During the first few days of the lockdown, Raghbir Singh and some others served 500 meals in and around south Calcutta. Thereafter, they lost count and it was never the point in any case.

The 30-year-old, who works part-time as a real estate dealer and also helps out with the family car rental business, is not new to relief work; he has helped during the Kerala floods of 2018 and the Assam floods of 2019. He says, “When the lockdown was announced, we knew our relief work would have to be ramped up. Since Day 2 we started cooking dal-chawal daily at the Garcha gurdwara and distributed it to people living on pavements and makeshift houses by the roadside.” Volunteers also went around city hospitals such as Chittaranjan Hospital in Park Circus, R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital in Shyambazar and Calcutta Medical College on College Street with food packets for patients’ kin.

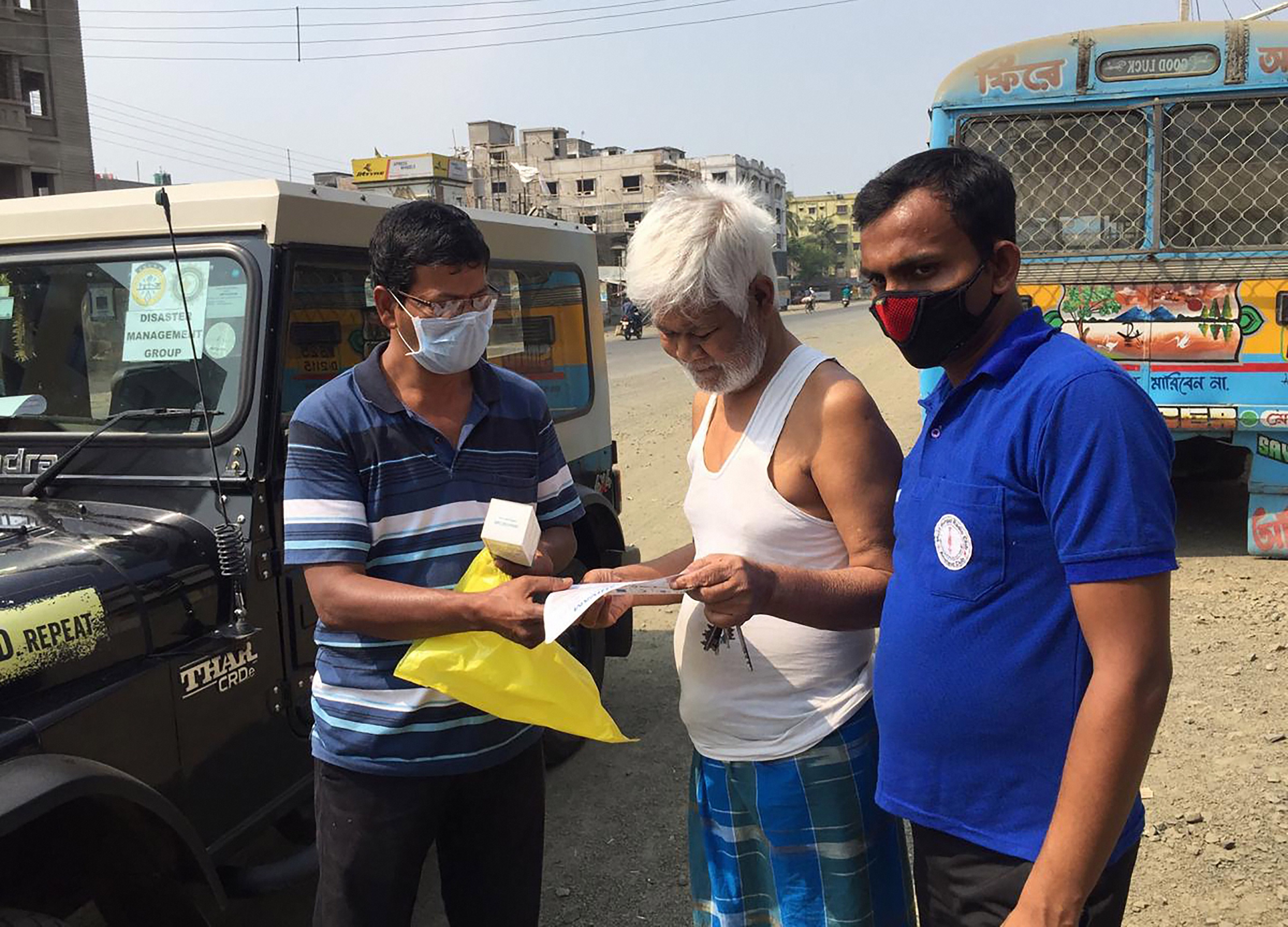

After the first few days, volunteers of Khalsa Aid, a UK-based humanitarian relief organisation, with the help of south Calcutta’s Sri Guru Singh Sabha Gurdwara, started distributing rations — flour, rice, pulses, sugar, salt — to those in need. They had those as well as cooked food home-delivered too. Raghbir has also been on National Highway 6 a couple of times since the lockdown to hand out bottles of drinking water, biscuits, puffed rice and juice to migrants walking home.

It is difficult to get phone time with Raghbir. Their garage has been shut, and he has been immersed in seva round-the-clock. It entails serving cooked food all day and then driving around the city in the evening delivering household staples.

Raghbir says amidst all this frenetic activity, every successive day he has seen a different side to humanity. “I saw first-hand how difficult it was for the daily-wage earners to survive. They wanted to earn money and some refused to accept the food we distributed.” He talks about others, middle-class folks who first fought shy of seeking assistance, but approached him when he was by himself. “I met so many people who feel that because they are poor, they do not exist for the government,” says Raghbir in muted tones.

On the night of Cyclone Amphan, Raghbir and others from Khalsa Aid got their cars out and drove around the city looking for the stranded and those in need of help of any sort. “We came upon more than one ambulance — carrying patients and kin — stuck on the road. There were uprooted trees all around, impeding movement,” he says.

The morning after brought to light the scale of devastation. Keeping in mind the disrupted power supply and lack of running water across the city, the sevaks went about collecting more groceries. On the first day, they distributed food and water among 400 people, the next day that number doubled and the day after that, it tripled.

Funds to continue this outpouring of support continue to come from private organisations and individuals, most of who prefer to remain nameless.

The night of the cyclone, Raghbir and other volunteers had received instructions

to be on Ground Zero and report the situation so they could start relief work immediately. He says, “We were unable to reach places such as Namkhana and Kakdwip in South 24-Parganas as the roads were completely blocked; so we focused on Calcutta until the roads were cleared.”

On May 25, the group set up their base camp in Diamond Harbour, also in the South 24-Parganas. Raghbir says, “Most of the people had kutcha houses and the cyclone had blown them away. We had carried along plastic sheets; we made canopies for temporary shelter.” The kitchen in Diamond Harbour fed the locals and also many in the Sunderbans and Sagar Island.

Did Raghbir ever fear that he would contract the coronavirus? Does it play on his mind even now in the face of continuing relief work? By way of reply, a photograph lands in the chat window. A close-up of a Khalsa Aid T-shirt with a message emblazoned on it. It reads — Recognise the whole human race as one. Raghbir says, “There is magic in the uniform.”