Stepping into the huge exhibition space on the ground floor of Emami Art, one is enveloped by the soothing, anodyne and ever-changing hues of eight of the 50 lotus ponds — captured at various times of a day and mirroring the cycle of seasons — that A. Ramachandran had painted with oils over the last 35 years on huge canvasses. These were part of the Santiniketan-trained artist’s exhibition, covering two floors of the gallery and titled Songs of Reclamation: The Art of A. Ramachandran (ending today). The show included sculptures, impromptu portraits and illustrations for children’s books and was curated by R. Siva Kumar. Considering the vast dimensions of these canvasses, this is indeed quite a feat for the ageing artist (born in 1935 in Attingal, Kerala) who is gradually losing his vision.

Ramachandran is a man of literary and musical talents and he joined Santiniketan in 1957, drawn by the dynamism of Ramkinkar Baij’s work. He moved to Delhi in 1964 and the dark and disturbing works of those times reflect the political turmoil of the period.

By the 1980s, however, Ramachandran had made a remarkable volte-face. He began retelling ancient myths in his own way. Harking back to the Ajanta and Kerala murals, bejewelled and sultry Yakshi-like Gadia Lohar and Bhil women appeared in his art. The deprivations suffered by these indigenes were cloaked in kaleidoscopic colours — they were untainted by reality.

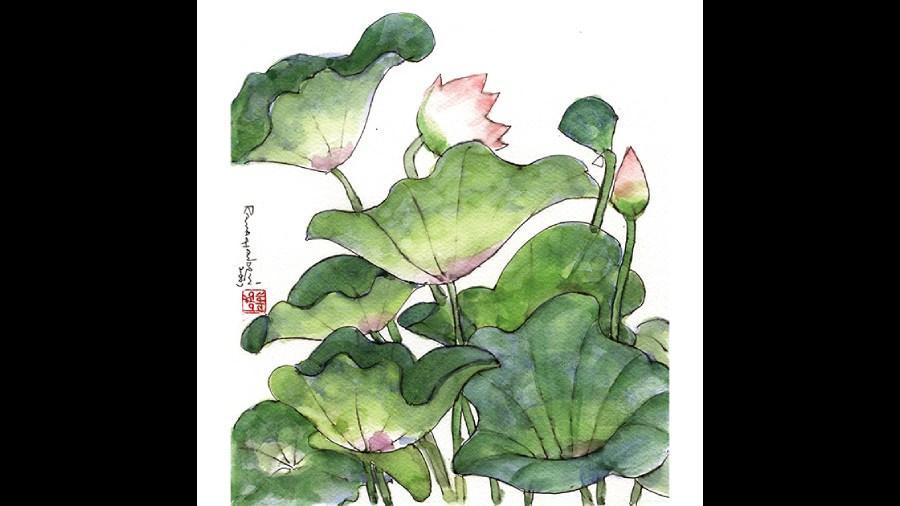

Ramachandran is a skilled draughtsman and he is blessed with a keen power of observation, not missing out a single water plant that forms the layer of aquatic vegetation carpeting the surface of waterbodies, small birds that come in search of food, and insects and bees that hover over acres of flora, all in keeping with the finest traditions of Sanskrit verses. These are like miniature paintings blown up, every detail captured with the unerring brush of a brilliant illustrator and designer.

Ramachandran has a palette of lush and velvety shades. The slender aquatic reeds are outnumbered by the pink blooms of the lotus and their large round leaves in a contrasting shade of viridian. Smothered by wild grass, the flower turns a more delicate shade of pink and its leaves cyan with a core of tangerine yellow in another panoramic canvas. As lemon green water hyacinths choke the lake, in the next, the leaves turn viridian blue with an inner glow of ochre that turns orange. As the lotus pond starts drying, the leaves fall into the sere. The dominating tone becomes a pallid saffron with hints of green. The seedpods, sans petals, swoon on drying stalks, attracting an invasion of insects. In another view of the arid season, the drying plants are ochre and the water emerald. A lone water fowl rises from the jungle of reeds.

With the rains, the sap of life rejuvenates this ecosystem once again, and the monsoon wind causes a flutter in the lotus pond. On a star-spangled night, the bed of leaves becomes the colour of dried saffron washed over with a shade of green.

In the show’s catalogue, Siva Kumar writes that Ramachandran in the mid-1980s used to visit Bhil villages in Udaipur, and these had lotus ponds. Benode Behari Mukherjee, too, painted nature. But, as K.G. Subramanyan wrote, “his paramount interest [was] the plain and palpable world unvarnished by any mythology or romance.” Quite the opposite of Ramachandran, who exoticised the bleak world he saw around him.