From theory to praxis and back again for modifications is the circuit of those who shift gears: from interpreting the world to changing it. Well, it isn’t this Marxist prescription that inspired the show that ended on June 30 at Experimenter (Ballygunge Place). Drawn from Practice II was more about the “foundational role of drawing” in art. But Sanchayan Ghosh’s spectacular installation recalled how symbiotically entwined word and work, verbalism and activism, are as he quoted from Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

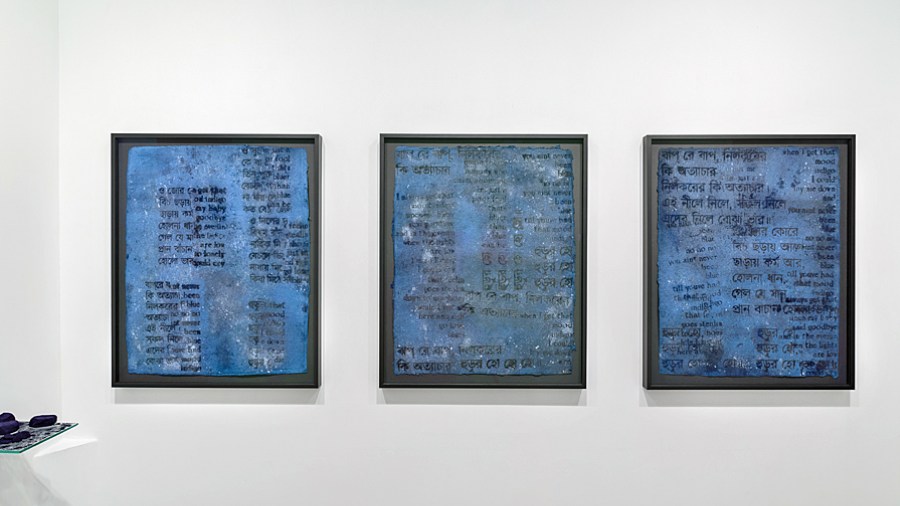

The discovery at the show for art-watchers, though, was Bhasha Chakrabarti. Paper made from blue jeans, indigo and other things into aged parchment was replete with references. Its text, on the debt trap the indigo planters led peasants into, was recited by a plaintive voice like a blues ballad. That, along with displayed pieces of blue denim, took Blue Notes (picture) from the Indigo Revolt of Bengal’s ‘free’ ryots to the angst of ‘freed’ African-American slaves, both events from the mid-19th century. Just that one word, blue, opened up verbal connotations and parallel narratives of torture in two theatres that were separated by half a world but converged through persecution at the bottom and profits at the top.

A plaintive tone informed Seher Shah’s Notes From a City Unknown. Against a ground of dense black were interludes of little white shapes, flecked with grey. The prints looked like diagrams of stage blocking. The little notes that accompanied them had the compressed, staccato litheness of haikus in describing the artist’s city, Karachi, that’s both “distant and familiar” to her. When she writes, “In the corners and edges of the city/ a wall of executions/ she rests her head on a pillow of iron”, you recognise the cameo as the universal signature of heartless cities and their homeless. Elsewhere, on three panels, the text was repeated, but with inordinate gaps between the lines, words and letters, turning it into strange, irregular, floating patterns of glyphs: the familiar made alien.

Patterns have been part of Ayesha Sultana’s sport with geometry. Coating paper with graphite is a strategy that intrigues viewers for the smooth, metallic glint of the surface. Sharp, precise creases in low relief, played on teasing permutations of lines and angles, were a riff on the suite, making it into a single theme with captivating variations. Prabhavathi Meppayil’s patterns were even more reticent, withdrawn into an inaudible, meditative hum as it were. Particularly in fifty three twenty two, with lines of minute motifs inscribed into gesso. There was a change of scale from little to large with Sreshta Rit Premnath’s sculpture of fluid curves, precariously balanced on limbs that seemed on the point of giving way.

As far as scale goes, large became monumental in Sanchayan Ghosh’s installation. But what was striking wasn’t so much the scale as the way the artist took Paul Klee’s enquiry into the swastika from The Thinking Eye to anchor his discourse on power and protest.

The large space was sliced by lean beams into what looked like Mondrian layouts erected into a skeletal structure. Wedged in the multiple perpendiculars made at the points where the beams met — including up above your head — were transparent (acrylic?) sheets with graphics and text. Walking into and around the installation, minding the protruding segments, not missing the graffiti on the walls, you encountered revealing data. Not just about the persistent legacy of the clockwise swastika but also about the undying spirit to fight back and prevail.