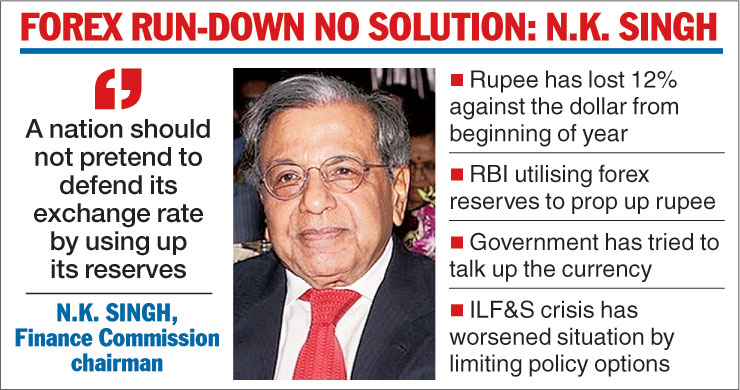

Finance Commission chairman and former revenue secretary N K Singh feels the lesson to learn from the 1990s in tackling the current economic crisis is not to keep defending the rupee by using up foreign exchange reserves.

“The lesson we should draw from the 1990s is that a nation should not pretend to defend its exchange rate by using up its reserves. Thailand had a comfortable reserve of $60-$70 billion in 1996-97, they ran it down in just eighteen months trying to defend the baht,” Singh, a former economic affairs secretary in Manmohan Singh’s original economic reforms team of the 1990s, said in an interview to The Telegraph.

A foreign debt default in 1997 by one of Thailand’s biggest property developers and the collapse of the country’s largest finance company saw speculators driving down the value of the Thai currency.

The Southeast Asian nation’s central bank punted almost all its foreign exchange reserves in off-balance-sheet currency transactions to defend its currency, but without much success.

The rupee has been sliding through the month of September 2018 and has fallen as much as 12 per cent against the dollar since the beginning of this year. It has done even worse against the pound, sliding nearly 21 per cent since March when it traded at 79.51 to the British currency.

The RBI has aggressively drawn from its own reserves in a bid to defend the rupee. The country’s foreign exchange reserves stood at $401.79 billion in the week ended September 21 compared with a record high of $426.03 billion in the week ended April 13, a dip of more than $24 billion.

The fall in the value of the rupee has also prompted the government to try talk up the market.

However, so far, the measures adopted have not been able to offer much comfort to either the rupee or the government. Foreign investors have remained net sellers of local debt. The Sensex has been badly singed, scaring investors.

The forced takeover of IDBI and the defaults by India’s large non-banking finance company IL&FS also did not help to calm the panic on the bourses.

“India’s economy is in a far better situation now, on a firmer footing but at the same time compared to then and to the Lehman Brothers crisis in the last decade, we have more challenges as we are far more globalised,” said Singh, who is currently working on his memoir of the Manmohan-to-Vajpayee years.

“Inter-dependence with other major economies has both opportunities as well as challenges. The challenge is to maintain macro-economic stability in a difficult global situation,” the former civil servant-turned-parliamentarian added.

The government had earlier this month decided to adopt a multi-pronged approach to tackle the continued fall in the rupee which would involve monetary policy changes and faster intervention in the foreign exchange market, encouragement to rupee bonds to sap up more dollar reserves and trade measures to cut India’s import bill.

A fear of contagion because of a massive fall in the value of the Turkish lira has seen most emerging market currencies, including the renminbi, the rouble, the South African rand, the Brazilian rial and the Indonesian rupaiyah battered.

The fall not only makes India’s energy imports costlier, it also means the country has to shell out more in paying foreign currency short-term debt.

India’s oil import bill is expected to go up $25 billion, while the cost of servicing short-term borrowings would go up $9.5 billion. The latest balance of payments data show that India’s current account deficit came in at 2.4 per cent of GDP in the first quarter of this fiscal.

“The government has shown commitment to fiscal rectitude … (but) it is ironic that the current economic problems have been preceded by years of fiscal expansion,” said Singh.

India’s debt to GDP ratio remains high at about 70 per cent. The total public debt rose to Rs 63.35 lakh crore till June, up 3.6 per cent over the previous quarter, according to government data released at the beginning of September.

However, Singh, like most Indian bankers and economists, feels that the defaults by IL&FS and the bad loan crisis faced by state-PSU banks is “not India’s Lehman Brothers moment”.

“The contagion effect (of the IL&FS default) can be contained… we have a far stronger financial system now and can handle this deftly,” the finance commission chief said.