The cataclysmic events related to the Partition in 1947 have scarred forever the lives of the people of the Indian subcontinent. Besides causing ripples periodically on both sides of the border, its seismic effects resulted in the upheaval that led to the bloody birth of Bangladesh in 1971. ReReeti Foundation, which works closely with museums, cultural organisations and heritage sites to meaningfully engage with their audience, launched an immersive and interactive exhibition titled Un.Divided Identities (October 15) aimed at capturing personal stories of the mass migration and carnage that followed Partition. The virtual exhibition is a choice-based, graphic-novel-style experience (complete with appropriate sound effects), using representative characters with stories of migration.

Viewers are invited to step into these real-life stories based on oral history interviews with Partition survivors in their community. These were conducted by school students across India, Pakistan and Bangladesh as well as youngsters from India and South Asians from Glasgow who were involved in all aspects of building this project, from research and web development to animation and illustrations. Although British Council is one of the many collaborators in the exhibition, the dark truths of the Empire are still not taught in schools in the United Kingdom. In 1997, the late Queen Elizabeth II did visit the site of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919, but stopped short of apologising for it. Reparations for the Partition victims — they ran into millions — have never been seriously considered, although the then UK government could certainly not wash its hands of it.

The roles played by the British divide-and-rule policy, Cyril John Radcliffe — reluctant though he was to rush it, he dismembered the subcontinent along religious lines — and our national leaders in bringing about the Partition should have been mentioned in a more pointed manner. Although it is targeted at young students, this is a rather bloodless account of one of the most calamitous incidents of recent times. Partition’s enormity is lost. Being in English, the exhibition will be accessible only to Anglophones, although most victims spoke their natal tongues.

Four flashpoints have been chosen as the theatres of tragic situations in which individuals are caught. They are Hyderabad (Sindh), now in Pakistan, in February 1948; Khulna (former East Bengal), now in Bangladesh, in November 1946; Firozpur (Punjab) in March 1947; and Jalandhar (Punjab) in September 1947. So it is a Sindhi Hindu factory manager who migrates to India from Hyderabad as the situation becomes increasingly frightening in Pakistan. In Khulna, a Hindu-Bengali zamindar family decides to move to Calcutta’s Queens Park. In Firozpur, a Hindu doctor risks his life to treat injured Muslims. Lastly, Muslim-majority Jalandhar is apportioned to India. So a Muslim landowning and farmer family of Jalandhar has no option but to pull off a great escape to Lahore.

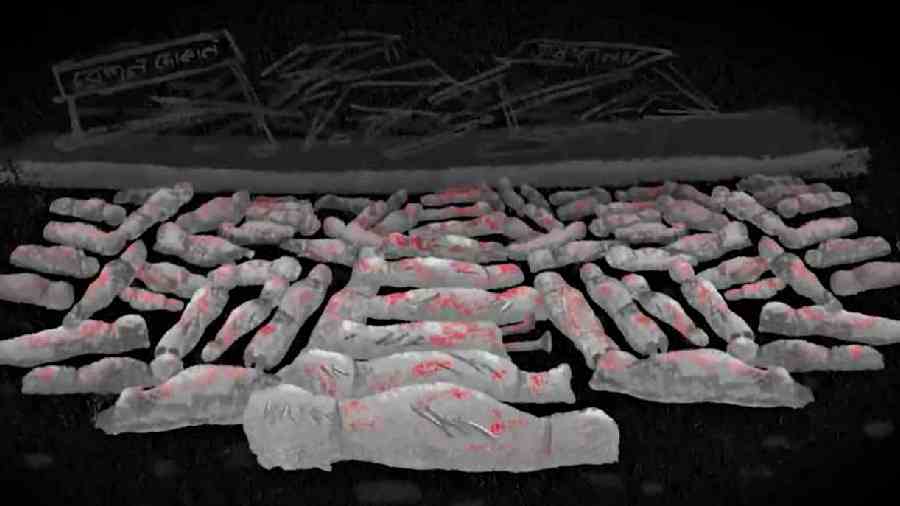

However, these are not just four linear narratives for viewers have the choice of making moral and practical decisions for the characters whose life and death may depend on these. For once, it is not just Bengal and Punjab and the focus shifts to Bangalore’s reception of refugees. Most of the visuals are in dramatic black and white, and colour, particularly red, is used judiciously. The Bengalis, however, are anachronistic — they sat on floors for meals then. Women, irrespective of age, wore sarees, draped differently and used a ‘boti’ to slice greens and fish.