For just short of a year, Anita Dube, who is the first woman to curate the ongoing Kochi-Muziris Biennale, researched, travelled and engaged in discussions with artists, her team and friends before she finalised the list of participants, which, to quote her, is a “fantastic mix of artists whose works I have admired for a long time, and completely new, eye-opening practices I was introduced to for the first time.” Besides, she goes on, “I wanted to de-centre the West as a dominant art producer, and that included visiting artists and conducting research of art practices through the Global South... there are a number of artists from Africa in this edition... (who have) just more of a platform than previous editions.”

Little wonder Thomas Girst, head of the BMW group cultural engagement, commented at a discussion the day after the biennale opened last December, that “...Kochi-Muziris Biennale is the greatest proof how much art matters...” BMW has partnered this international art event, on till March 29, from the very beginning. Exploring the Biennale, with 94 artist projects in 10 venues spread across 6,00,000 sqft, is a rewarding experience because of its surprise element. Here are five outstanding participants.

CYRUS KABIRU: His father was willing to bankroll his training in an art college after he finished school, but Kabiru had a mind of his own and he refused to follow a teacher because “I have my own art. I have my own way.” Art was his way of rebelling against the conventions of African life. As a seven-year-old in Nairobi, where he still practices, this 32-year-old painter and sculptor loved wearing glasses, and his father challenged him to make a pair for himself.

That is the advent of Kabiru’s fantastical, idiosyncratic and hellzapoppin’ C-Stunners, which are bifocals he creates by recycling junk he collects from the streets of Nairobi. He was attracted to junk because of the pile-up in front of his home. He thinks refuse is beautiful, and he fashions his sculpture with it. Colourful, eye-catching blow-ups of Kabiru modelling these futuristic spectacles, whose aesthetics are halfway between wearable art and performance, hang in two exhibition spaces. Kabiru has been making waves because his intricately-crafted C-Stunners touch on Afrofuturism, which is in the news following the phenomenal success of the film Black Panther, and obliquely refer to the politics of the African diaspora.

Cyrus Kabiru and his crazy bifocals Image: Cyrus Kabiru — SMAC Gallery

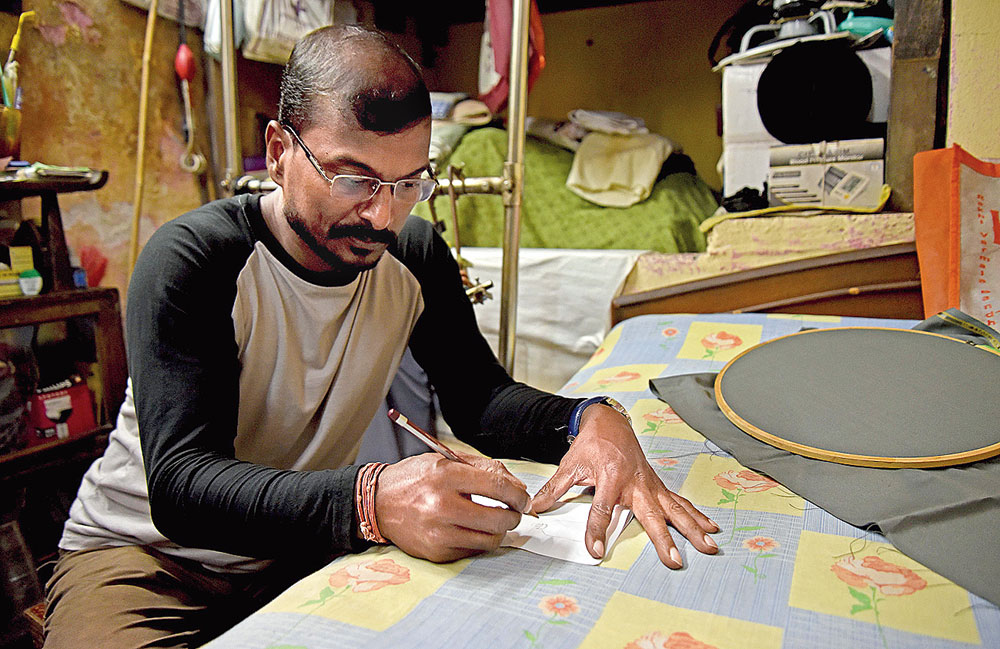

Calcutta autorickshaw driver Bapi Das turns his experiences into embroidery Image: Ankit Datta

