Thirty-third US President Harry S. Truman, who succeeded Franklin D. Roosevelt and implemented the Marshall Plan to rebuild the economy of Western Europe, had once said: It’s a recession when your neighbour loses his job, it’s a depression when you lose yours.

In the year of pandemic, the impact of recession was felt by almost every Indian — both in rural and urban areas — in the last 10 months or so as people suffered because of lower income in the farm sector while job losses and salary cuts wreaked havoc in urban centres.

When Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman rose to present her budget proposals for 2021-22 on Monday morning — against the backdrop of expectations that the country’s gross domestic product would shrink 7.7 per cent in the financial year ending March 2021 — she had the challenge to reset the economy.

At the very beginning of her speech, she made it clear that she was aware of the task at hand and said: “This budget provides every opportunity for our economy to raise and capture the pace that it needs for sustainable growth.”

By the time she ended her proposals in little less than two hours — quicker than what most analysts had expected — the Sensex got buoyed by 5 per cent, the best budget day gain since P. Chidambaram’s dream 1997 budget. No bad news in the budget, was the sentiment in the equities market, which brought loud cheers from the bourses.

While market sentiment is undoubtedly an important indicator of a budget, it cannot be the only yardstick to assess proposals contained in a budget. The government’s commitment to common people — which gets reflected in terms of allocation of resources — is also important in a poor country like India where inequality has been on the rise.

Sitharaman may have passed the test of the market, but a closer scrutiny of the numbers reveals that the masses, who had to bear with the fallout of the biggest contraction in the economy post-Independence, were not the priority when the budget proposals were being drawn up in the finance ministry.

In the year of pandemic, survival was the priority and ordinary people — from migrant workers in farm sectors to those engaged in the unorganised sector in urban centres — braved the consequences of one of the most stringent lockdowns across the globe.

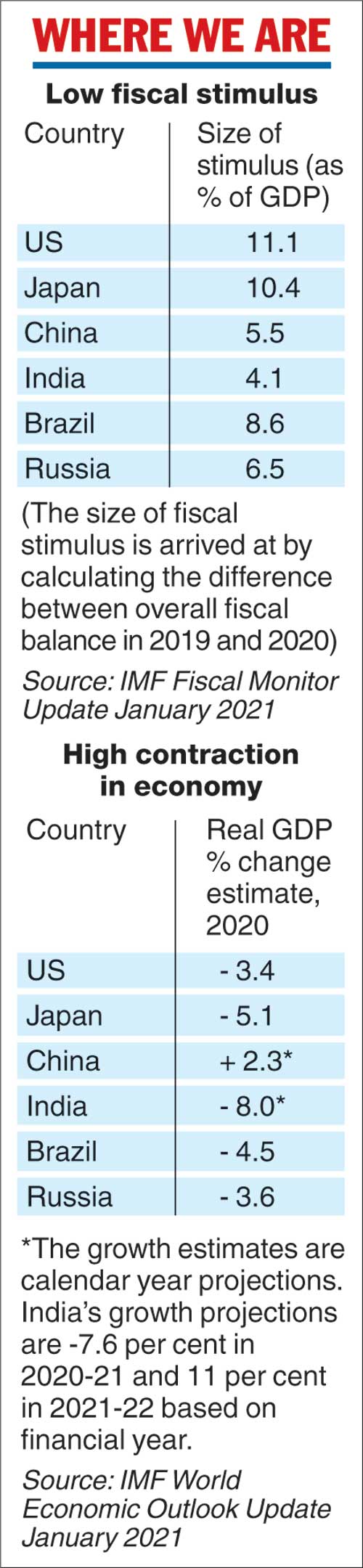

The authorities across the world announced several fiscal measures to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 by doing away with the obligation of complying with deficit targets. Take for instance the case of Brazil, which rolled out temporary income support to vulnerable households like transferring cash to informal and low-income workers, forward the 13th pension payment to retirees, advancing payments of salary bonuses to low-income workers, extending employment support to those losing jobs and even offering temporary tax breaks. More than 8.6 per cent of the GDP was spent on income of workers, bringing these measures, and the Brazil economy is expected to contract by 4.5 per cent.

In her budget speech, Sitharaman claimed that the Narendra Modi government, through three tranches of Atmanirbhar Bharat packages, including measures taken by the RBI, offered a stimulus of about Rs 27.1 lakh crore, amounting to 13 per cent of GDP, to give people a better deal in the time of the pandemic.

The quantum of the stimulus has been questioned as the government’s attempt at infusing liquidity, through the RBI’s interventions, cannot qualify as fiscal measures. That’s why the IMF Fiscal Monitor Update has pegged the size of the stimulus to barely 4.1 per cent of the GDP — one-third of the government’s claim — which is much lower in comparison to other countries. (See chart)

The expenditure side of the budget shows that instead of the budget estimate of Rs 30.4 trillion, the government is likely to spend Rs 34.5 trillion in 2020-21. According to budget documents, the additional Rs 4 lakh crore was spent on food and fertiliser subsidies, medical expenses and on rural employment.

Had the government listened to the suggestion of economists and transferred money directly to migrant workers or those losing jobs in the unorganised sector in urban areas, the expenditure would have been more, but it could have had a better effect on the economy and the extent of the contraction could have been lower.

While presenting her budget proposals, Sitharaman has projected 14.4 per cent nominal growth in the economy in the next fiscal. The budget proposals are, however, sketchy in explaining how this turnaround — among the highest in the world — would be achieved. The expenditure projections reveal that the government would spend barely Rs 34,000 crore more next fiscal. Will it be enough to reset the economy? Will such modest expansion in expenditure bring back the jobs people lost during the time of the pandemic?

It’s clear that the finance minister is banking heavily on the private sector to come forward and play a key role in the economy’s turnaround. In 2019 September, Sitharaman had offered India Inc tax breaks in anticipation that they would invest, which, in turn, would fuel growth in the economy. In the absence of any cues from the government, India Inc chose not to invest.

The situation is unlikely to change and the projection of a revival may remain only in the budget papers.