The exhibition, Birth of An Artist: The Early Years of Abanindranath Tagore, is now on view for an indefinite period of time in the cavernous Durbar Hall of the Victoria Memorial Hall. Although 59 works, including one stone self-portrait, are exhibited here, these scraps of friable paper are completely swallowed by the enormous dimensions of this hall, where large canvases by European artists like Thomas and William Daniell and Johann Zoffany were displayed not very long ago.

The Calcutta Gallery was dismantled and the Durbar Hall was deprived of all its artwork just before January 2021 to make way for the Nirbhik Subhash exhibition, which was inaugurated by the prime minister on January 23, 2021. VMH hasn’t recovered from the shock yet.

The early works of Abanindranath were acquired from Ujjal Bhandia in 1984, from P.C. Kejriwal in 1989 and from Syamasree Tagore in 2004 and 2006, according to the documentation unit of the VMH. The exhibition was curated by Debdutta Gupta.

This is an important collection that throws light on the nascent talent of Abanindranath, who was motivated by the swadeshi movement to change the course of modern Indian art. He shelved the predominant Western academism taught in art schools and introduced a closer study of the Indian artistic heritage. The collection certainly deserves a more in-depth study than a cursory glance to find out the possible dates on which each work was executed although clues may be scarce. Without a timeline, viewers feel a little clueless now.

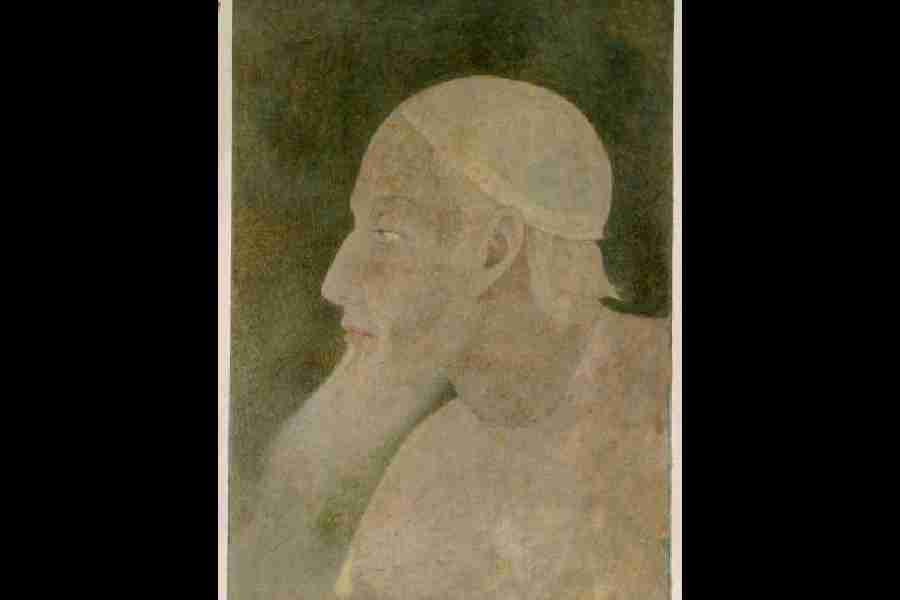

Abanindranath had taken lessons in art from the Italian artist, Olinto Ghilardi, and later the English painter, Charles L. Palmer. E.B. Havell, the principal of the Calcutta School of Art, persuaded him to study Mughal miniatures. There is a delicate watercolour head of Aurangzeb here (picture). What we witness in this exhibition is Abanindranath’s artistic journey, beginning with feeble attempts at drawing with a pencil and watercolour. The lines and brushstrokes firm up over time. The Western influence is quite apparent, even though he drew the landscapes, greenery, hutments and sections of mansions or bungalows he saw around him at Jorasanko and the Konnagar retreat where his family holidayed. There are some still lifes as well: a hookah, and a sofa with a woman floating above it — surrealism by accident. There are occasional glimpses of village life and the wide river with a buoy floating on it.

Gradually the figures — a woman with an infant in her arms and a flower-like maiden in a sari — were more confidently modelled. Abanindranath gave letters of the Bengali alphabet avian and piscine forms — Chitrakshar. There are some examples of these experiments. He essayed several portraits of the people he knew with pen and ink. Some of these were intensely observed. The visiting Japanese thinker, Okakura Kakuzo, had sent the artists, Hishida and Taikan (Abanindranath did his figure study), and they introduced Gaganendranath and his younger brother to Japanese techniques. Then the delicate bamboo leaves sprouted on paper.

Interestingly, there is an impressionistic sketch of a performance of Rabindranath’s Natir Puja at Jorasanko. Abanindranath was a master of the art of caricature. He loved poking fun at himself. Here, he is a crusty old man chewing on a cheroot but with a soft spot for his grand daughter. These are quite as delightful as his Edward Learesque designs for children’s costumes.