We’ve been through a decade of economic ups and downs. But as we wait for the first budget of this decade, it’s clear it’s been a long while since the numbers looked as uniformly bleak.

Economic growth is the weakest since 2008. High food prices have driven inflation to six-year highs. And revenue collection growth is at its lowest in a decade. The government had projected a 25 per cent hike in net tax collections for 2019-20 but until November tax revenue had only risen by 2.6 per cent.

Even if tax collections pick up in the final four months of the financial year to March 31, 2020, it won’t be enough to plug the shortfall.

That leaves Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman precious little to play with to boost the stuttering economy. The government’s still talking about its 2024 target of being a $5-trillion economy, up from $2.7 trillion now, even though our current growth rate is nowhere near fast enough to get us there. (We’d need to grow by 9 per cent to 10 per cent a year to hit that $5-trillion goal).

The government is now forecasting growth will come in at 5 per cent which would be lowest since 2009 when the global financial crisis shook the world economy.

The IMF, which had originally predicted 6.1 per cent growth for India in 2019, has revised that downwards to 4.8 per cent, the lowest in nearly six years (India’s poor performance was the key cause of the IMF lowering world growth estimates in 2019 from 3 per cent to 2.9 per cent. For 2020, it reckons that India could grow at 6.1 per cent).

So given the fiscal challenges, what can the cash-strapped government do to spur the economy and tackle falling consumer confidence and unemployment at a 45-year high?

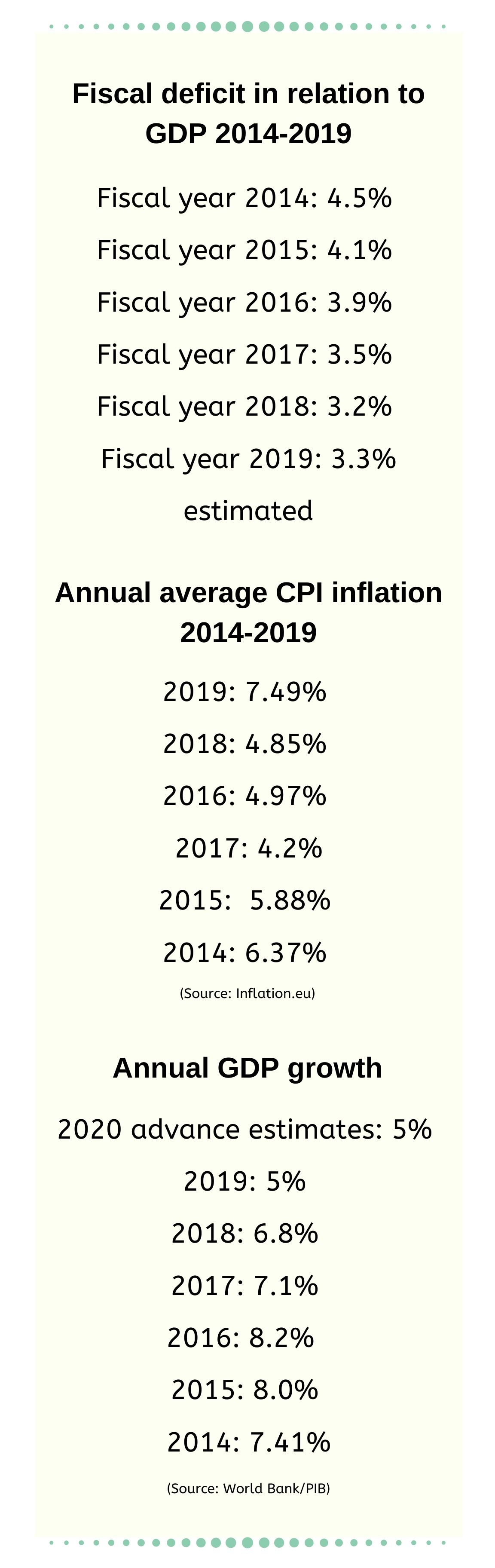

It’s already widely accepted the government’s likely to miss its fiscal deficit target for the current fiscal year of 3.3 per cent and hike its target to as much as 4 per cent for the next financial year, to give itself more financial leeway to boost the economy.

All these economic challenges come as the world economy is facing as-yet unknown fallout from the Coronavirus, and the US-China trade war has put a dampener on global trade. And while the government is seeking to spur expansion, it’s also having to contend with the fact that the banks are still seeking to clear their balance sheets of non-performing loans.

The government has already made a string of moves to counter the downturn, including cutting corporate taxes, easing foreign direct investment rules in retail, manufacturing and coal mining and embarking on a major privatisation push.

But so far, economic indicators are still pointing the wrong way. Indians will be looking to Sitharaman’s budget to revive India’s much vaunted “animal spirits” and help Asia’s third-largest economy turn the corner.

Here are the 2014 to 2019 numbers that tell the story

The Telegraph Online

Grim indicators

- India will struggle to achieve 5 per cent GDP growth in 2020 - Economist Steve Hanke, Johns Hopkins University

- At 7.5 per cent in 2019-20, nominal GDP, which is calculated current prices of goods and services, is expected to be the worst since 1978 and far below than government's earlier projection of 12 per cent. (Source)

- Manufacturing is likely to clock 2 per cent growth in 2019-20, the lowest in 13 years (Source)

- Construction, one of the largest employers in the country, is expected to expand at a six-year low of 3.2 per cent -- a sharp decline from 8.7 per cent for 2018-19. (Source)

- Investment is forecast to grow at less than 1 per cent -- the lowest since 2004-05 (Source)

- Passenger vehicle sales declined 13 per cent on year - contracting for the eleventh straight month in December (Source)

- India's unemployment rate rose to 7.5 per cent during September-December 2019 quarter, according to data released by think-tank Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE)