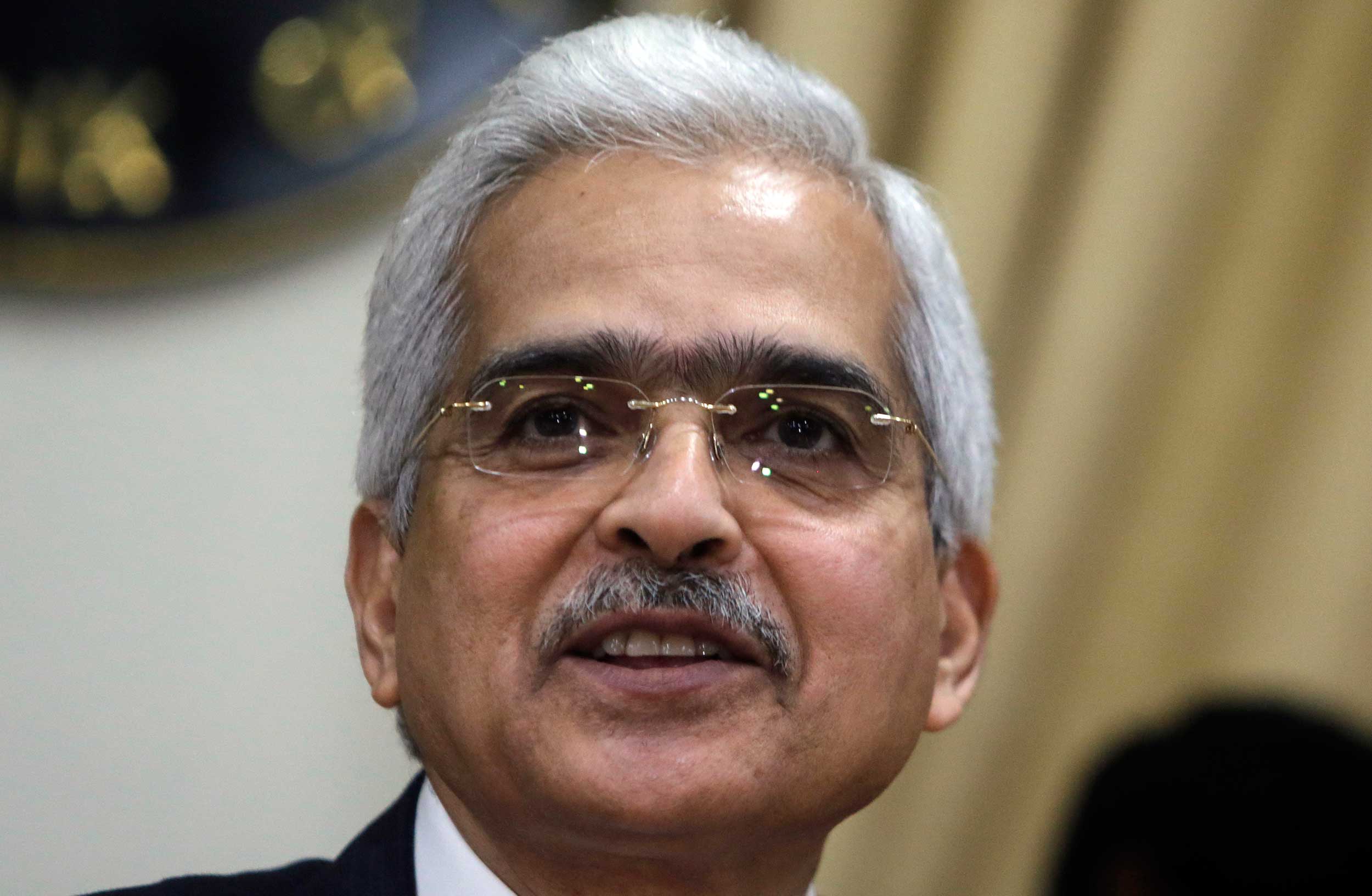

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Shaktikanta Das has suggested a more dynamic approach to policy rate tweaks at a time the global financial crisis is exposing the limitations of conventional and unconventional monetary tools.

The former bureaucrat, who is now the 25th governor of the RBI, has come up with the idea that central banks should not go by the set quantum of 25 basis points (or multiples thereof) when it comes to revising interest rates even as conventional central bankers and economists may scoff at the idea.

In other words, the policy rate changes can be more dynamic and could be even changed by 10 or 15 basis points, depending on the scale of the central bank’s stance.

Banks generally announce a stance of tightening, neutrality or accommodative to guide the markets and the public on the future course of policy along with any changes in the rate.

Delivering a special address on the sidelines of the annual Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Washington on Friday, Das said the unconventional monetary policies of advanced economies have resulted in “risks and spillovers” for the emerging markets.

The limitations

In his speech, titled “Global Risks and Policy Challenges facing Emerging Market Economies”, he observed that the global financial crisis has exposed several limitations of conventional and unconventional monetary policy tools and in “despair, some have turned to the heterodox evolution of ideas that are being practiced as modern monetary theory’’.

According to Das, monetary policy must touch the real economy, spur investments and maintain monetary and financial stability.

Therefore, the time has come to think out of the box, including challenging the conventional wisdom.

“One thought that comes to my mind is that if the unit of 25 basis points is not sacrosanct and just a convention, monetary policy can be well served by calibrating the size of the policy rate to the dynamics of the situation and the size of the change itself can convey the stance of policy. For instance, if easing of monetary policy is required but the central bank prefers to be cautious in its accommodation, a 10-basis-point reduction in the policy rate would perhaps communicate the intent of authorities more clearly than two separate moves.”

“Likewise, in a situation in which the central bank prefers to be accommodative but not overly so, it could announce a cut in the policy rate by 35 basis points if it has judged that the standard 25 basis points is too little, but its multiple, that is 50 basis points is too much,” he observed.

His remarks come at a time there are expectations that the RBI may again cut the policy repo rate in June with inflation remaining below its medium-term target and growth being patchy as reflected by the dismal industrial output number of 0.1 per cent for February.

Since his arrival in Mint Street last December, the RBI has reduced the repo rate by 25 basis points each on two successive occasions.

Global challenge

Stating that the management of global spillovers poses a formidable challenge for emerging market economies, Das said a truly global financial safety net remained elusive as in this age of mobile capital flows, consequences of their arrivals, sudden stops and reversals are to be borne nationally.

As a result, emerging market economies (EMEs) are typically at the receiving end when global spillovers flare up, he said, adding that they have no recourse but to build their own forex reserve buffers.

Paradoxically, the accumulation of reserves has become stigmatised, including with labels such as “currency manipulation”, he rued.

“As I see it, we may be unintentionally setting the stage for several EME currencies to break out and challenge the hegemony of the dominant reserve currencies. There is a need for greater understanding on both sides,” Das said.