Feeling alone

The army's up the road

Salvation a la mode and a cup of tea

Aqualung, my friend

Don't you start away uneasy

You poor old sod

You see, it's only me

Me-ee-eeh, o-o-o-oh

This is when Martin Barre’s Les Paul comes in, unhurried, laying out the contours of the journey he’s about to take on the fretboard, embedding a riff in the hearts and minds of generations of Tull fans. He eases in, naturally free flowing. Soon, he ratchets up the pace emphatically, and dives into the whirligig of emotion, screeching, bending and stomping. It’s the section of the song where all the dramatis personae appear to come together, standing face-to-face. It’s 50 years of Aqualung, the album named after the song. Do you still remember December's foggy freeze?

Thanks to the marvels of technology and the uncertainties of a pandemic, the world got to watch Jethro Tull founder-frontman Ian Anderson live-stream his thoughts on the genesis of each song in the seminal album of the iconic rock band that can still bring together folks across time zones to commemorate the occasion. From USA, Turkey, Poland, Serbia, South Korea, not to mention Calcutta, Mumbai, Bengaluru, fans had gathered Friday night, eyes preened on their devices to hear the 74-year-old tongue-flutist look back fondly.

Ian was only 24 when Aqualung was released. Not that he makes a big deal of it anyway. After all, the number of personnel changes notwithstanding, Jethro Tull has to its credit today 21 studio and seven live albums, setting aside a handful of compilations. The Aqualung album, he notes, marks a departure from the straight-ahead rock album styles and heavy guitars to arrive at a “dynamic mix of big riffs and aggressive music” punctuated by “singer-songwriter acoustic pieces”.

Ian says it was about his gaining the confidence to do songs that were in a more intimate setting. “As an album, it was social documentary, social realism, and touches on subjects, the everyday street scenario, people in a landscape,’’ he says of the 11 songs. The dynamism comes from the songs as well as their sequence. Once upon a time listening to an album from beginning to end was the only way to enjoy music seriously. Bookended by the weighty rock pieces _ the seductive power of the title track, the foot-stomping character of Cross-Eyed Mary and the frenetic urgency of Locomotive Breath _ are the soft “non sequiturs”. These are intimate acoustic delicacies about a son taking a train trip to pay a visit to his ailing father, soaking in the sun at London’s Hampstead Heath _ a la the Calcutta Maidan _ imagining a love so pure that it needs shielding by a string quartet and then winding up with an ode to school days where learning comes amid a deep understanding of power, its consequences and the responsibility that comes with it.

Pay attention to the lyrics and sense the extent of Ian’s heavy-duty introspection. Poverty and homelessness are a concern (Aqualung), stitched together as he says via a painting. Organised religion comes in for some deep scrutiny (My God, Hymn 43) with Ian making no bones about his feelings towards those who use religion as an instrument of power and control. Controversy? Oh yes, a few copies of the album were burnt in the USA, but that’s about all. “I got away with it. Nobody got hurt as far as I know.”

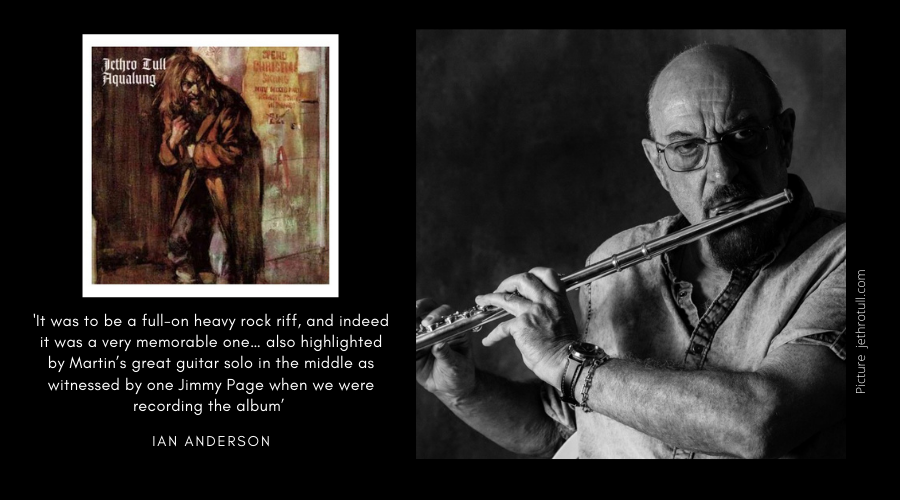

Listen in. Ian’s quite the raconteur. He has stories about a certain Jimmy Page’s presence at the recording of the title track’s lead riff and a novice bass player who went on to nail it

Aqualung

“The music, as I recall, probably came after the lyrics, but soon after. I remember writing the opening riff (hums the tune) as a loud electric guitar piece. But of course, I was at that time in a hotel room in the mid-west of America and I phoned Martin Barre in his room and said, ‘come over, I’ve got this new song… maybe we can just work on it together’. So, he came along with his electric guitar _ no amplifier, just a feeble tin tin tin, almost inaudible. I played him the riff and the chords on the acoustic guitar and said, ‘this is your part.’

It was to be a full-on heavy rock riff, and indeed it was a very memorable one… also highlighted by Martin’s great guitar solo in the middle as witnessed by one Jimmy Page when we were recording the album in Island Records’ Basing Street Studios. And Jimmy popped into our studio and watched that bit of the proceedings when Martin did his guitar solo live in the studio knowing that Jimmy was watching him. Pretty scary stuff. We didn’t return the favour ‘cause we were far too shy to go and intrude on the (Led) Zeppelin recording sessions.”

Cross-Eyed Mary

“It’s a weird one. But again, it’s about people in a landscape. And this particular one was an imaginary woman, probably flawed in some people’s eyes by being cross eyed, but none the less, I suppose, attractive in some way to men who wanted to pay for her favours. And it draws together a lot of stereotypes. It’s probably not really a politically correct kind of song _ and there are quite a few of those on the Aqualung album now that I think of it (laughs). If I was to write those today, I might just moderate some of the descriptive nature, titles, names just to soften it a little bit.”

Cheap Day Return

“This was a song written about a brief visit up to Blackpool where my father was quite seriously ill and in hospital at the time. Not knowing whether he was going to make it, I jumped on a train and went up to visit him from London. We only spent, I guess, half an hour together in a ward in a hospital and (it) seemed like he was going to pull through and was being well looked after. But I had to change trains, in fact, in Preston town in the north of England, where I stood on one platform and went to another platform and stood there in bitter cold stamping my feet to try and keep warm. Hence on ‘Preston platform do you soft shoe shuffle dance’. It’s a little ode to my father and perhaps more importantly to the nurses looking after him in hospital. He did come home and did live a few more years after that. So, it was a nice, memorable and a very short little song.”

Mother Goose

“Playing live on stage, I do Cheap Day Return and Mother Goose back-to-back as a little pair of allied songs. Different subjects (though) Mother Goose was really predicated on some of those summer walks around Hampstead Heath, a public park around north of London where in the summer you’d find all kinds of people from the dying days of the hippie times through to those just out exercising, having a good time. People would kind of dress up and be endowed with the blessings of the summer sun. I remember it as being a pageantry of colour, people were wearing lots of colourful clothes. It is indeed a kind of slightly surreal but interesting pastiche of topics. People probably scratched their heads listening to it, thinking, who is Johnny Scarecrow? Why is he doing his rounds? For the life of me I can’t remember.”

Won’dring Aloud

“One of those rare occasions when I write something approximating to being a love song. And I’m not very good at that sort of stuff. I am not really a heart-on-sleeve kind of guy. … Wond’ring Aloud, it’s a personal, imagined kind of a song. I guess it’s a waking up in the morning kind of a song... It’s rather poignant… I think I did two takes of the song, no edits or anything. But it was just an acoustic guitar and a voice. So, it had a little bit added to it in the way of some piano from John Evans, bass from our novice bass player Jeffery Hammond. And then I thought that it would be rather nice to hear a string quartet. So, I contacted an old chum David Palmer who’d worked with Jethro Tull even as early as 1968. And he’d done a great string quartet piece on a song back in 1968 called, A Christmas Song. And in a way we reprised that idea a bit. Being a relatively solitary acoustic piece but with the warmth of a string quartet which makes it one of those early songs where, I think, we did a good job of bringing together the elements of a classical string quartet with folky pop music.”

