Selfies and holograms just about flavoured the 2014 polls, while in 2019, digital media was used widely and aggressively in campaigning and voter mobilisation. And now we are at the door of India’s first AI-influenced general elections. At its most benign, AI or artificial intelligence is being used to research and script speeches.

“While each political party has designated people who script speeches, ChatGPT can do in 10 minutes what a team can achieve in six hours,” says Kalyaneshwar Sarkar, who owns Standard Publicity, a Calcutta-based adver- tising agency.

But it is not only about turnover time. A Bangalore-based tech expert who does not want to be identified says, “If a political party is trying to script a speech for the rural audience of a specific geography, ChatGPT will do a more thorough research. It will be able to find out the history of the place, the people living there, their heroes, local customs, rituals, religious beliefs, the local dialect and the issues that worry them the most.” Adds Nikhil Pahwa, who is a tech policy expert and founder of digital news portal Medianama, “When AI was not being used for electoral campaigns, candidates used to prepare a general speech that would apply to a wider audience. Now the messages are granular, more personalised because the Internet has penetrated the remotest corner of India.”

In Bengal, the concerned TMC and BJP spokespersons don’t admit to using AI. Priyanka Chatterjee, the social media convenor of South Calcutta BJP unit, says, “We are not using ChatGPT for such purposes. There is something called a plagiarism check.” But experts point out that for a fee, any user can purchase a filter and get past such policing.

The CPI(M) social media cell is more candid. Yes, they will be using ChatGPT for scripts and also translations.

Speaking of translations, the BJP is already using Bhashini — an AI-powered real-time translation tool — to reach out, most crucially, to the electorate south of the Vindhyas. And the Congress, reportedly, is planning to

use AI to “generate audio messages in Rahul Gandhi’s voice in multiple languages”. And the platform for all of these is social media.

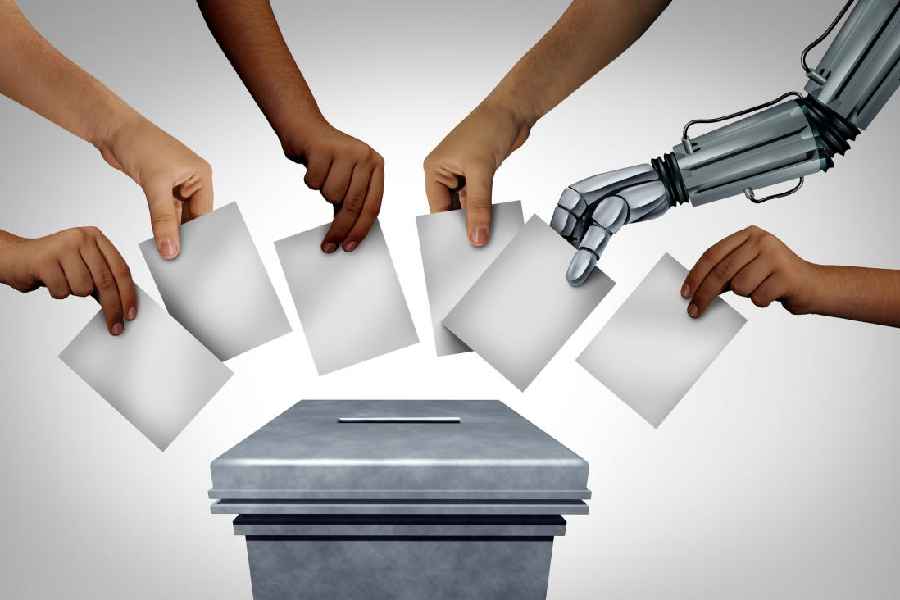

Before 2022, AI was predictive. Based on a user’s Internet footprints, it would predict what someone would buy, what ads they would like, what movies and perhaps even who they were likely to vote for. Some fear that AI has already been used to select candidates in some cases.

In its post-2022 avatar, AI is more of a generative tool. Soumyakanti Chakraborty, who is a professor of infor- mation systems at IIM, Calcutta, says, “There are two sets of voters. Voter A who has already decided who to vote for and Voter B who is yet to decide. Generative AI is targeted towards Voter B. AI will identify such voters by analysing their Facebook and Instagram posts, likes and comments, and then work on them.”

And to do so, experts fear, AI will amplify data, predict winners, slip in opinion polls on social media.

Bivas Chatterjee, special public prosecutor for cyber crime cases and an AI certified professional, says, “Big Data is going to be used for opinion polls. The flip side of this is that it may not provide the opinions of only Indian voters. Foreigners might have also expressed their views.” Big Data is the weighty name for all information available on the Internet, this includes people’s behaviour, reactions to socio- political issues and participation in political discussions.

And then, of course, there are all those AI-generated fake videos such as Karunanidhi praising son Stalin for his able leadership or PM Narendra Modi doing the garba. Prateek Jain of the Indian Political Action Committee or I-PAC says he is concerned about the “weaponisation of false information”. Bivas Chatterjee calls the same thing “the charisma of misinformation”.

Sarkar had spoken of AI being used to make a scuffle look like a riot, even give something a communal angle. “If you slap someone once, AI will convert it to 20,” he had added.

One expert who did not want to be named said, “Some of the videos of Sandeshkhali are doctored. AI has been used to change the narratives or arrange or edit them to make them presentable. I am not saying that the incidents are fake but the videos have been manipulated.”

Chatterjee says, “In a country like India with a population of 1.4 billion, fake news or deep fakes will spread faster than fire. It is impossible to stop them and they most definitely can impact elections.” A deep fake has been defined as “an artificial image or video (a series of images) generated by a special kind of machine learning called ‘deep’ learning”.

According to the Global Risks Report 2024 by the World Economic Forum, AI-generated misinformation and disinformation is something to be reckoned with and India ranks first on a list of nations that are most at risk. The report reads: “...over the next two years, the widespread use of misinformation and disinformation, and tools to disseminate it, may undermine the legitimacy of newly-elected governments”.

Visuals, be it photographs or videos, have the greatest propaganda or mischief potential. “AI video/audio can be made by anyone,” says Pahwa. He continues, “If a (problematic) video is released less than 24 hours before a constituency is going to polls, it might be difficult to detect that it is false or AI generated, and voting may be affected.”

Tejasi Panjiar, associate policy counsel at Internet Freedom Foundation, which is an Indian digital rights organisation, says, “AI-generated synthetic media such as deep fakes can imitate the tonality of a person quite accurately. For individuals who are not forensic experts or fact checkers, such pieces of content may easily pass the check of veracity.”

It is Panjiar who points out that policymakers are so far issuing notices to social intermediaries and holding them responsible for spreading deep fakes. She says, “Political parties should use AI responsibly and issue disclaimers whenever they share AI content instead of letting people guess what is wrong or right.”

Social media websites and intermediaries typically enjoy something called “safe harbour”. This basically means they do not have any legal liability for any post. But as per the latest amendment in 2023 to IT Rules 2021, they have to be vigilant and remove/delete any inappropriate content, failing which they will no longer enjoy safe harbour.

But just as one cannot depend on the transparency of political parties, one cannot depend on any threat of no-safe-harbour for making our polls AI-proof. So what happens? What are we to do?

Pahwa is pragmatic. He says, “You cannot go back in time or turn off technology. It is best that our democratic systems and our electoral processes become more resilient to combat them instead.”