The exhibition, Scenes from Santiniketan & Benodebehari’s Handscrolls (May 20-June 20), at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity acted like a time machine as viewers were transported to those days when the university township was nature’s domain. The exhibition brought together 13 of Benodebehari’s works, all of them were high-quality reproductions save for its pièce de résistance — a 44.6 ft-long original paper scroll named Scenes from Santiniketan. The latter was discovered recently. The exhibition was curated by R. Siva Kumar and it was organised in collaboration with Gallery Rasa.

Benodebehari Mukherjee (1904-1980) was born blind in one eye and was severely myopic in the other. He joined Rabindranath’s experimental school, Patha Bhavana, when he was 13 and was among the first batch of students of Kala Bhavana established in 1919. The red laterite soil of Bolpur, the Khoai with its maze of ravines, the Kopai river, sal forests and Santiniketan’s austere ecosystem moulded his creativity.

Benodebehari was also deeply attached to the art of China and Japan, although, as Siva Kumar writes, he had “indigenized” and “internalised” these influences. So landscapes dominated Benodebehari’s oeuvre and his early years, and his preferred medium was the scroll that allowed him the freedom to contemplate the vast expanses of undulating countryside where human presence was negligible. His self-portrait in the studio (circa 1933) and a detail of his Cheena Bhavana fresco, Life on Campus (1942), testify to Benodebehari’s reclusive nature.

The 44.6-ft scroll began with the view of a tree and its dense tangle of aerial roots. This could have been Chhatimtala once. Deep within its verdant recess is seated a solitary figure, conjectured to be the artist himself. An enlarged image of this section was displayed.

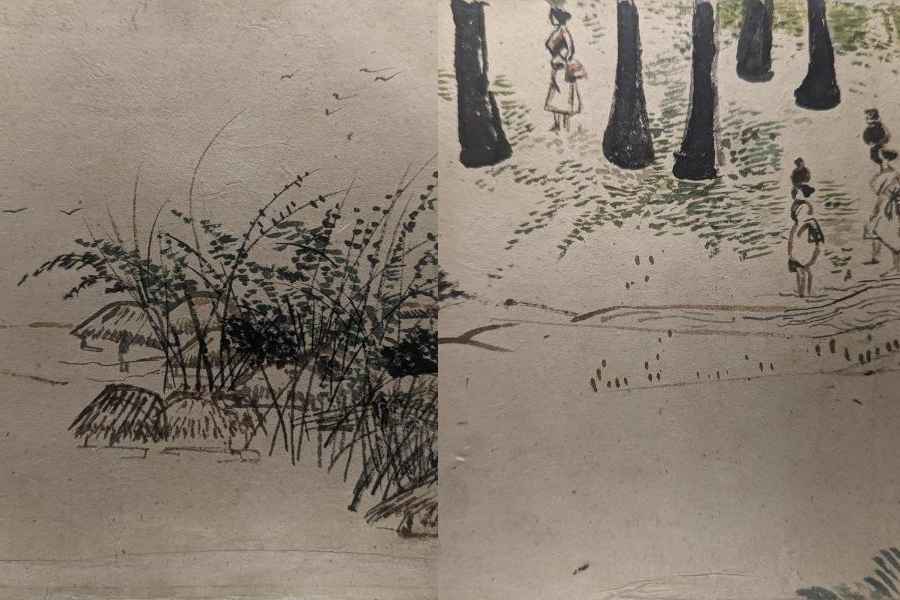

As the viewer’s eye travelled leftward, scanning the flat and barren land, clusters of humble hutments with villagers engaged in their daily chores alternated with sal forests and tall palm trees, paddy fields, bamboo groves like aigrette (picture, left), the river with women fetching water in pitchers (picture, right), and clumps of tall grass that ultimately blended with the Khoai where nature was immanent. The

transition from one habitat to another was marked by gaps on the cheap paper surface. Benodebehari executed it in around 1924. Alongside the shifting geography, the rhythm of seasons was suggested. The black ink used initially turned brown in summer and green during the rains. It is amazing that Benodebehari could pack in so many details, his impaired vision not withstanding.

Then came the two fragments of cloth with sal forests painted on them. In one, the ground was brightly lit. Shadows had crept in on the other.

There were two other village scrolls depicting thatched huts and their occupants on mounds of chrome yellow under the shadow of green trees. These are all from the 1930s. The colours notwithstanding, the rural life depicted here and in the other scrolls, including a fan-like one painted on banana pith (the original of the 1940-42 period is in the V&A Museum, London), was almost identical. The Khoai’s severe beauty stood out in the eponymous scroll.

In contrast to the solitude of the scrolls, the 1940 painting on the Kala Bhavana ceiling, Birbhum Landscape, is a field full of folk. A blow-up of its photograph taken in the early 1940s was displayed as a canopy. The exhibition terminated with Pages from the Chinese Sketch Book.