Amidst an overflow of do-it-yourself dance projects replete with fuzzy footage and some successful experiments, a few online festivals live-streamed on user-friendly platforms by experienced organizers engaged the attention. Spectacular new work, revamped excerpts from existing ones, along with a plethora of time-honoured pieces central to classical dance forms were put together in three recent festivals: Bhavaye Paramatmanam from the Aim for Seva Trust, Prana — The Life Force from Sanchita Dance Foundation and a music-and-dance programme put up by Shinjan Nrityalaya, each of which was spread over several days.

Together, they brought home a point or two about classical dance traditions and the dense complexities of metaphor and transfixing poetry that can be — and have been — fashioned out of it by individual creativity. However, it is interesting to note that very few of the works were executed in a way that they could exist exclusively on screen. Dance in the lockdown era, with the exception of some works made by a few choreographers, has clearly remained mainly proscenium-oriented, even if they were designed during the pandemic and some were cleverly tweaked to suit the digital format.

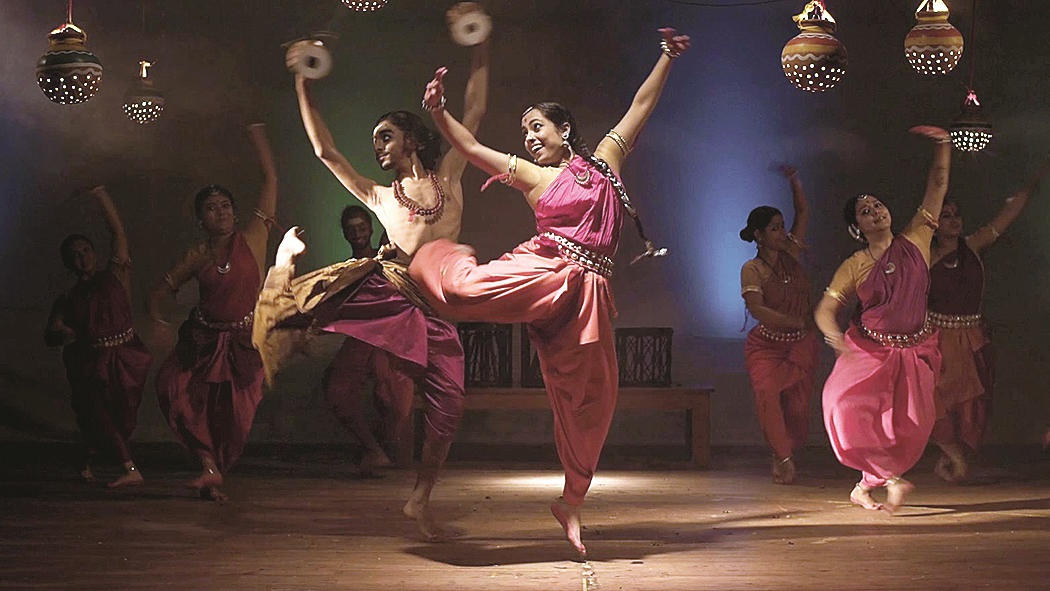

Bhavaye Paramatmanam featured, among other dance performances, Sharmila Biswas’s Shiv Shakti (picture). This was a piece that had had its genesis in a locked-down time of intense introspection, anxious coping and a driven search for newer expressions. The medium it adopted was powerfully cinematic in scope. Themed on the connection between the active energy of the animate world and the passive vastness of the great inanimate, it was a compelling work dazzlingly executed with Biswas’s visual imagination and grip over the idiom.

An extract from Debashree Bhattacharya’s ambitious choreographic work, Niravadhi, grappled with the abstraction of the sounds and silences of the soul through a fantastic contemporary energy she infused into traditional Kathak.

Sanchita Dance Foundation’s seven-day festival brought together an eclectic mix of dancers, from emerging to established exponents of the various classical dance forms. All the works remained within the scope of conventional expressions and household themes. This series included a gamut of classical dance forms. One of its high points was the delightful mother-daughter duets of Vyjayanthi and Prateeksha Kashi themed on Radha and Krishna and Sita and Bhumi. The Kuchipudi dancer duo infused life into the dance pieces with their extraordinary chemistry doing the talking for them. Aloka Kanungo’s Bilahari Pallavi and Champu had the stamp of her guru, Kelucharan Mahapatra. Darshana Jhaveri, a stalwart of the Manipuri form, delivered a fine demonstration of the traditional Manipuri piece on Radha. The love of Radha and Krishna was also the theme of Sanchita Bhattacharya’s offering, Chaitra Chandra, that made philosophical connections between the erotic and the spiritual.

Shinjan Nrityalaya’s programme combined discourse, demonstration, music and dance to present a well-rounded celebration of the performing arts and some principles governing them. A Sattriya Nritya solo by Sharodi Shaiki, Parul Shah’s work, Buddha, and Rajashree Shirke’s Kathak were part of the event that concluded with a vivacious collage of recitals by young Odissi dancers. The world of performances is poised at a moment in time when the frustrations of being homebound continue to plague the world and gatherings are still untenable. The novelty of the online platforms has been replaced by a deep digital ennui. More exciting spins to old material would be thrilling to watch.