The Fantasy Premier League is a football managers’ competition in which more than 5 million managers from around the world compete on a weekly basis by trying to pick the best hypothetical team from football players in the English Premier League. Every week, managers are allowed one transfer from their team. A common pattern observed on a weekly basis is that the most-bought player by the managers is the one who has scored a lot of points in the previous week. Although this may seem sensible at first, one would soon realise that, more often than not, this player will not deliver the same kind of exponential points in the following weeks.

Bias for past performance

Interestingly, this seemingly single-minded approach is one that these football managers have in common with a majority of investors. This behaviour is known as “hind sight investing”. Investors, just like the managers, tend to buy stocks or funds that have seen recent exponential growth, not realising that more often than not, the stock or scheme may not rally once again in the near future.

One might assume that such a behavioural bias, which may affect everyday retail investors, would not be seen in top institutional investors and management who invest heavily in think-tanks. Surprisingly, studies have shown otherwise.

Data show that institutional investors sell funds or fire managers that have underperformed the market in a two-three year horizon, replacing them with funds or managers that recently outperformed. This goes on despite studies showing the flaws in this approach and it does more harm than good. Hence, it can be said that looking at the past performance remains the most common method of investing despite the disclaimer “past performance is no guarantee of future results”.

Why does then one pay an advisory fee if many top investment professionals and millions of football fantasy managers share the same attitude towards decision making? Where is the differential and how does one generate an alpha in the long run?

Data show the pitfalls of the performance-chasing approach is often ignored due to the fear of missing out on another rally. But as Warren Buffet puts it, “If past history was all that is needed to play the game of money, the richest people would be librarians.”

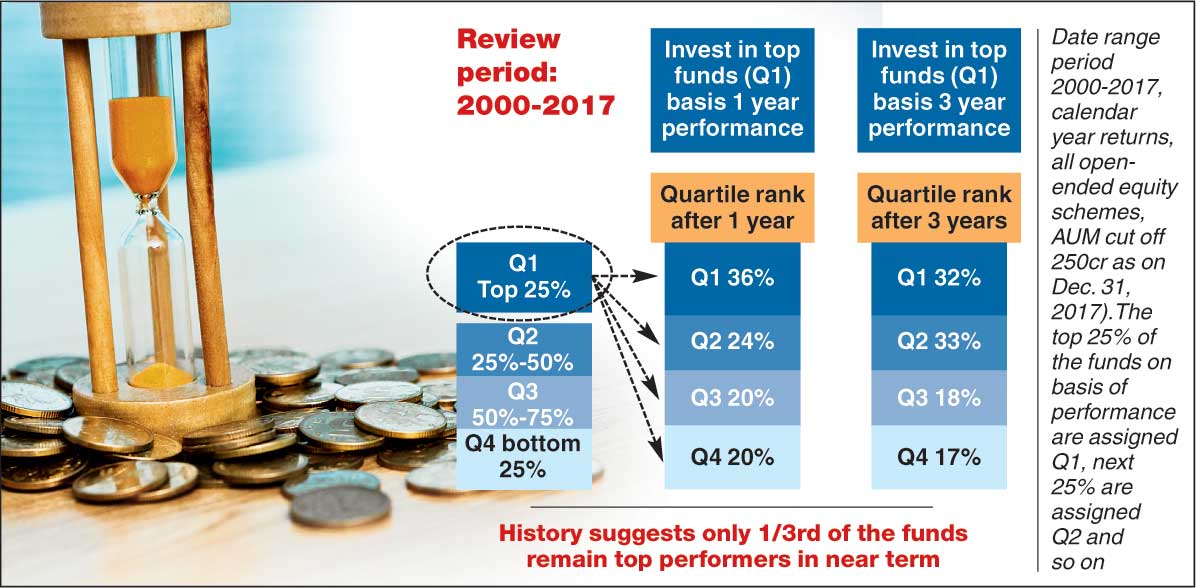

We thought it appropriate to substantiate this through some research of our own. Our study shows that there is a limited probability of getting investment decisions right that are solely based on historical data.

Let us illustrate this with some examples of the recent past. The above table comprises data of the last 17 years. Funds were ranked based solely on their performance for pre-defined time buckets. As you can see, in the 1-year bucket, 36 per cent of the funds continued to be top performers and 64 per cent could not retain their position. Similarly, in the three-year bucket, 68 per cent of the funds could not retain their position.

If we translate the above numbers in terms of probability, your chances of selecting a top performing fund based on past performance is lesser than winning a coin toss! Just like we don’t drive a car looking at the rear view mirror, investment decisions too should not be based on mere past performance. One needs to go beyond the norm of return-based analysis to arrive at investment decisions.

What to look out for

So how does one hope to generate forward looking, long-term returns?

While picking the winner of a race, one must pick the driver, not the car. The same holds true for investments wherein you lay your bet on the manager and not the fund. Let me give you our manager selection methodology as a case in point. This methodology, called the 4C framework, focuses on four factors — clarity of philosophy and style; consistency of performance; capability of manager and asset management company (AMC); and class of the manager. This involves regular review and monitoring of the manager and AMC; quantitative screening such as mapping managers’ performance across funds and AMCs every quarter; ranking the alpha generated and other variables. Various filters have been put into place to weed out inexperience, incapability and inconsistency.

Manager’s skill is key

Managers are also segregated in various investment styles. “The best long-term performers all emphasise process over outcome,” says Michael Mauboussin.

We believe that in generating sustainable long-term performance, skill plays a major role rather than luck and to assess the skills of a fund manager, it becomes pertinent to understand the consistency in his fund management process. Every manager has a different approach towards building a portfolio. Through our detailed due diligence, we aim to understand the capabilities, consistency and experience of the fund manager and substantiate their investment styles with their past and current investments.

A manager may oscillate between two extremes of investing. When a manager sticks to picking stocks which are out of favour or below their average valuations and expect these stocks to revert back, then they are demonstrating a “mean reversion” investment style. On the other hand, if the manager foresees sustainable growth in the earnings of a company and is ready to pay a premium for the stock, he belongs to the “growth style” of investing.

As different managers exhibit their strengths in different market conditions, it is viable to construct a portfolio with a long-term view and appropriate combination of investment styles which in turn would minimise duplication and over diversification.

The writer is executive vice-president and head of investments, Motilal Oswal Wealth Management Ltd