Chua Chandan, produced by Thealight and directed by Atanu Sarkar, dramatizes Rakesh Ghosh’s stage adaptation of Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay’s short story with the same title. The narrative is temporally located in 15th-century Bengal, when a blustery gale of socio-religious reforms was sweeping across the land stirred up by Sri Chaitanya, who is a central character in Chua Chandan.

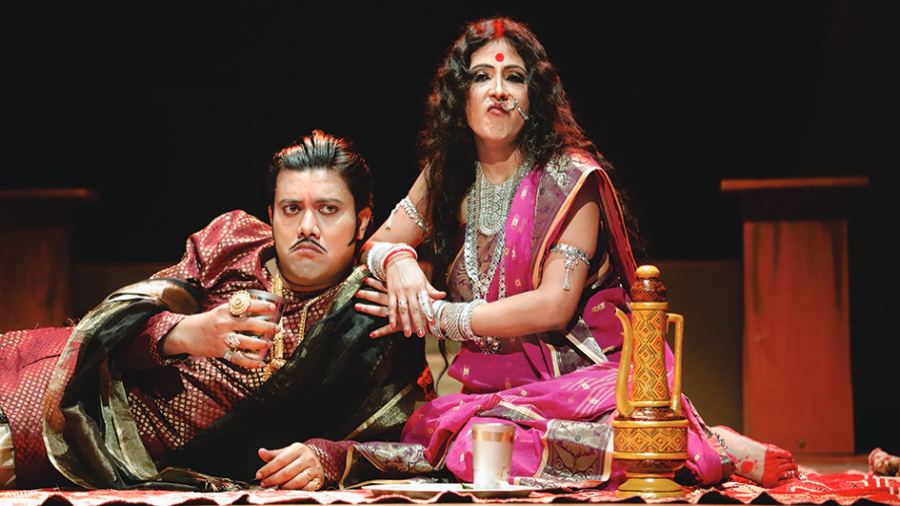

In his adaptation, Rakesh Ghosh has taken the liberty of adding characters, altering key plot points and attempting generally to reorient the gender politics of the original text. The women in Ghosh’s play have a markedly enhanced presence compared to Bandyopadhyay’s story. Responding to the heightened demand of the text, the female actors turn in very competent performances. Sampa Das Sarkar as Champabati deserves special mention — her thoroughly loud and garish characterization is entirely textually motivated and her being able to pack her demanding performance with unflagging energy is quite commendable.

Rajib Bardhan as Chaitanya impresses with his crisp vocalization and a body language that is able to project the tension of his character, whose steely resolve is undermined at times by spasms of self-doubt. While Sandipan Chattopadhyay (Madhab) tends to become overly theatrical on occasions, Debabrata Das as Chandan is a major let down. Chandan is not merely a moonstruck lover, but a successful voyager and maritime trader — Das has focused so much effort into bringing out the lover that other aspects of the character have remained unexplored.

As the director, Atanu Sarkar has used the resources available to him quite well. An aspect that requires reconsideration is the very clumsy scene transitions that impede the narrative flow; Sarkar may wish to find ways of giving to the episodic structure of his play a serious reworking to make it more connected. Finally, not tying up the putrid corruption of Hindu Brahminical practices of medieval Bengal with the contemporary emergence of a fanatical Hinduism is an opportunity lost for theatre to be politically interventionist.