A bedraggled figure, brutally kicked out of a Ram temple by glued-to-mobile phone Ram bhakts, starts chanting the name of Ram in a frenzied manner. As his chanting picks up speed, at one piquantly ironic moment RamRamRamRam becomes MarMarMarMar.

With this, the mood is set for writer-director-actor Makarand Deshpande’s Hindi play, Ram, that turns many a popular notion on its head. Staged at the annual Prithvi Theatre Festival in Mumbai, the play, apart from satirising other issues, debunks religion as practised by rigid, unthinking bhakts who know very little about the prince of Ayodhya.

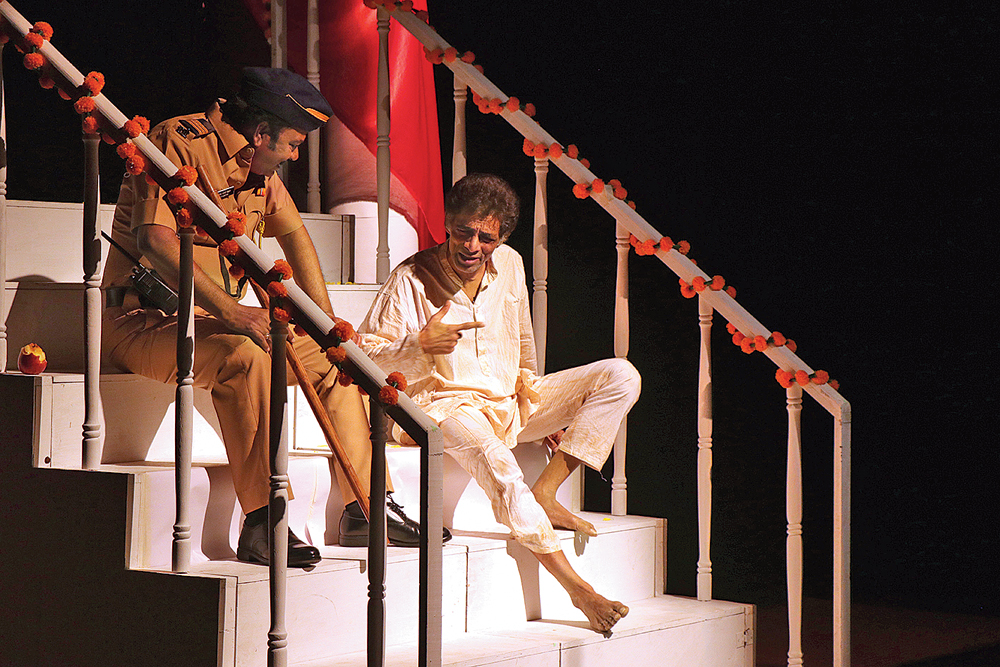

Enraged by the vagabond’s audacious muttering, the devotees phone the police to rid the scruffy “madman” from the vicinity of the temple. A constable arrives and the temple-goers go home, smug at having taught him a lesson. But the “madman” is far from being intimidated by the cop. Instead, he starts a chatty conversation with him about the Ramayana of which the cop knows only what he has gleaned from TV serials. Spoofing the serials and the Ram bhakts, the “madman” states, “Gyani hokar ghoomnewala agyani hota hai.”

He then sets forth to reveal the real Purshottam, contrasting him with those who exploit his name today. “Ram ne putra-dharm nibhaya. Vriksh ki chhaal aur mrig ki khaal odhkar vanvaas chale gaye. Unhe, Kaikayee ko diya, apne pita ka vardaan nibhana tha; na ki raj karna tha. Kartavya aur prem unka dharm tha… par aaj, shaasan aur adhikar ko Ram-dharm bataya ja raha hai. Kahin toh sandarbh badla hai, koi vichar mara hai, tabhi mujhe ulta Ram (Mar) sunaee de raha hai.” (Ram fulfilled his duty as a son by honouring the promise his father had given Kaikayee. Wearing the bark of a tree and deer skin, he retired to the forest instead of ruling over a kingdom. His dharma was duty and love. But today people are in power in the name of Ram-dharm. Something has changed somewhere. Some belief has died. That is why I am hearing Mar instead of Ram.)

Later, left alone, the “madman” decides to have some fun. He places a nondescript stone outside the temple and decorates it with haldi, kumkum and flowers. He is sure the stone will be blindly worshipped. It is. Mindlessly, devotees bow.

The constable is nonplussed. “Over there for decades they have not been able to build a mandir; and here it appears overnight!” he exclaims. Unwittingly, the simple cop has made a sharp comment on a burning issue.

As the play progresses, the constable starts envying the vagabond’s uninhibited ways. “For a little while I would like to be mad like you and break free of my uniform,” he confides. “Out here, on the streets, I have a lot of power, but at the police station I am at the beck and call of my superiors. I want to tell them that I don’t want to run your errands. At political rallies, I have to stand in the heat for hours on end. I want to tell politicians that I don’t want to stand there endlessly. In my miserable, little home, I am totally dominated by my wife. She married me because of my uniform and now she fights with me because of this uniform.”

The madman gives him a simple solution: “The next time your senior tells you to fetch tea, fetch it but instead of giving it to him drink it up yourself. When you are doing duty at a politician’s rally, pack up and go home when your duty hours are over instead of standing there, endlessly. Don’t plan madness. Just become mad.” Intrigued, the constable asks, “What were you before you turned mad?”

“I was many things,” laughs the madman. “At one point I was a drop of water, then a tree but was chopped down when I was asleep. When I had income, I was Tax. When I had expenses, I was Savings. Now I am GST and everyone is in trouble. At one point I was Gandhiwaadi, now I am Savarkar. I am a kamal ka phool blooming in the muck of elections. When I entered politics, I forgot everything, insaan se haivaan yun ban gaya…” Head reeling, the cop replies, “To understand you one has to be mad!”

The Ram bhakts return. Irritated at seeing the madman, they pick up the stone they had prayed to earlier, to hit him. The constable tries to protect him but the devotees dare him, as a Hindu, to beat him. Mar mar mar, they urge. The constable complies while the devotees film the act on mobiles to upload on Facebook.

Suffused with satire, the play touches on wide-ranging topics. From religious humbug, environmental destruction, moral policing and women’s vulnerability to parochialism, writer Deshpande looks at various issues, threadbare; even taking a dig at former prime minister Narasimha Rao’s lack of humour. But, perhaps, Deshpande packs in too much. His spoofing of television serials depicting the Ramayana and the Mahabharata is long-drawn and over-the-top, making the play sag in parts.

However, the denouement restores the sharp tone with which the play begins. After they hang the vagabond, the Ram bhakts are shown climbing the stairs of the Ram temple, chanting Ram’s name in apparent devotion. So immersed are they in vacuous chanting that they don’t notice a splendid figure in blue walking down the stairs and out of the temple.

Oblivious to the fact that the Lord has walked amidst them and left the temple, the bhakts continue with their RamRamRamRam.