BAPI DAS: This 39-year-old autorickshaw driver from Narkeldanga in Calcutta is an overnight sensation. The only participant to be chosen from Bengal, Das shares a tiny room with his mother, and chose the feminine craft of embroidery as his medium of expression. Anita Dube has said: “It is amazing what an excellent formal understanding Bapi has. Yet, he is untrained. I am looking at people on the margins.” Das’s vision is shaped by his experiences as an autorickshaw driver, and through his microscopic stitches he articulates his loneliness as he drives through desolate roads with street lights shining on the surface. The images he creates with the soft threads of a dupatta are not photo-realist but have a three-dimensional effect as they stand out against a dark background. The eight amazing images he created for the biennale titled “The Missing Route” are windows on this harsh reality of urban life, and these have attracted the attention of many visitors, including the Kerala chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan. Das created a contraption with wood and a magnifying glass to do his self-taught embroidery. But fame has not translated into money. Das’s tiny room is his studio, and he is struggling to survive.

SRINAGAR BIENNALE: Veer Munshi, the brains behind this project, had fled Kashmir in 1990 during the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits like himself because of the political upheaval in their homeland that left them destitute. Through this project, Munshi wanted to share the pain of both those who were born in conflict and continued to live there, or were affected and fled away, for “pain has no colour”.

Fourteen artists belonging to the Kashmiri Pandit community and the Muslim community came together to voice their pain. Among them are three to four photojournalists like Sanna Irshad Mattu, who made a video of a gravedigger, and Saukat Nanda, who documented women waiting for their children and husbands.

Earlier, there was always a middle space in spite of polarisation. But now that space is beleaguered, Munshi wanted to bridge this gap. Hence the installation of the Sufi darga, which is “the most marginalised space”. This is where both communities used to come and pray. That was Kashmiriyat, and Munshi wanted to invoke that lost culture. Inside are small coffins meant for children. The bones of children made of ravishingly beautiful papier mache are kept inside the coffins, bringing in the local craftsmen. “It takes you directly to the place,” says Munshi.

PANGROK SULAP: This collective formed in 2010 in hilly Sabah island of Malaysia produces giant woodcuts reflecting the social realities and problems of the farming community, usually, to the accompaniment of music. The first component of the name of this collective stands for punk rock — that is the way locals pronounce it.

The second half means farmer’s hut. Zayrul Rizo Leong, who is a co-founder of the collective in which “everybody is a leader” and was among the group of eight — all self-taught artists, achieving perfection through practise — that visited Kochi, says the artists double as musicians who play Sabah folk songs. They hold workshops for village folk to teach them the art of woodcut as a means of empowerment.

As the band plays the guitar, harmonica and the djembe (drum) people are invited to dance on the wooden plank on which the image is carved to take a print with offset ink on blackout cotton. The Malaysian group collaborated with artists in Kerala and produced woodcuts that incorporated motifs of the state. Here they played Kerala folk songs. They are happy that visitors danced to their music.

The archetypal images created by Juul Kraijer thereby allude to various psychological states and classical mythology, but are fascinating and mysterious on their own Image credit: Juul Kraijer

JUUL KRAIJER: This artist from the Netherlands creates images that, to quote the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, are a “sight to dream of, not to tell”. They are compellingly beautiful, and the viewer’s eyes are automatically lured to them, but at the same moment, the gaze is hastily withdrawn as the viewer feels a frisson of fear. “In French this state is wonderfully called Meduse”, says Kraijer, who has lived in Kerala.

Both in her drawings and her photographic images mostly in black, a spectrum of greys and white, she pairs her model with classical features that transcend time with serpents and other natural creatures that are beautiful but are regarded with awe and horror. The archetypal images created thereby allude to various psychological states and classical mythology, but are fascinating and mysterious on their own. “The magic of photography for me lies in being able to extract a lasting image from an ephemeral and near-to-impossible situation I have painstakingly set up in my studio,” comments Kraijer. In her drawings with charcoal, she gives free rein to her imagination. So her images are on the cusp between illusion and reality.

In her drawings with charcoal, she gives free rein to her imagination. So her images are on the cusp between illusion and reality. Image credit: Juul Kraijer

As the band plays the guitar, harmonica and the djembe (drum) people are invited to dance on the wooden plank on which the image is carved to take a print with offset ink on blackout cotton Image credit: Pangrok Sulap