CIMA’s celebration of its 30th anniversary continues with the second part of its 12 Masters show — Neorealism to Social Realism (on view at the gallery till March 1) — which features the works of Bikash Bhattacharjee, Jaya Ganguly, Jogen Chowdhury and Meera Mukherjee. Meticulously curated, the viewer stepping into the gallery is given a preview of the works of all four artists, a ready reckoner of sorts, into their styles and the predominant themes that occupy them. Badal O Diner O Pratham Kadam Phul by Bikash Bhattacharjee, for instance, perfectly encapsulates not only the closely observant nature of his realist oeuvre but also his fascination for Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro by using several dark shades of the same colour. His insightful portrayal of women — he found beauty in their tenacity — and the influence

of Tagore and Santiniketan are evident as well.

Bhattacharjee was profoundly affected by the turbulent Calcutta of the late Sixties and early Seventies and Doll, from his famous series of the same name, captures his eerie ability to communicate the fear and the dread of those turbulent times. This unsettling realism is tempered by the poignance and the poetry of the Dekhi Nai Phirey series which comprises Bhattacharjee’s illustration of Samaresh Bose’s novel on Ramkinkar Baij. The young Ramkinkar conjured up by Bhattacharjee (picture, left), using simple graphite sketches and watercolour washes, reflects a wonderment with nature, an element that is synonymous with Baij.

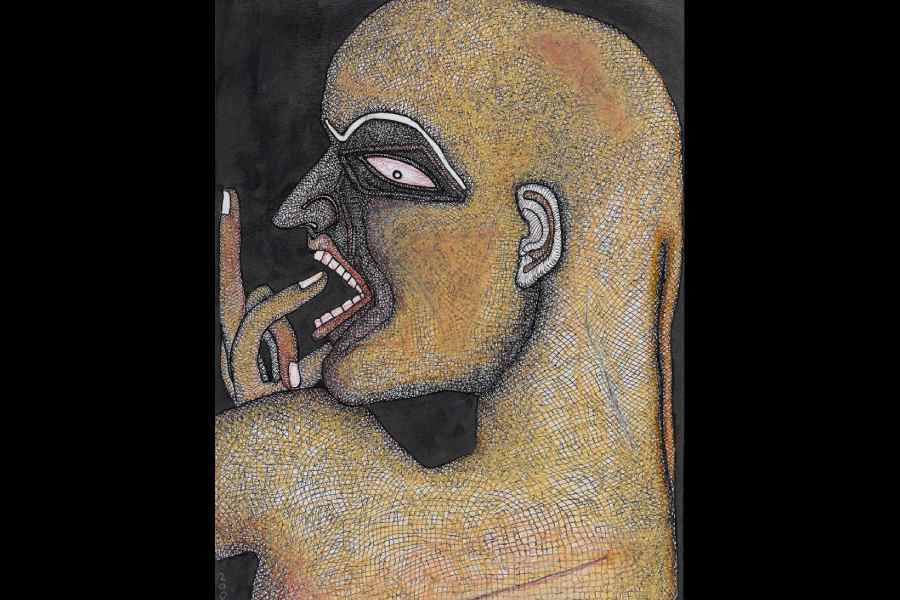

Face in Agony by Jogen Chowdhury Photo courtesy: CIMA

Poetic lines are also the signature of Meera Mukherjee’s sculptures, of which Woman Breaking Husk is the perfect example. Characterised by their rich surface textures and dynamic forms, her sculptures depict individuals or groups engaged in a range of activities, from weaving, rowing a boat or construction work, to protesting, playing an instrument, travelling in a bus or simply reflecting as in Kobi Sukanta Reading a Book. Her sculptures are animated by the techniques and the energy derived from dhokra and other tribal traditions and, yet, have the classical lines of the Chola bronzes and Ellora’s cave murals. The environmental warning in her bronze Ganga also reflects her prescient vision. Mukherjee’s works emphasise the way in which the exploration of both form and humanist ideals fuelled creativity in the age of classical Indian modernism.

Such humanist ideals often stem from deeply personal traumas and a first-hand experience of human suffering as in the case of Jogen Chowdhury. His works cannot be bracketed under one theme, but almost every canvas shows signs of angst. In his hands, the human body becomes the means of expressing collective trauma that

is experienced at all levels of society (picture, right). The recurrent theme of gruesome wounds and mangled limbs in vividly painted images of severed fingers or that of a nude body with a gash across its torso portrays the agony. Disturbing, yet riveting, these images are a powerful comment on our country’s recent history. From the works on display, one could also discern the evolution of Chowdhury’s distinctive cross-hatching, which he uses not only to mimic the texture of human skin but also to add depth and tonality to his works.

The tones of Jaya Ganguly’s works are also dark and predominated by black (in the early stages of her career that is all that she could afford). The darkness of tone and the dominance of one colour notwithstanding, there is no dearth of details in Ganguly’s portrayals that explore the origami folds of the female anatomy. She distorts human form till they become near-caricatures. However, it is not the form that she is satirising but society’s way of looking at that form. By stripping the human form of an idealised veneer of beauty, Ganguly not only dissents against the conventional norms of figurative art but also makes her characters real and relatable. Ganguly’s paintings have a strong graphic quality and her lines carry the conviction of one who knows her mind.