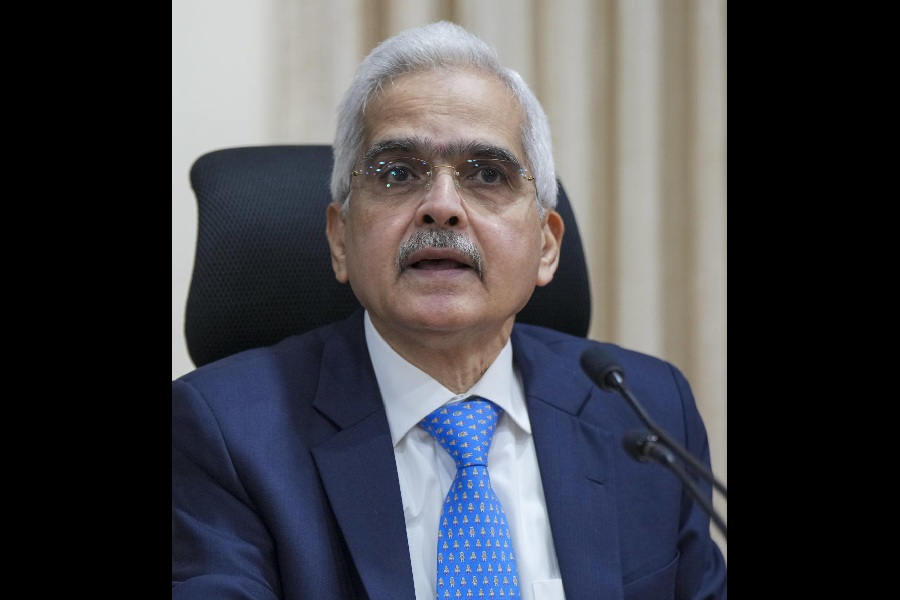

Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das has received no word from the Narendra Modi-government on the widely-anticipated extension of his tenure that ends on December 10.

The nerve-wracking wait means the RBI governor will go into the three-day meeting of the monetary policy committee (MPC) on Wednesday under intense pressure from the government and industry to cut the policy-setting repo rate for the first time since May 2020 — and not entirely certain whether the extension of his tenure hinges on the call that he and his cohorts make.

Between May 2022 and February 2023, the central bank winched up rates six times from 4 per cent all the way up to 6.50 per cent before pressing the pause button on a rate rejig.

Das and deputy-governor Michael Patra, who is due to retire in January, have both set their faces against an early rate cut, arguing that they have a clear mandate to bring down inflation to a median level of 4 per cent.

Under the inflation-targeting framework for the conduct of monetary policy that was adopted in 2015, the MPC must ensure consumer price inflation stays within a tolerance band of 2 to 6 per cent.

Retail inflation in October soared to 6.21 per cent, largely driven by food inflation which has been hovering at 10.87 per cent.

The government, however, wants the RBI to cut interest to kickstart a cycle of growth especially after the National Statistics Office (NSO) shocked the nation with the chilling announcement last Friday that the economy had stuttered with GDP growth in the second quarter ended September 30 tumbling to a seven-quarter low of 5.4 per cent.

The government has tried to be blasé over the unexpected setback with the chief economic adviser V. Anantha Nageswaran insisting that this was a mere blip and the country would be able to buck the slowdown.

“India’s potential GDP growth is in the range of 6.5–7 per cent, and we should be able to achieve it on the back of what we have done over the last 10 years — whether it is in terms of augmenting physical infrastructure or achieving financial inclusion,” he said.

But what he did not say is that the government is willing the RBI to cut rates — and quickly. Both commerce minister Piyush Goyal and finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman have either bluntly or subtly tried to send out a message to governor Das and his fellow members in the MPC to look past food inflation for once and trim the repo rate.

Others have joined the clamour for a rate cut. The slowdown should be a “wake up call for the RBI”, said Radhika Piplani, an economist with DAM Capital Advisors.

“The next rate decision is live for a policy action and will be keenly watched for reasons behind the GDP miss,” she added. “If the central bank doesn’t ease now, it could be forced to compensate with a larger-than-expected cut in February.”

“India is indeed slowing down and the RBI is in quandary,” Suresh Ganapathy, head of financial services research at Macquarie Capital Securities, said in a note on Monday. “However, with the recent GDP data, there will be pressure on the RBI to cut rates by February 2025” as inflation remains high, he said.

Some economists argue it may be too late to wait till February. Gaura Sen Gupta, an economist with IDFC First Bank Ltd., said she wouldn’t “recommend waiting for February to cut policy rates, given the transmission lags”.

Patra had argued that the RBI was right to target inflation rather than try to pump prime the economy by cutting rates.

In an article on the State of the Economy in the RBI’s monthly bulletin for November, the deputy-governor said: “Inflation is already biting into urban consumption demand and corporates’ earnings and capex. If allowed to run unchecked, it can undermine the prospects of the real economy, especially industry and exports.”

That is the sort of talk that brings a sort of edginess to the inflation versus growth debate. And the way that the MPC answers that question could well decide who will get to helm the central bank.