But the reality is that teenagers of today have no “memory lane” to fall back on. And so, decades later when they are in-charge they’ll do it their own way. “As far as technology goes, it makes everybody vulnerable. But young people don’t think like that. They could care less. Telecommunications and advanced technology is the world they were born into. Our world is already obsolete.”

Does that mean good is obsolete too? While discussing Little Richard, who Dylan says, lit a match under him, he dwells on the power and affirmative intent of gospel music, contrasting it with the world’s obsession with “good-for-nothing news”, a phenomenon he blames today’s media for. “Good news in today’s world is like a fugitive, treated like a hoodlum and put on the run. Castigated. All we see is good-for-nothing news. And we have to thank the media industry for that,” he says.

For the many of us who have spent our insignificant lives following Dylan’s poetry and music, we have obsessed about his many ways. We soaked in his boyish charms as he went about asking questions, the answers to which were blowing in the wind. We bought into his self-perpetuated protest singer myth, heard in his song the stories we wanted to hear. We needed a symbol, and we thought he had allowed us to choose him. When he saw Saint Augustine, in his 1967 album John Wesley Harding, and re-embraced his Christian roots with Slow Train Coming in 1979, many of us sneered at his born-again resurrection. Others derided him for having dared to sully our precious memories of him as the troubadour. But the truth is, Dylan was done leading a life for us. He sang for Pope John Paul II because the Church wanted him to. He hawked The Times They Are A Changing for use as a jingle and played for corporate dos. He did it on his own terms, followed his own path. Robbie Robertson of The Band, his one-time collaborator, recalls with affection how nights of serious booing wouldn’t deter Dylan to stop. Guys, we were great; Let’s play louder next time, he would tell Robbie, whose initial befuddlement ultimately gave way to inner belief that what they were doing was indeed great.

Dylan betrays this spark within while describing Robert Johnson, the American blues guitarist whose recordings of the ’30s have influenced generations of musicians. “Robert was one of the most inventive geniuses of all time. But he probably had no audience to speak of. He was so far ahead of his time that we still haven’t caught up with him. His status today couldn’t be any higher. Yet in his day, his songs must have confused people. It just goes to show you that great people follow their own path.”

In these days of long, black clouds coming down, Dylan is content to be able to knock a few fresh punches. Knock-knock? Heaven’s Door is now his signature brand of whiskey launched in 2016, making him one of two Nobel laureates to be personally associated with a spirits brand — Winston Churchill being the other has a Pol Roger champagne to his name. With his album of new songs, Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan is painting some more. We’d better not stand too close. Or else, we’ll miss the big picture.

Train wheels are runnin' through the back of my memory

When I ran on the hilltop

Following a pack of wild geese

Someday, everything is gonna sound like a rhapsody

When I paint my masterpiece

A consummate performer, Dylan has been unspooling the old tapes and playing songs of yore in his concerts over the last few years, acknowledging “there must be some way out of here” even while holding out warnings of “wildcats growling” and “wind howling”. When I Paint My Masterpiece is among the timeless ones that, he notes, has grown on him. “I think this song has something to do with the classical world, something that’s out of reach. Someplace you’d like to be beyond your experience. Something that is so supreme and first-rate that you could never come back down from the mountain. That you’ve achieved the unthinkable.”

Will Dylan write a song on the pandemic and its fallout? On people dying, on people losing their jobs, on millions of forgotten people walking miles on end to get home because they’ve suddenly been cast aside? Or may be on the importance of remembering? If he does, it will be another painting with the same colours he’s been using his entire life. Bruce Springsteen likes to think of him as the “father of my country”. At a time when we seem to have forgotten ours, it’s the eternal quest for that masterpiece we’ll need to hold on to.