Up To Me

“Here’s another of those walking down the street kind of a song as I am seeing things and imagining people. Not so much imagining people. Seeing real people but imagining what their back story is. Who are they? Where did they come from? What do they do?”

My God

“The opening track of Side Two, My God, may well have been the first song that was written for the Aqualung album. It was performed live on stage some months before we actually got to record Aqualung. But I remember doing My God in the summer of the year before in 1970 at least in America. And it had slightly changed lyrics, but it was always a dramatic piece and a bit of a critique of organised religion. It’s not that I have anything against organised religion, but I think you’ve got to question the validity of people who use religion for self-aggrandisement, to make themselves look powerful or important and exercise some control over their flock.

“So, all of those things infused that song and the lyrics, and the drama of the opening acoustic pieces with piano and acoustic guitar through to the crashing in of the big riff that’s very much part of what Aqualung as an album is about. It’s about dynamics of extremes, musically. Again, lyrically speaking I might just modify two or three words in the whole text today in order not to be misunderstood as I was for that song back in 1971 when they burnt copies of Aqualung in the southern states of the United States because they thought it was sacrilegious and a huge offence. But I got away with it. Nobody got hurt as far as I know. Certainly, I escaped intact. So far!”

Hymn 43

“In keeping with one or two other things on Side 2 of the Aqualung album, it has obvious references to Jesus. Jesus of Nazareth, or in this case Jesus Christ, being perhaps held up to be something that may be he might have been a little uncomfortable with. We can never know. I am trying to be sympathetic and understanding of the huge weight placed upon the historic shoulders of Jesus. Tough gig. Almost as bad as being the Pope, really.”

Slipstream

“I love the little, short things. The little non sequiturs of music where you just have this tiny thing that lasts 20 or 30 seconds. There is no before, there is no after; just a tiny little glimpse of here and now encapsulated into this very narrow time-frame. So, it has a rather enigmatic but none the less nice little lyric that (after a long pause) does have an optimism about it, I think. But also, a rather gloomy side too. It is enigmatic. I’d like to think I am quite good at being enigmatic. It comes quite easily to me.”

Locomotive Breath

“Always an unpopular thing to talk about because people get their knickers very readily in a twist if you talk about population issues. But growing up in the ’70s it seemed quite obvious that we were on a real level of growth in terms of global population… We were entering into a world that was just colossal in terms of industry, commerce, greed, banking and investments and all of the trappings that come with a lot of people, a lot of mouths to feed, a lot of people to buy products. So, I wrote the song very carefully, I think, to talk about that runaway train of population growth. I was born in 1947. And in my lifetime so far, the population of our little fragile planet has increased to be slightly more than three times as many people living here as there were when I was born _ in one man’s lifetime more than tripling the population of our planet. So, we have a big job in trying to create levels of equality to feed those people to cope with a real jungle of folks.”

Wind-Up

“The last song on the album, which, I think, intentionally was called Wind-Up as a final song for the album, is one that begins with the lyric, ‘When I was young, and they packed me off to school and taught me how not to play the game’. Again, I am going back to my childhood days of being, I suppose, subject to the authoritarian regime of a grammar school that pretended to be a public school _ the English term of being a private school that was very old fashioned and traditional. Boys were caned. It was ridiculous. All of that is my growing up, part of my sideways glance towards education, my sideways glance towards religious education.

“But in many other ways I wouldn’t have wanted to miss that because it’s given me a sense, not only of a degree of anger, a degree of rebelliousness, but also a degree of understanding as to how people will use the degree of authority given to them whether they are senior prefects at a school or whether they are teachers. … and may be I’d have written the song a little bit differently with the wisdom of my years than I did back in 1971.”

The Aqualung livestream experience was heart-warming and rewarding for all. It’s fascinating how the same songs are appreciated differently over time. Back in 1994, when I was fortunate enough to meet Ian Anderson and Martin Barre in then Bombay when Jethro Tull was touring India, he had spoken of some songs that simply had to be a part of their live shows no matter where they played. “Realistically, the over 200 songs that we have recorded, only 25 per cent are useful live performance songs. Locomotive Breath is okay. Living in the Past is one that’s due for a little light retirement for a year or so. Aqualung has paled, but somehow it’s a song that a Jethro Tull concert would be incomplete without,” he said.

