The slow revelation of layered nuances possible in a two-dimensional medium like painting is perhaps being rediscovered by young artists who’ve been captivated by new media in recent times. Javed Akhtar is surely an example. His works in Svikriti, as part of Birla Academy’s show of annual awardees, return to the tradition of oil that deceives a flat surface with cunning ploys.

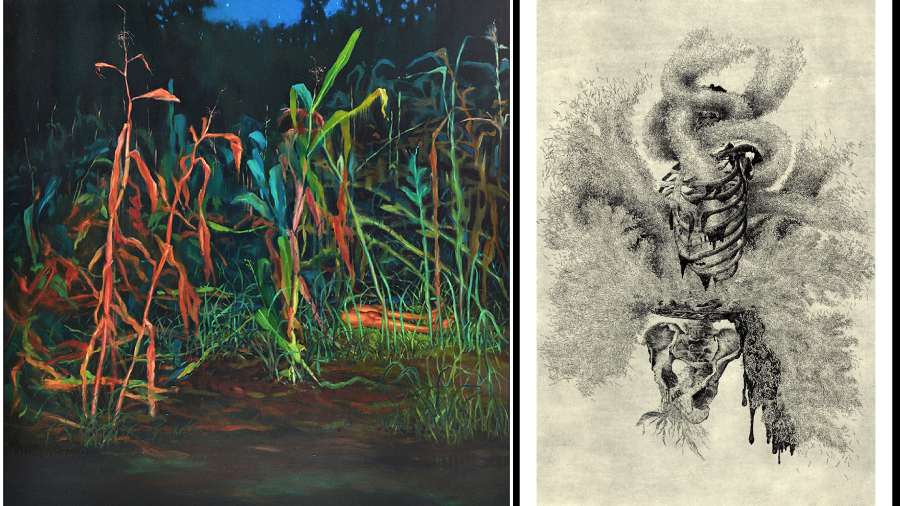

A sinister air stalks deep forests wrapped in night. Where tall, gangly, withered reeds lay siege to, and threateningly close in on, a pair of bare, inert legs in the grass (Fallen Angel, picture, left). Where a dug-up hole may be meant for victims of furtive figures lying in wait (Garden of Love). Where an insidious menace lurks in the dense green, while Lovers in the Forest are lost in passion. Since the bodies of The Wounded Lovers are split into ribs, could death be the companion of desire in this rapacious Eden with carcasses hung up like in butcher shops (Untitled lll)? The oil that stands out is cinematic in its composition and chiaroscuro. A silent procession through a forest bids a Last Farewell to an unseen comrade. This brings out the solemnity and secrecy of an occasion that affirms an unspoken solidarity among the participants. Akhtar also ventures into abstraction. But if probing the apparent can nudge unsettling intimations, why get trapped in Pollockesque exercises?

Another artist who upends pleasing visuals with dark hints is Gavara Satyanarayana. His miniaturist’s eye picks out details in organic and manmade forms to compose visual haikus in some of his woodcuts. But Memories I, II, IV — with their foodgrains and husks, banana leaves and suspended earthen vessels — are deeply nostalgic and also evoke the hunger of the deprived. The hints get darker in the finely-detailed etchings, particularly in Self-Realisation III (picture, right): much of life, the artist seems to assert, is about going Beyond Beauty to accept even the repulsive because that’s the reality.

Anirban Saha relives painful pandemic memories as a bewildering theatre of the absurd in his hand-crafted books, assemblages and an accordion-fold montage of sketches. His snide take on a Bollywood boast—“mere pas maaask hai” — turns serious when the artist asks “bureaucrats and ministers (to)...look at the people downstairs” and gets grim in his sketch of trussed-up corpses that carry “a reckless virus” which denies them the “address of a temporary morgue”. In his graphic novel, Safar, a haunting mix of despair and resigned stoicism among strap-hanging commuters is sensitively portrayed while some regular vendors aren’t seen anymore.

If Subhankar Halder chooses a strident allegory in quoting Goya to show how A Father Prepares to Sacrifice his Son, is it perhaps to diagnose India’s political system as an ogre devouring its own citizens? The small miniature next to the larger image recalls the Old Testament story of Abraham’s unquestioning obedience to God’s command to sacrifice Isaac, a symbol of overbearing authority. Elsewhere, multiple references to the power of a single finger — that can change governments through the EVM button — mark Halder as a political satirist. Although his use of Nepali paper is interesting, it could do with some refinement.

Perhaps his close encounter with death during the pandemic made Shantinath Patra keenly aware of the Perished Body. The 12 back-lit, mixed-media, photo-based panels are like x-ray imaging of body parts — some maggot-infested — scattered with clinical detachment. The technique, though not new, offers possibilities to explore if he can discover new ways of doing that. Anupam Chowdhury’s stoneware was a lively collection in which Batabriksha stood out for its political innuendoes.