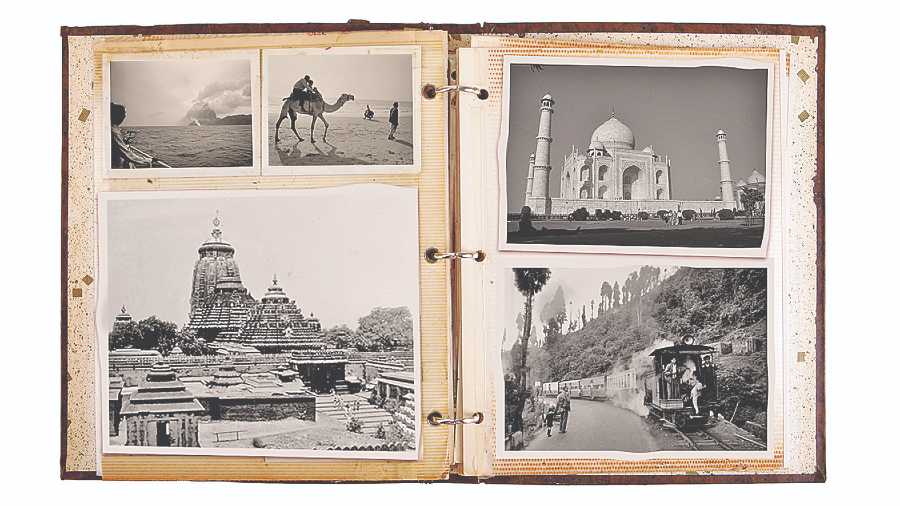

The Bengali traveller is ubiquitous. Whether you are visiting Ladakhi monasteries or Rajasthani palaces, the odds are you will be sharing them with a few Bengalis. No matter if you love the mountains or the beach, you are sure to have them join you on vacation. Chances are whether it be watching the Northern Lights around the Arctic Circle or visiting a tiny African country to catch a total solar eclipse, you will run across one. They climb mountains, go trekking, enjoy jungle safaris, loll on beaches, visit heritage sites.

To begin with, the Puja season was traditionally the time Bengalis would set out on their travels. First, because it was vacation time for the job-bound Bengali and, second, because the railways used to give hefty discounts on fares during this period. So much so that in places as far-flung as Kashmir and Sikkim, October is known as “Bangali season” by those in the tourism industry.

But much before rail tracks were even laid in the country, Bengalis were travelling. To get to the bottom of the why — or nearabouts — it is necessary to put a date to the earliest such expeditions.

The earliest known travelogue by an aam Bengali dates back to 1770 and was written by Bijoyram Sen, a kabiraj in the service of Krishnachandra Ghosal, the raja of Bhukailash — in the Kidderpore area of Calcutta. Tirthamangal is really an epic poem that describes the journey undertaken by Ghosal from his home in Kidderpore to Kashi by

boat. It describes all the places visited as well as the people he met. Ghosal’s younger brother Gokulchandra paid for the journey — a princely sum of a lakh, Sen has written. Gokulchandra was dewan to the second governor of Bengal and historians speculate that Ghosal’s pilgrimage was actually undertaken to study the lay of the land for Gokulchandra’s East India Company masters.

Kashikhanda was written by Ghosal’s son and heir Joynarayan. It detailed his days in Kashi and was published in 1809. The other surviving travelogue from those times was published in the form of serialised articles in Sangbad Prabhakar, the first Bengali newspaper. It detailed the journey of the founder-editor of the paper and well-known poet, Ishwarchandra Gupta, in the northwestern provinces of India.

These apart, there was the very first modern travelogue in Bengali, Kashmir Kusum, by Rajendra Mohan Basu. It was published in 1875. The other thorough book about a place — in this case a city — was Bombai Chitra by Satyendranath Tagore, one of the first Indian ICS officers.

Once transportation became widely available, more people started travelling,” says Barid Baran Ghosh, president of the Bangiya Sahitya Parishad.

By this time, Bengalis had spread all across the country, working for the British as well as local rulers. Prakash Chandra Roy moved to Bankipur in Bihar from his birthplace in Murshidabad’s Behrampore in the 1870s to work as an excise inspector. After finishing his medical studies in Calcutta, Jyotirindranath Sen moved to Kathmandu at the end of the 19th century. Jyotirmoyee Devi grew up in Dehradun in the early 1900s because her uncle, the head of her family, worked at the Survey of India headquarters there. Her daughter Nanda spent her formative years in Pisca, now in Jharkhand, where her father worked in the railways.

When Bimal Mukherjee started off on his way around the world with three friends and four cycles — a journey he chronicled in his book Dui Chakae Duniya or the World on Two Wheels — at the end of 1926, he usually found a Bengali family to host him. There was legal luminary S.R. Das in Delhi, who sang their praises to Viceroy Lord Irwin and influenced him to invite them over for tea; ICS officer S.N. Bannerjee, who was guardian to the 14-year-old king of Jaipur, ensured they were royal guests; and Tarachand, prime minister of Bharatpur, whose parental name was Tarakchandra Chowdhury.

Work wasn’t the only reason Bengalis got around. As early as 1848, Kalikrishna Sen Majumdar, who was a scribe in the office of the Barisal zamindar, went to Puri, Mathura and Kashi on foot. As did Ishwar Chandra Bagchi, who undertook many a pilgrimage from Kamakhya in Assam to Baidyanath Dham in present-day Jharkhand, or so we learn from his book Tirthamakur published in 1891.

What prompted the Bengali love of travel?

“The physical sense of wanderlust cannot exist without the widening of mental horizons,” says Jayanta Sengupta, secretary and curator of Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall. “And the Bengali community always had zenology — the awareness of foreign lands.” How else did Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay nail such a lived-in description of Africa in Chander Pahar, published in the late 1930s, without ever having ventured outside India?

This knowledge came from both literature and travelogues. “There is a culture of manash bhramon (or armchair travel) in Bengali,” says Mahasweta Samajdar. “My father, Amarendra Chakravorty, started Bhraman magazine to cater to that.” He published travelogues old and new, detailing experiences in Antarctica as well as 14th century Delhi, and found plenty of takers. But a century before Bhraman was launched in 1993, magazines such as Mashik Bharatbarsha were already carrying travel writings, such as articles by its editor Jaladhar Sen, who travelled in the Himalayan region between 1887 and 1891.

“There is a rich heritage of travel literature in Bengali. This is probably unique to this language,” says Ghosh. It only increased in volume as Bengalis spread across the country for work. Sanjibchandra Chattopadhyay, brother of novelist Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, retired as a deputy magistrate for the British. He turned his time spent in what is now Jharkhand into the lyrical book Palamau that mixes travel writing with fiction.

Then, in the mid-20th century, there was the phenomenon called the Ramyanee Beekshya, a travelogue with the soul of a novel. When Subodh Kumar Chakraborty wrote the first one on South India, he did not know how popular they would become. He went on to write 18 more volumes on Assam, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, Kashmir and so on. An employee of the Eastern Railways, he vacationed twice a year and published a book detailing each. “It was a tradition to read the Ramyanee Beekshay volume on the area you were going to visit if you hadn’t read it,” says Tapesh Sen, 84, retired public servant who has visited most of India from Kashmir to Kanyakumari.

In 1892, Swami Vivekananda told his friend Shankarlal, “If we really want to reconstitute ourselves as a nation, we have to freely mingle with other nations. So, travel whenever you can.” Sounds like more than one person was listening.