On the first Wednesday of every month, I step out of Ajoynagar Colony 1 in south Calcutta where Bratati Chakraborty lives and walk with her to the fair price shop at Ajoynagar More. Unfailingly, there is a long queue and a cross-looking man at the end of it. When it is Bratati’s turn, she thrusts me before him while a wiry old man measures out a couple of kilos of rice, two kilos of wheat, a kilo of sugar, a kilo of pulses and a litre of kerosene oil.

The man at the desk notes down something in a red coloured copybook and I am relieved to be handed back to Bratati and be out of his sweaty palms. She puts me into a plastic folder with utmost care, puts the folder into her polythene bag and gets into a battery-operated rickshaw. She has to shell out Rs 20 as fare.

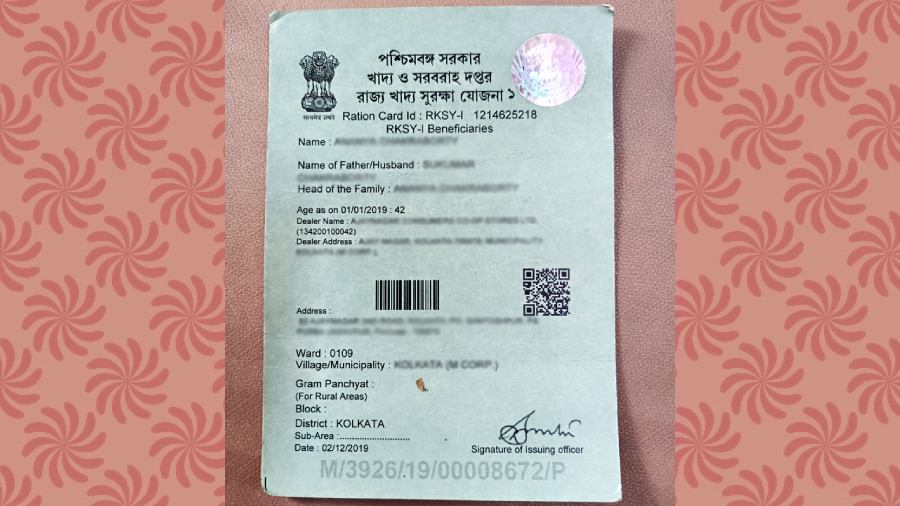

I am the green ration card issued by the food and supplies department of the state government under the state food protection scheme.

For Bratati, I am also proof of her identity. I bear her name, her husband’s name, her age, her address, the specifics of the municipality ward she belongs to, the local police station and the local panchayat, the area pin code and the state name. At the bottom of the card is my own date of birth and my 16-digit identity.

Once back home, Bratati hangs the bag from a peg right next to her bed. This is the best and safest place — away from the squabbling preteen children, dust, dirt and humidity.

Rationing of food grain had started sometime in the early 1940s. I have heard Bratati’s grandfather talk about the time when coupons were issued by the British government during World War II as there was a shortage of food grain. Those days the fair price shops distributed grain, sugar and kerosene against coupons. Kerosene was needed for the lanterns and also for the cooking stoves.

After Independence, my ilk — ration cards — came in new hues. Every state used a different colour. In West Bengal, where Bratati’s family has always lived, we were at first printed in white, then in red. “The red one used to look like a bank passbook,” says Bratati, but she does not know what prompted the change in colour. The colour changed to green at the turn of the century, before the state government did.

The rationing system is a joint effort of the Union government and the state governments. While the states are in charge of the distribution of grains, the Centre procures the essentials.

Today, in West Bengal there are three kinds of cards. One is the white card. It is what everyone has irrespective of income. “On this card, rice can be purchased at Rs 13 a kilo and wheat Rs 9 a kilo,” says Kuheli Halder, who is also a resident of Ajoynagar. She uses her neighbour’s white card. Her own green card is with her in-laws who live in a village in South 24-Parganas. In a pre-onenation-one-ration-card India, they used her green card to collect subsidised food grains.

And then there is my youngest kin, the white and blue digital ration card. It was introduced in 2016. I have heard it said how this came linked to the Aadhaar number and Kuheli could no longer collect ration with her neighbour’s card.

Now, in suburban Bengal the digital card is popularly known as the five-kilo-card. During the pandemic, people with blue digital cards got two kilos of rice and three kilos of wheat per month.

Kuheli also availed of the benefits. I had heard her boasting how she got five kilos of rice, five kilos of wheat, one kilo pulses, one kilo black gram and a kilo of onion for the first three months of the nationwide lockdown in 2020. All free of cost.

I don’t know what to make of this change in colour. For whose convenience is this? Not for the people’s, if you ask me. I am told that it is for the ration dealer’s convenience. They see the colour and know what to give and how much to give to each cardholder.

And that is why Bratati does not need to ask for anything at the fair price shop. She can wave me at the counter and get her bag full of necessities. But this Wednesday she is not happy; in fact, it is a long queue of unhappiness and uncertainty. There is no kerosene at the fair price shop. In the market it costs Rs 90 a litre.

How will Bratati light her stove, prepare the meals? How will all of them? Kerosene costs only Rs 40 a litre in fair price shops. Already, LPG has become costlier than her monthly electricity bill. A few days ago she had discontinued her cable subscription to save money.

Bratati puts her little bottle back in the jhola, empty. “Since May 2022, kerosene has gone out of stock from the fair price shop,” I hear her neighbour say. He adds, “They are not even giving the Rs 2 kilo wheat. Free ration declared by the state government has ceased to exist.”

What is going to happen to me, I wonder. Will I be of no use any longer? With a heavy heart, I walk back with Bratati. This time we did not take our usual rickshaw ride.