Landscapes have come a long way since the Greeks and the Romans painted them on walls, or even since they were first formalised as an artistic genre in 4th-century China. In India, where landscapes had traditionally only formed a backdrop in narrative-driven, figural paintings, landscape art arrived with the travelling European artists who brought the aesthetic of painting mountains, rivers and trees against the sky and a distant horizon, transforming nature as a subject in itself. CIMA Gallery traces the evolution and the varied facets of this genre in India in its ongoing exhibition, Landscape: Summer Show 2023 (it is on view at the gallery till July 15).

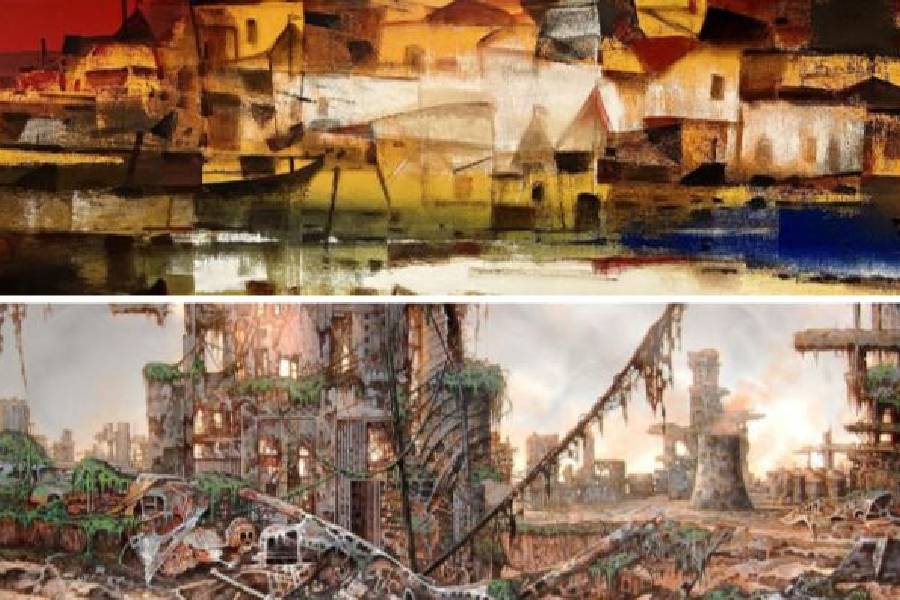

The entrance walls of the gallery establish its expansive vision that includes the traditional, the non-traditional and the experimental. The predominant work that draws the eye is The Riverside by Paresh Maity (picture, left), an arresting painting of Varanasi’s signature ghats. To the left is Prashant Patil’s shadow map created from the reflection of glue-gun outlines on net, and to the right is a Mewar miniature of a hunting scene. Freed from formal structures, the show overwhelms viewers with various styles and ideas. Rabindranath Tagore’s stormy watercolour, Abanindranath’s portrayal of rural repose, Jamini Roy’s verdant gouache on board, Ramkinkar Baij’s busy sketch, Gopal Ghosh’s tranquil shades — each work evokes a sense of peace and solitude that is traditionally associated with landscapes.

There is more.

Ganesh Haloi sets aside abstraction to paint a quaint thicket; Lalu Prasad Shaw’s exquisite pastel work conjures up a village scene; Jogen Chowdhury’s sharpness of lines gives way to a skyline with thick smears of ink on paper; Paramjit Singh’s impressionism soothes, as does Ramananda Bandyopadhyay’s layered landscape.

Attention to detail can change a landscape from being just art to being a social register. This is evident as much in the works of masters like Haren Das as in Departure by Sudhakar Chippa, whose intricately textured tale of migration is as poignant as it is sharply critical of urban life. Bhagyanath C. is keenly observant of the many planes on which life unfolds even within the same landscape, while Shreyasi Chatterjee’s scene has hundreds of little tales embroidered in every corner. Vinod Ambalathara’s stunning Kasaragod Landscape hides details in plain sight behind the shimmering Western Ghat-topography; Buku Sarkar does the same behind the veil of brown smog enveloping her Dawn Series. Srihari Datta and Rajendra Dhawan, on the other hand, opt for abstraction; their works are reminiscent of familiar landscapes, but seen through a hazy lens; they are difficult to pin down.

The other artists are more explicit in expressing their concerns. Amit Singh Slathia’s Gleaners in the Zone of Conflict, where women gather empty shells and landmines from verdant fields while vultures loom above them, is an example. Bahuleyan C.B.’s Camouflage (picture, right) is even more direct with its post-apocalyptic scene, which bears an uncanny resemblance to photographs emerging from Ukraine at the moment. Arko Datta’s video montage captures the sights and sounds of Sunderbans’ landscape disrupted by a storm and how life goes on in spite of it.