Investors’ expectation from Union Budget 2020 is high, especially when the finance minister has already started taking measures to boost the economy. Corporate tax rates have been brought down to 22 per cent or 15 per cent (plus applicable surcharge and cess) for different categories of companies to make India a low corporate tax jurisdiction.

However, the regime for taxation of dividend remains an issue. One needs to evaluate if it needs to be continued because corporate tax along with dividend distribution tax (DDT) still keeps India in the fairly high tax category in the minds of the investor.

DDT at the rate of 10 per cent was introduced in India in 1997. The intention behind the shift from the erstwhile regime of taxing the shareholders on dividend income was to make the process of collection of taxes better and to eliminate cumbersome paperwork that the shareholders had to undergo to claim creditor refund of tax deducted at source (TDS).

The DDT rate has moved upwards over the years and now stands at 20.56 per cent (grossed up). Further, Finance Act, 2017, introduced Section 115BBDA whereby resident taxpayers (non-corporate investor/promoters) earning dividend income of more than Rs 10 lakh are required to pay income tax additionally at 10 per cent (plus applicable surcharge and cess) on the dividend received.

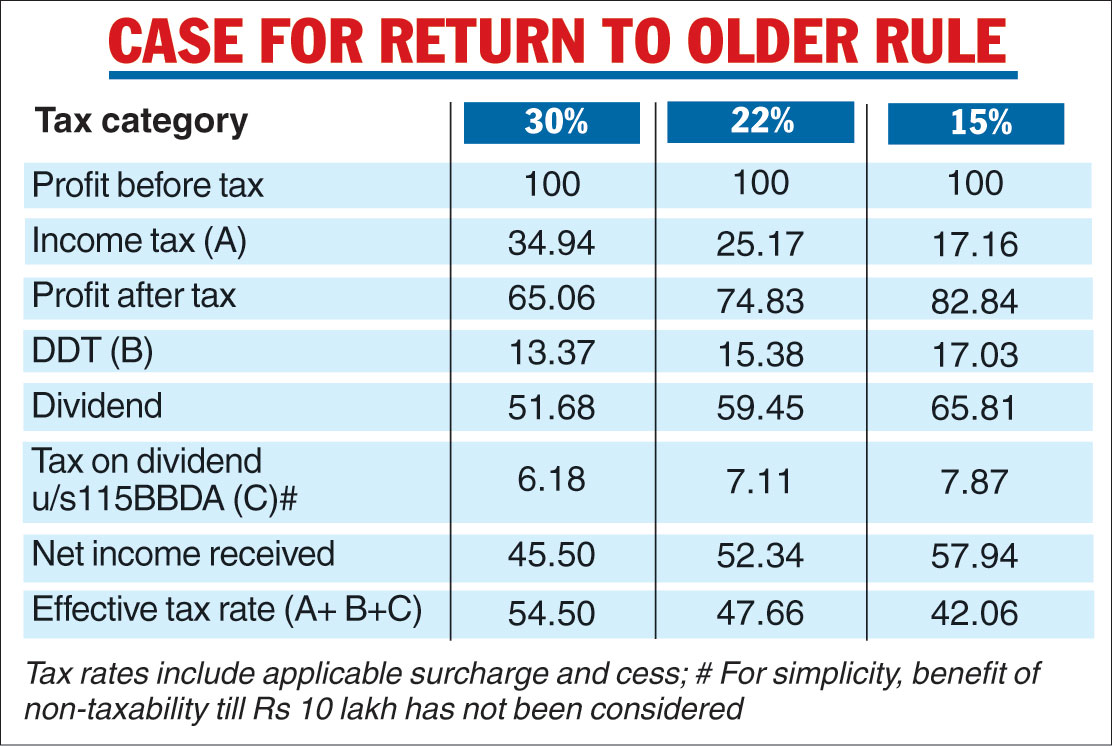

So, under the current tax regime, profit of a company suffers three levels of income tax before it comes to the disposal of a resident non-corporate shareholder. At the maximum level, a profit of Rs 100 earned by a company is subject to a tax of 54.50/47.66/42.06 per cent, leaving 45.50/52.34/57.94 per cent with the non-corporate investor depending on the tax rate that applies to the company (see chart). Individuals who are below the maximum tax exemption threshold also have to pay tax on dividend through DDT.

In the case of corporate shareholders, there are two levels of taxation aggregating 48.32/40.55/34.19 per cent in tax. Moreover, multi-level holding structures have to undergo a cascading effect of DDT as the exemptions for onward distribution of dividend is restricted to shareholding above 50 per cent in the downstream company.

A corporate shareholder also does not get deduction on the expenses (including interest) incurred for earning dividend as the dividend is, technically, exempt in its hands.

Foreign companies receiving dividend from Indian companies generally do not get credit in their home country for DDT paid in India, resulting in double taxation. These make long-term equity investment in companies less attractive for foreign investors and is detrimental to industrial growth.

It would be a good idea to revert to the erstwhile regime of taxing dividend income only in the hands of the shareholders. The government will continue to collect tax through the TDS mechanism.

The purpose for which DDT was introduced in 1997 is not relevant any more. The procedural issues while claiming credit/refund of TDS have been vastly mitigated through the currently used electronic mode (Form 26 AS etc) in the tax department’s portal.

Tax leakage through treaty shopping by cross-border investors is no longer as attractive because of the introduction of anti-avoidance measures as well as re-negotiation of various tax treaties. The cascading effect of taxation for multi-level distribution can also be removed through provisions such as Section 80M which grants deduction for dividend distributed from the dividend earned by the company.

The reintroduction of the earlier tax regime will, therefore, be beneficial for the investors through: (a) removal of multiple taxes (b) reduction in tax for lower income groups (c) tax benefit for foreign investors through tax treaties (d) removal of tax leakage for foreign investors through foreign tax credit in home country (e) mitigation of cascading effect in dividend taxation (f) deduction of expenses.

The change in methodology will rationalise the taxation of dividend. With higher return on investment, long-term investment in equity for industrial development will become more attractive and more money in the hands of the shareholders will lead to higher consumption.

The positive result will energise the economy in the medium and long term. Tax foregone, if any, can be offset by larger economic benefit. South Africa, which was the forerunner in the introduction of DDT (in 1993), has itself reverted to the classical system of taxation in 2012.

The investors are waiting with high expectation for this paradigm shift in the budget.

Kaushik Mukerjee is partner, tax & regulatory, and Jai Soni is associate director, tax & regulatory, at PwC India