The history of the feminine form is long, varied and complex in Indian art, ranging from semi-draped apsaras, yakshis and erotic temple architecture to the more conservative portraits that emerged with the influence of Persian-Islamic cultures and on to the more modernist Indian approach taken by the Bengal school. Feminine Facets, an online exhibition of small-format works organized by Emami Art, has a specific focus, exploring the portrayal of women by six eminent artists from Bengal: K.G. Subramanyan, Rabin Mondal, Jogen Chowdhury, Lalu Prasad Shaw, Ramananda Bandyopadhyay and Arunima Choudhury.

Women and their lives seem to have been the principal fount of Subramanyan’s creativity, accounting for more than 50 per cent of his drawings and sketches. He often depicts the dynamics of their changing relationship with a patriarchal environment. Women are depicted juggling – quite literally - children and amidst family; while being a part of a domestic whole, they are also complete in themselves. The opacity of gouache combines with broad and assured strokes to render to the canvases a two-dimensionality, veiling the expressions of Subramanyan’s women.

There is a marked Bengali essence about the women on this show. But Subramanyan’s works are not tinged with such regional markers; neither are the ones by Rabin Mondal. In the latter’s works, women’s faces are lined with diverse emotional creases: pain, sorrow, anger, anguish, loneliness, exploitation, but not defeat or hopelessness. Mondal’s deftness with ink and pastel gives an etching-like texture to his work that stands out even on a screen.

An artwork by Ramananda Bandyopadhyay Emami Art

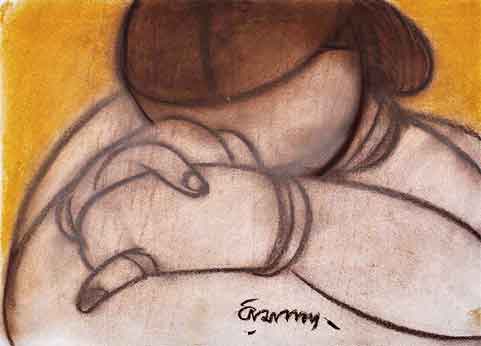

Ramananda Bandyopadhyay’s poetic lines and the hidden or averted gaze of the women he etches offers scope for imaginative interpretation. The body language of these women evokes a sense of power even though their forms are bent with the weight of everyday indignities (picture). His powerful drawings, enhanced by the touches of colour, combine the elegance of classical art with the simplicity and earthy innocence of Bengal’s folk art.

The two portraits by Lalu Prasad Shaw are dissimilar both in style and mood. There is the immaculately groomed woman — straight out of Shaw’s Babu-Bibi paintings — with a mirror in her hand (picture); seemingly all’s well with her world. Then there is the other, a gaunt face covered in shadows; is she the reflection of the woman gazing into the mirror that she holds?

Arunima Choudhury ’s women convey a sense of benign, inviting, wholesome femininity. Their identity is well-integrated; their sense of self at perfect ease with their social role. The narrative around them has a comforting serenity because these women embody a certain domestic beatitude, not anxiety or conflict that unfolds on the other canvases. Jogen Chowdhury outlines the female form: here the body speaks in silence. He places them against a vacant background, refusing to elaborate on place or environment. He interprets the human form as simplified, as if through x-ray vision: attenuated, fragmented, reconfigured and rephrased, thereby intensifying its visual and conceptual expression.

This exhibition is an invitation to explore how the artists imagined the woman, not so much as a model, but as a matrix to capture the wide range of aesthetic sensibilities that course through her body and society.