Aqualung the album, Ian agrees now fifty years from its release, is one of the most important albums for him and Martin Barre for sure. For him because it helped cement in him the idea of pursuing a varied repertoire of songs, both acoustic and heavy rock-infused electric. And for Martin because he was “really beginning to find his feet at that time as a soloist and having that ability to convey the drama of the Les Paul guitar which is what he played back then”.

As for Jeffery Hammond, he had joined the band three weeks before recording and had no experience of playing the bass guitar. Hence, he had to be taught song by song. “But to our amazement, once he’d got all that in his head, he became probably the most dynamic, expressive and entertaining bass player that we’ve ever had,” recalls Ian. “Entertaining because he was a great stage character.,. also because he did play all the right notes all of the time. He hardly ever made a mistake.”

Aqualung was remixed at the time of its 40th anniversary re-release in 2011 by British producer Steven Wilson who acknowledged it was a masterpiece but rued its poor sonic credentials. “What we did with Aqualung was really make that record gleam in a way it never gleamed before. I think a lot of people, including myself, have come around to thinking that the album is a lot better than they even gave it credit for previously. So, there is certainly something very gratifying about being able to polish what was already a diamond and making it shine in a way it never has before," he said in an interview to music magazine Innerviews.

Jethro Tull songs keep coming. They always do. Cut to 1972, a year after Aqualung, Thick As A Brick is released.

Spin me back down the years and the days of my youth.

Draw the lace and black curtains and shut out the whole truth.

Spin me down the long ages: let them sing the song.

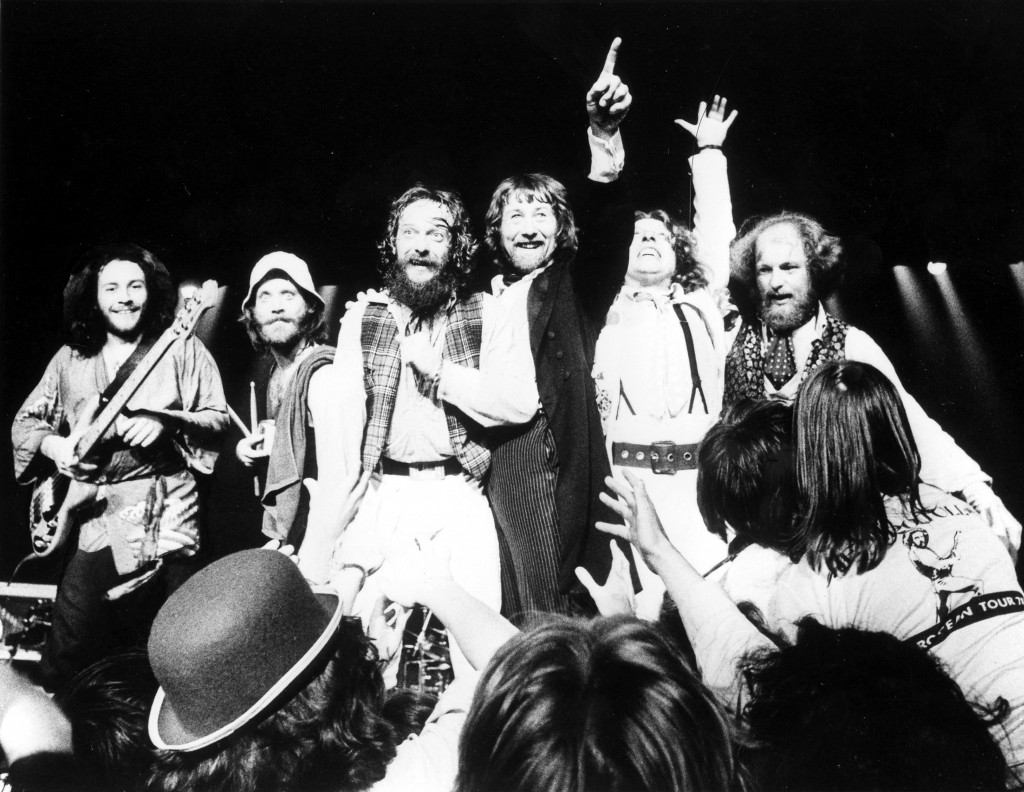

Jethro Tull circa 1977 (jethrotull.com)