Any mention of Santiniketan evokes a sense of idyll in the Bengali mind. It is, after all, the beloved bard’s abode of peace. Images of red lateritic soil, a slow-flowing Kopai, sonajhuri and eucalyptus trees swaying in the wind flit through the mind’s eye. Then there are the verdant paintings of Santiniketan by Rabindranath, Gaganendranath, Nandalal Bose, Benode Behari Mukherjee, where, even in the lightest of black and grey watercolour washes, nature seems alive and thriving.

But the reality in the 21st century is very different. Ironically, people flocking to Santiniketan in droves in search of peace have eroded its tranquil landscape. Its signature red soil is now strewn with construction material as far as the eye can see. It is this stark and dispiriting landscape that Chandra Bhattacharjee portrayed on his canvas at the exhibition, Santiniketan, curated by Jyotirmoy Bhattacharya at The Harrington Street Arts Centre recently.

Bhattacharjee’s choice of medium, dry pastel and charcoal, would be perfect for depicting the texture of the red soil of Santiniketan. Instead, most of his canvases are in shades of black, refusing to let the viewer be lulled into a false sense of the bucolic. In the few canvases where shades like burnt sienna are employed, it is done to striking effect to act as a foil to scattered signs of ‘development’ like piles of stone chips and concrete bars in black and white. Elsewhere, trees and snapped branches remind the viewer of the aftermath of a storm, but this one was wrought by humans.

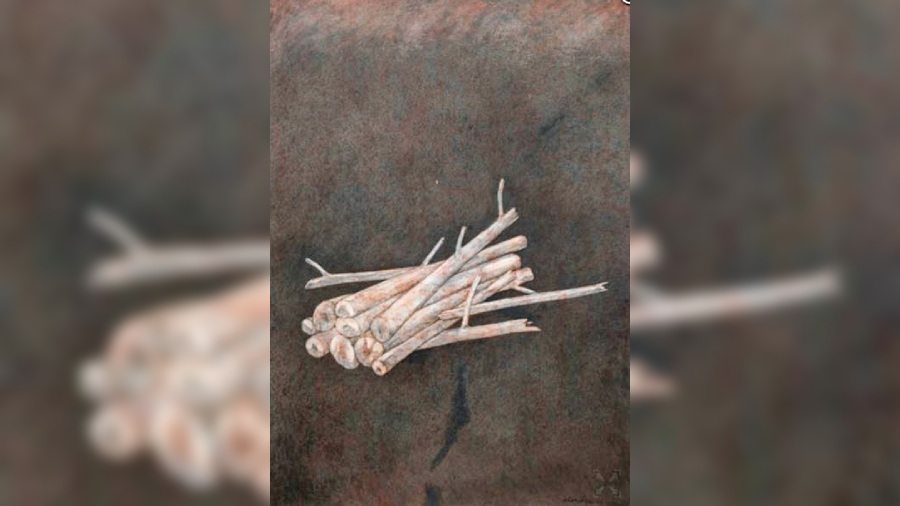

Occasionally, one can spot shapes that are reminiscent of the works of the Tagores — especially in the trees or the overgrown kaash — but these are black and white nightmares that recall the past to induce terror and not peace. What makes Bhattacharjee’s work most compelling is his sparse grammar — a large canvas of sooty darkness with nothing but a pile of whitish logs that bring to mind a pyre in the centre — which makes an impact that a more detailed scene could not have.

Bhattacharjee’s works seem almost symbolic and surreal, devoid of any human presence. But their power lies in the fact that the dystopian Santiniketan that Bhattacharjee sketches is frighteningly real.