Walking through the magnificent Indian Museum to see Delhi Art Gallery’s Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav show, March to Freedom, which ended in September, the first thought that came to mind was of a thirsty sponge soaking up every drop of wealth from Bengal, post Plassey and Buxar, to squeeze it dry at the East India Company’s headquarters in London. However, the few drops that dripped here were made good use of by enlightened scholars like William Jones, a benign by-product of European intrusion.

Tracking this India-Britain encounter by way of period prints, the first section of the show guided one through the march to Empire that preluded the march to freedom. On the fringes of political intrigue, battles and the unchecked fleecing of peasants, European historians, philologists and archaeologists were busy recovering for an amnesiac, diffident and divided people much of their own history and heritage. Whether it was Harappan antiquities and the linguistic kinship of Sanskrit with Greek and Latin or the decoding of the Kharoshti and Brahmi scripts and the reconstruction of the Ashokan period or the Ajanta caves, the revelations were startling.

Were it not for European artists and engravers, how would one know what different sites looked like two centuries ago? Like the breathtaking Northern Entrance of Gundecotta Pass (circa 1800) by Thomas Anburey or the Fortress of Gwalior (1804), spread across a stark, rocky table-top hill, seen from the perspective of Francis Swain Ward on the ground below, or Charles D’Oyly’s Garden Reach (1848), a colour litho with the subtle details of etching.

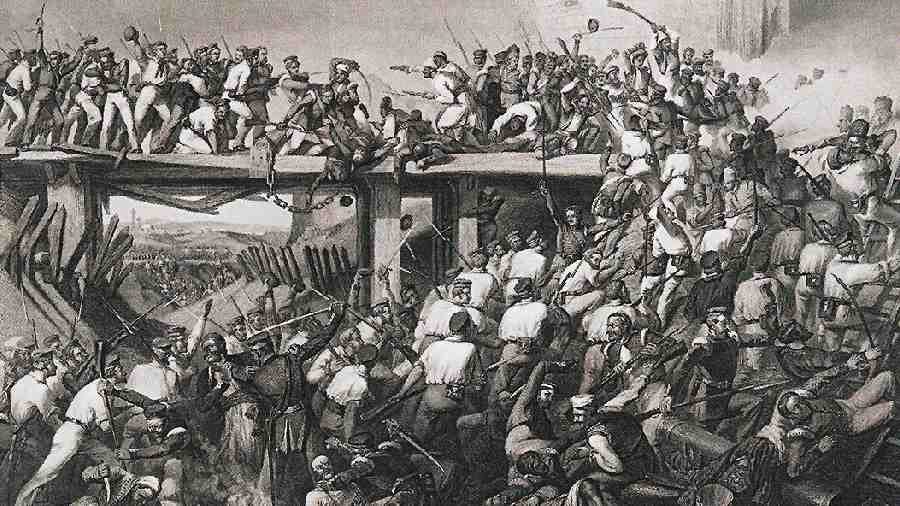

The re-creations of raging battles with numerous figures and painstaking minutiae are captivating for their technical finesse. The suicidal sense of honour in Tipu’s last stand, for example, comes across as a moving image in Henry Singleton’s print (circa 1802). The Battle of Chillienwallah (1849) is a dramatic representation by Henry Martens, but it’s M.S. Morgan’s Storming of Delhi (1859, picture) that’s charged with the fierce do-or-die desperation on both sides as surging foot soldiers clash in the final stages of the Revolt of 1857.

The Indian struggle for freedom that was once established as a linear story in largely city-centric colonial histories had ignored tribal uprisings for decades. But the collector’s item documented in the show mentions the Santhal and Kuki revolts. Reproduced in the volume is an unknown artist’s engraving (1856) of “600 Santhals” attacking “50 sepoys” during the Santhal hul — provoked by their mainstream Hindu tormentors, actually — that boosts the imperialist narrative of the white man’s burden premised on ‘native’ savagery. Incidentally, the revolt “wasn’t suppressed without bloodshed…” goes the prim understatement of a British source, “…indeed, half their numbers perished.”

Themes like trade and communications, tourism and the arts, politics and protest, portraits and events covered the broad, multi-coloured canvas of free India. Not only did the show give space to the obvious — like the works of well-known Indian artists from DAG’s handsome art and artefacts collection — but it also, with an insightful feel for the popular pulse, included the See India posters displayed inside trains: a beguiling journey through the land’s rich diversity.

Works by Atul Bose, Sudhir Khastagir, Radha Charan Bagchi, K.K. Hebbar, Chittaprasad, Haren Das, Sreenivasulu, K.G. Subramanyan, Prakash Karmakar and others certainly lent weight to the show. Equally important were the photographs, including those of Gandhi by the legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson and the stalwart, Nemai Ghosh. The frame to cite, in particular, is Ghosh’s still from Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj ke Khilari, based on Premchand’s story. What could evoke the contrast of cultures and eras more sharply than this image: two feudal lords consumed with an addiction like chess, while another kind of chess was being played by smarter players elsewhere?